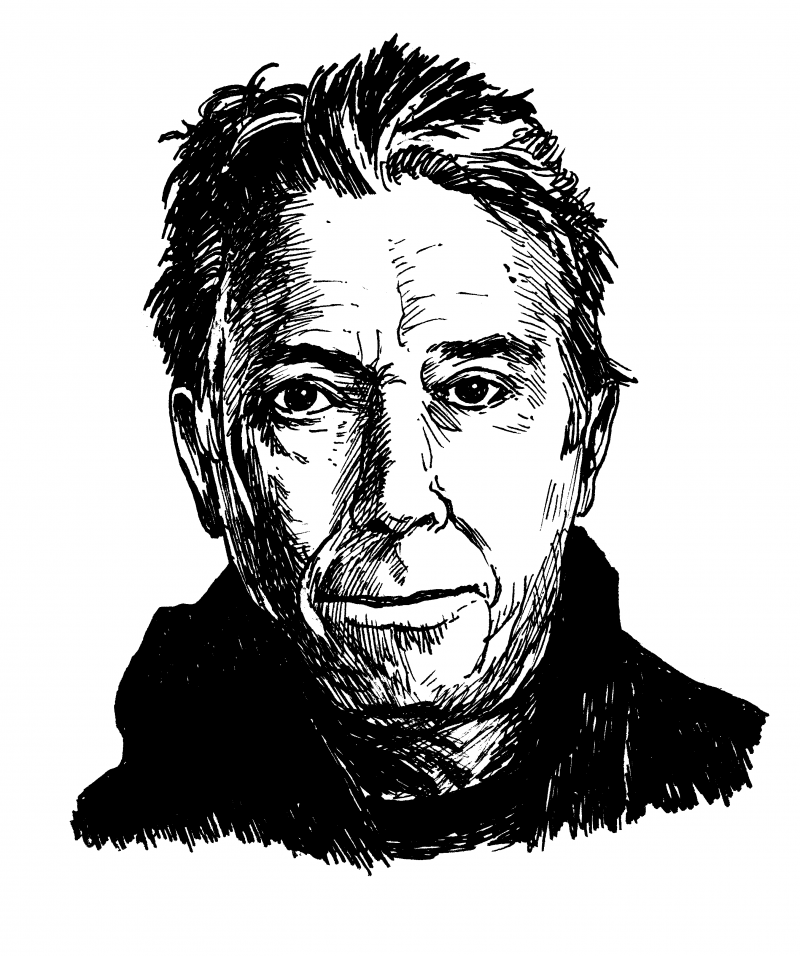

As he approaches seventy-six, John Cale is a man in a state of evolution. In the past, he tuned his instruments to a refrigerator’s hum in order to resonate on the same frequency as modern life (60 Hz). More recently, in 2014, he sent a “drone orchestra” of speakers flying through London’s Barbican Centre for a collaborative piece with “speculative architect” Liam Young. His autobiography, What’s Welsh for Zen?, includes an anecdote about decapitating a chicken onstage and chucking the parts at the audience, but he now eats mostly vegetables and a little fish. He’s a Welshman who is indelibly tied to New York’s music scene, but he now lives in Los Angeles.

The multi-instrumentalist and founding member of the Velvet Underground is an esteemed avant-garde composer and noted producer for the likes of the Stooges, LCD Soundsystem, Patti Smith, and Modern Lovers. Cale does not typically dwell—or even really think about—the past, but to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Velvet Underground, he did plan a series of shows in Liverpool, Paris, and New York. And yet Cale’s favorite album is always the next one he’s creating. To help himself segue into the future, he has been an avid early adopter and adapter of technology. There’s the Frigidaire and the drones and a revolving array of synthesizers and gadgets that create new and more-interesting sounds.

His decades-long career has been built on mind-expanding work, and he has no interest in resting on his laurels now. In fact, it seems the only time he takes a break is when he is stuck in LA’s notorious traffic. We spoke by phone after he finally made it off the freeway and into his studio, where he was working on his next album. —Melissa Locker

I. A CLOSED EVENT

THE BELIEVER: Do you go to the studio every single day? Do you treat music like a nine-to-five job?

JOHN CALE: Yes. Kinda. Not really. I mean, you go to the gym, go to the studio, go to the gym, go home, go to the gym, go to the studio, stay in the studio awhile, and then go home. It’s a good life, really a good life, yeah.

BLVR: It’s a good life, except for the gym part.

JC: You go to the gym—that’s a lot of fun.

BLVR: What do you do at the gym that’s fun?

JC: Um, punish myself. [Laughs] It’s like, you did fifty reps yesterday, let’s see, you do one hundred today. And then if you’ve done one hundred for about a week, OK, now let’s go and do two hundred. But when you come out of there, you feel like a different person; you feel like you’ve done something. It wakes you up.

BLVR: How do you find new music?

JC: Troll the web. I usually go to Asian sites. The BBC Asian program, there’s a site there, and from there you can get the names, and then you start looking further afield, and you end up, you know, looking for Malaysian hip-hop or Chinese pop. You get someone trying to create something new. I spend a lot of time going through iTunes sometimes.

BLVR: When you are trolling the internet, what captures your attention?

JC: Usually drum sounds. If you go to Asian sites, you get some gorgeous percussion sounds. And for a long time I was listening to them while Bollywood was developing, and could see some of the songs that were on these sites—hundreds of songs from films or whatever—and you heard them suddenly synthesize, and suddenly you’re noticing the structure of the song is changing, and they’re learning where the bridge should go, where the chorus should go, how can you get the bridge back where it was, and I thought, Wow, they’re learning from just listening to Western pop.

BLVR: You put out an album in 2012 that was very percussive, but also very technologically advanced. Are you inspired by technology? Do you feel like you are pushing technology?

JC: I can’t push the technology, because I’m not a scientist. I haven’t even learned code. Pretty soon a lot of people are going to be learning code. I thought Bloomberg was really spot-on in telling everybody to learn code. But I’m not going to approach it from that point of view. I approach it from a multimedia, a visual, and a musical perspective.

BLVR: You recently did a collaborative piece in London. What’s the difference between writing a song for a live performance piece and for an album?

JC: The album is a closed event. I write in the studio, I don’t sit around with a piano or a guitar and write songs. I get satisfaction out of that because I can finish the song really quickly. I can use whatever momentum I have. I’ve got to put it down, develop it, and get it as far [as I can], because the excitement of the moment of when you get that idea—you want to try and hold it and build on it and really gain strength from it. Being in the studio and writing songs like that is really the best way. It used to be that I’d try to [write songs onstage] and I would drive the band crazy and I would get frustrated. You know, I’d be yelling out changes onstage and I may have ended up with some good ideas for songs, but nobody else really got a clear idea of what it was that I was trying to do. It wasn’t very fair. But you know you’re trying to create an evening of entertainment, and it ends in this climactic form whether you like it or not, so especially when you’re on tour, you always have a song in the set that’s a free-for-all, which you allow. In the middle of a tour, it’s useful to blow off steam.

BLVR: How do you write a song? You said you think of an idea on the way to the studio. Do you just walk in and start playing?

JC: Yeah, sometimes it’s the bass, and sometimes you hear a drum pattern. More and more the songs are built around drum patterns for me. It’s a question of sitting down and trying for what is the most natural rhythm that you can think of. It’s like doing rhythmic jumping jacks: you just start saying, OK, what do I feel like playing today? And you come up with this happy-go-lucky rhythm or whatever. And before long it becomes a very serious rhythm. And it becomes heavier and heavier. But what I’ve learned from Pharrell is that you really have, like, three or four elements in the song. There have been very successful epic productions, but the hip-hop guys, they have very little going on, and it’s all in the angle of the work. I really like those hip-hop guys who have a sense of humor. There’s an artist in Texas named Chingo Bling. He has a hit called “They Can’t Deport Us All.” It’s Tex-Mex hip-hop. And Kokane has very funny stuff. Very soulful.

BLVR: You are a big fan of hip-hop and rap. Have you ever considered producing for a hip-hop artist?

JC: I know that 50 Cent and Snoop have a variety of people that work with them and the door is always open to people, and it’s very supportive of all the kids that want to come in and be part of the scene, but I’ve never been close enough to any of it to be able to really learn any more about it. I just look to the end product.

BLVR: How do you know when a song is done? How do you know when it’s good enough?

JC: You never really know. You take it as far as you can, and once you’re happy with it, usually I end up having to play it for somebody, after I know that I’m supposed to be done. There are a few people that I always say, “Hey, what do you think of this?” The minute that you know that you want this particular person to hear it, you know that you’re pretty much done—although you’re doing it to hear some feedback. It’s a smart move to know whose ears you want.

II. Repression Has Many Faces

BLVR: Do you ever lament the death of the album in the twenty-first century? Or do you feel OK with a song-based music culture?

JC: No, because I tell you: albums were constructed around singles. And sometimes you have three or four singles. For instance, the way Chingo Bling did things, he’d have a single, you have a hit, and then you build an album around it. And then you knew that people would buy the album because the single was on it. Sort of Business 101. I was always interested in albums because of how many B-sides would be on it. I always liked the B-sides because they were kind of an afterthought for people. I got a lot of interesting ideas from B-sides. At first it was kind of a fascination with what people do when their guards are down. What do they say when they’re not thinking? How musical are their ideas at that point? And you really get an idea, by adding it all up together, of what kind of personality you have.

BLVR: If the music industry in the ’60s worked the way it does now, do you think that the Velvet Underground would have sold a song to Starbucks?

JC: No. There was a certain element of sociopathic enjoyment to the Velvet Underground. I mean, we were reveling in places people didn’t want to go. And we stayed there. We didn’t go somewhere else. But then we didn’t have a machine behind us and we only lasted two albums.

BLVR: Have you heard the Pizza Underground, Macaulay Culkin’s pizza-themed Velvet Underground cover band?

JC: I’ve actually not heard them, but I’ve heard about them. And I just thought it was very funny. Macaulay Culkin’s like, milk. You could sell milk with Macaulay Culkin. You couldn’t sell “Sister Ray.” Not without a severe change of image.

BLVR: What has been your weirdest fan interaction?

JC: When we first started out, and started playing in clubs, and we could really play in clubs and see what the album was doing in terms of who came to see us, there was a trio of girls from New Jersey who came to the shows in New York. And after every show we’d all be in the dressing room, saying, “Are they here? And yep, they’re here, they’re in the corner, just standing there. It was like we were looking at Children of the Damned. These girls would stand in the corner, and we may have been interested in running around and chasing girls, but not these girls. These girls would just stand there and stare and say nothing. They’d come backstage and say hi, and just stand there. And Lou [Reed] couldn’t figure it out. I couldn’t figure it out, and Sterling [Morrison] was put off by it. He couldn’t connect it at all. At one point, Lou did sort of nod sagely and say, “It’s a meeting of the minds.” And we were all like, “Yeah, great, but what are they doing?” They just came to every show and just stood there. But repression has different faces. So we never got to know them, or understood what they were doing.

BLVR: Have you ever met someone with a John Cale tattoo?

JC: [Laughs] No.

BLVR: I bet they’re out there.

JC: Well, I hope it didn’t hurt.

III. An Officer of the Order of the British Empire

BLVR: It’s pretty well established that you and Lou had a very contentious relationship. In retrospect, do you have any idea what was with you two?

JC: Yeah, it was competition. You know, how do we achieve our goals? And we were pretty incorrigible. Like when Andy [Warhol] told us, “Don’t forget to put those swear words into those songs.” There was a frantic rush to get the ideas out there before somebody else did it. When I would go to London and want to find out what’s going on, I’d come back and I’d say, “Hey, man, we’ve gotta get going on this stuff, because they’re doing it over there.” It’s like, that awareness was just a throwback from the avant-garde, where you really make sure nobody else is doing what you’re doing. You’re dead in the water if you’re copying anybody, or you’re doing anything that closely resembles somebody else. So that was the drive.

BLVR: Do you think the creative differences and the tension helped create the sound that the Velvet Underground became known for?

JC: Yeah, it manifested itself in strange ways. It was just that we spent a year, every weekend, working on that first album. Then we went out on the road, and that’s what the second album was. So that’s kind of the trashy nature of going touring—that you really didn’t think about or work on things in the same way at all. And then you’d end up in the studio and you’d throw these ideas out and that would be it. All of a sudden anything would work as long as you could put a backbeat to it. There was no careful consideration or growth in terms of arrangement or anything else that was there in the first album. You try all of it and try to not end up hating everybody. And we didn’t have anybody looking after us, and when [a manager] did show up, Lou wanted to comanage. I mean, [the manager] was just an idiot. There was no understanding of where we’d come from and how we’d really battled our way up to that position by sticking together.

BLVR: After you left the band, you and Lou reunited to say goodbye to Andy Warhol. What was it like working together on Songs for Drella?

JC: We were very careful. You have three weeks in which to do this, and there’s a plan to do it live, and then there’s a plan to make a film of it, and then you can take it anywhere all over the world. I thought about doing a requiem for Andy, and even the orchestral stuff and all that, and then there was a conversation about, well, what would Lou be a part of? And then Lou and I had a conversation, and it became, suddenly, much more important to expose what the two of us had, by creating a show with just two people onstage, to let everyone see our story. I thought that was more important—almost more important than the music. But we got it done. There was an attitude of: Yes, this is what we do, and we are good at it, and we will do it.

BLVR: And what was your relationship like with Andy?

JC: Oh, great. You know, he had his group of people, he was very busy doing a lot of stuff, and it was all very, very much in the limelight. I was really appalled when I found out that Lou had fired Andy. It came right out of the blue. I asked Sterling, “Did you know this was being discussed?” He said no. If the conversation was about music, it was always happening with Lou. I never spoke to Andy about anything except business matters, band things. And it was [director] Paul Morrissey who was kind of running the show anyway. But Andy was always very generous to me. He made a couple of album covers.

BLVR: Do you have a favorite Velvet Underground song?

JC: Not anymore.

BLVR: Not anymore? What happened? You can’t listen to them anymore?

JC: I dunno. I just can’t. I can’t find that sensibility anywhere else. It really depresses me.

BLVR: You were appointed an officer of the order of the British Empire, but you don’t get to be a “sir.” When you see people like Sir Paul McCartney, does that annoy you?

JC: Oh, no. You’re grateful for being afforded some recognition. I’m not that kind of a climber. I could have said no. They offer you the option: do you want it or don’t you? It was really about Wales and helping Wales out. So I was glad to do that.

BLVR: Do you ever wear your medals?

JC: No.