I was underdressed for Lisbon. The men wore suits. Corduroy is the fabric of choice. Portuguese corduroy comes in shades of brown. There is tan, beige, sesame, and burnt umber. The suits look toasted. Or caramelized. They seem almost perishable.

In a tonal city of edible colors, I was not blending in. I caught anxious glimpses of myself in store-window reflections. My primary-colored T-shirts might as well have been inmate-orange jumpsuits. I was Waldo.

It was mid-December, off and on rain. Streets flowed down toward the bay and the shop-heavy Baixa district, where the corduroy was sold. The rain would start and I would pull a crumpled blue slicker from my messenger bag and try to pull it over my head as I walked. Well-dressed Lisboans in fedoras and carrying umbrellas looked on in either bemusement or disapproval; it was hard to tell which.

I needed to find myself one of those corduroy suits. It would be something to take home. It would not decompose on some forgotten shelf or stand anonymously on a crowded mantle. No, I would wear my souvenir. I would become it.

Finding the right suit was not simple. I sat at coffee shops, snacking on unpronounceable confections and nabbing glances through full-length windows as suit after corduroy suit strolled by. You can eat all day in Lisbon. Rows of parallel pastries, hued and sorted to match the passing fabric, lined the café windows. Baked custard pies. Mini-flans. Tiny cakes that weren’t actually cake. Each comes loosely wrapped in a translucent sheet of off-white waxed paper. A bell hooked to the door, American diner–style, chimes as people come and go. A dark-haired woman in a cream overcoat, unfolding her espresso umbrella, smiles to herself as she rises to leave.

I was lost on the city’s checkerboard sidewalks. These limestone cubes are not crowned, as are cobblestones in most cities. They are fit together, and, except for those places where time and small movements of the earth have disturbed them, they form a flush mosaic of charcoal and plaque squares riding the waves of Lisbon’s gentle hills.

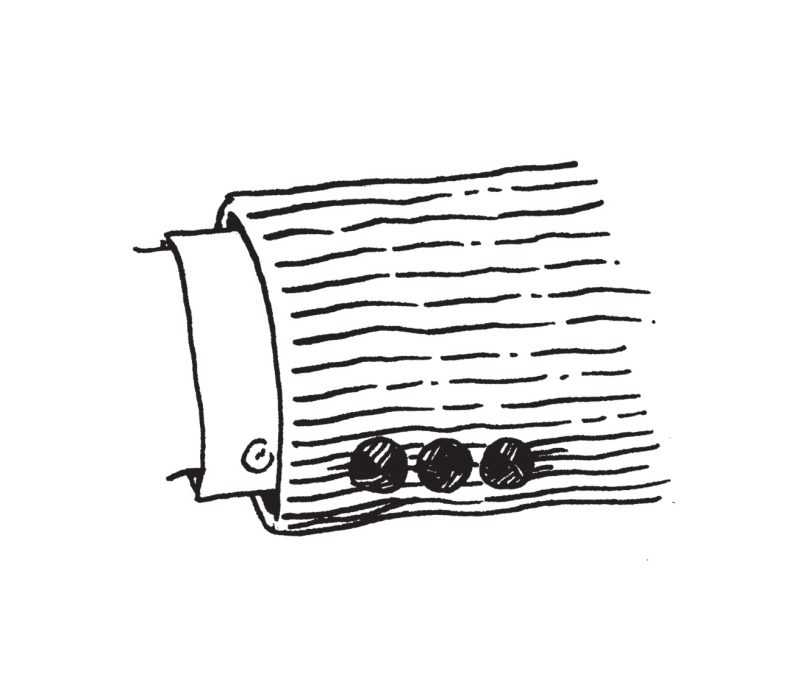

I popped into shop after shop trying on suits. Nothing fit. They looked absurd on me. I am not a big American, but in these cuts I was all wrists and ankles. Sleeves were too brief. Inseams too high. Dapper, short men worked in these stores.Their dark hair was parted and their brown clothing hung effortlessly on their five-foot, six-inch frames. Their lives brimmed with corduroy, I thought. In their homes: dish towels and pot holders, corduroy wallpaper and bed linens.

The shopmen and tailors were attentive and helpful. With each ill-fitting suit, they shared my growing sadness. I again faced the triptych mirror and found a silent chorus of down-turned mouths and shaking heads looking on gravely from behind my padded shoulders.

Empty-handed, I returned to the street. The sun dropping, shops were closing and the streets were filling with more and more of the relaxed and the beige. Did they know each other? Pedestrians who seemed strangers would spontaneously assemble, exchange animated stories, and laugh. Then they would part, one walking under repeating stone arches, another alongside a peeling saffron facade topped by wide-waled rows of terra-cotta shingles. Folds of sunlit fabric fell around their striding legs. I thought of Magritte’s rat-race city, countless men in the same suit. But in Lisbon the uniform is the color of sand, and no two men walked in the same direction.

Blending in wasn’t going to work. Having the city in my pocket,wearing the city,was a conceit too far gone. I knew this, but held on still. A small and powerful instinct to possess a place drove me to irrational behavior. On my last day in the city, with few hours to spare, I settled on a sport coat, the color of a spot of coffee cooling in a spoon. Part of the whole now in my clutch, I vowed to return and find its better half.