CENTRAL QUESTION:

Who decides what is out of proportion?

“My name is Sørine Bentsdatter. I was born in 1684 in the village of Brønshøj. My father was a pastor, my mother died in childbirth.

“When I turned six my body decided not to grow anymore.

“I don’t care for the term ‘dwarf.’

“As a rule, I don’t care for dwarves at all.”

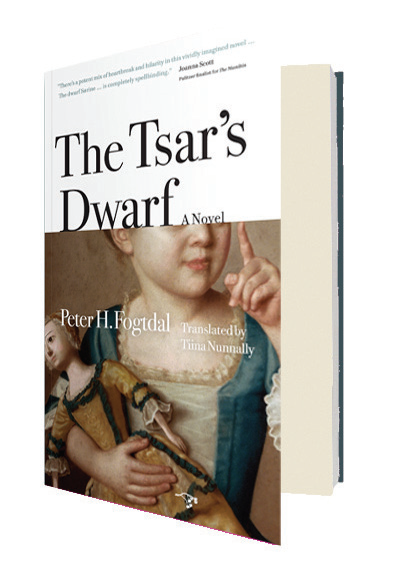

Thus begins and ends chapter one of The Tsar’s Dwarf by Peter H. Fogtdal. Fogtdal is the author of twelve novels in Danish, and The Tsar’s Dwarf is the first to be translated into English. The brisk pace, flip tone, and confounding convictions of its seventeenth-century narrator make the novel, set in the distant past, feel contemporary.

Sørine is self-loathing, but equally self-possessed. If she must endure the scrutiny and disparagement of “fine folk” (who often call out, “Look at the little turd” when she walks by), her own assessments of the fine folk are just as cutting. “His hands are fat and pink, his nails look like shiny seashells. That’s how a human being is. Loathsome and vain, with habits that increase in cruelty the more the person eats.” Physicality is never neutral in The Tsar’s Dwarf. Sørine’s misshapen bones and joints always hurt, and her height precipitates unfortunate proximities. “Once again I’m standing between the legs of servants and footmen. My nose is at the same height as forty one assholes.”

The novel opens in Copenhagen. Sørine’s current companion, Terje, her “Scoundrel,” has consumption. Sørine nurses him (an executioner’s assistant) with herbs. “But gradually I grew weary of my life. I grew tired of the eternal taunts and the smell of blood enveloping Terje.… Maybe that was why I murdered Terje. Because I couldn’t stand it any longer. Because deep down inside I am evil.” Whether Sørine actually commits this murder (and another involving her infant son) remains intriguingly unclear. Though most of her life is out of her control, the choices she does get to make never cease to haunt her.

One of the novel’s keen insights is that Sørine is more attracted to power than afraid of it. When she seeks work at the Danish court, King Frederik IV puts her inside a cake and gives her to Peter the Great. Though the charismatic Russian tsar forces her to drink too much vodka and changes her name to Surinka, she immediately loves him. The Scoundrel, King Frederik, Peter the Great, God—Sørine is drawn to forces with the power to protect her, but she is always treated like an object: given, received, regifted.

Fogtdal widens the potentially narrow first-person point...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in