A scion of the Wurlitzer family (of jukebox/organ fame), Rudy Wurlitzer first attracted notice with the publication of the two short novels Nog (1969) and Flats (1970). Blurbed by Thomas Pynchon (“The novel of bullshit is dead”), Nog follows the peregrinations of a narrator who changes not only location but identity on a daily basis, hauling an octopus along for the ride. Flats concerns a number of equally mutable characters, named for different U.S. cities, huddled around a campfire in a hollowed-out landscape.

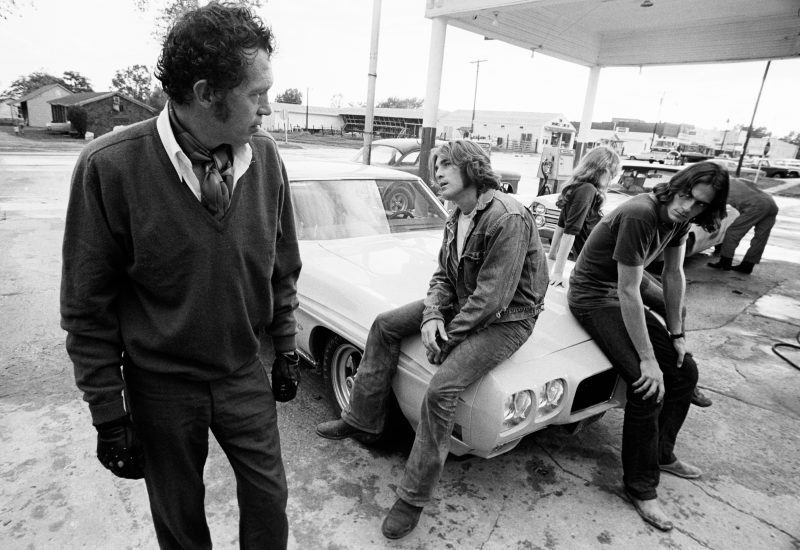

Wurlitzer fell into screenwriting around the same time, first helping Jim McBride (David Holzman’s Diary, a Breathless remake) complete the post-apocalyptic (and originally X-rated) Glen and Randa (1971), and was then tapped by director Monte Hellman, a fan of Nog, to drastically rewrite a script called Two-Lane Blacktop. An existential road movie that, as brilliantly realized by Hellman, is the logical extension of the laconic and cinematic aspects of Wurlitzer’s novels, Two-Lane features singer-songwriter James Taylor and Beach Boy Dennis Wilson alongside frequent Sam Peckinpah star Warren Oates. Heavily hyped before its release (Esquire dubbed it “the Movie of the Year” and published the screenplay in its entirety) but then dumped in theaters unceremoniously in the summer of 1971, Two-Lane’s reputation has grown over the years and has arguably transcended cult status to become a canonical ’70s film. Wurlitzer went on to script Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973) for Peckinpah, and Walker (1987) for Alex Cox; he also worked on Volker Schlöndorff’s Voyager (1991) and Bernardo Bertolucci’s Little Buddha (1993).

There has been something of a Wurlitzer revival in the last couple of years. A new novel, The Drop Edge of Yonder, based on a Western screenplay of his that made the rounds with a number of directors but was never filmed, was published in 2008 by Two Dollar Radio, which subsequently reissued Nog, Flats, and 1972’s Quake. In 2011 Drag City brought Wurlitzer’s 1984 novel, Slow Fade, back into print and released a five-CD audiobook version, read by musician and actor Will Oldham. True veterans of the post-Beat ’60s and ’70s, Wurlitzer and friend Philip Glass were early members of an informal artistic community of downtown New York transplants in Nova Scotia, alongside Robert Frank, Richard Serra, and Sam Shepard. Wurlitzer and his wife, photographer Lynn Davis, now divide their time between Cape Breton and Hudson, New York.

—Alan Licht

THE BELIEVER: In an early interview you said, “Everything...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in