The state-run Fábrica de Muñecas Yoruba at Carretera de Gibara #260 in Holguín is one of Cuba’s largest doll factories. I would venture the reason this factory qualifies as a special point of interest is that the city’s primary features are dust and heat and blind streets without traffic lights or stop signs. Nevertheless, with a couple of hours to kill before our bus connection, and having exhausted the mechanical-organ factory down the street, my boyfriend and I decided to give it a whirl. “They make the dolls by hand,” the caretaker at the organ place explained with trace excitement, “you can see everything.”

We hesitated outside, maybe because it looked so new and improbably glassy. Then the door flew open and a matronly woman popped out; with a volatile swirling of skirts and hands she swept us briskly in. I was busy wondering about her need for a wool sweater, scarf, shirt, and long wool skirt in hundred-degree weather when I noticed we were in the factory gift shop, where an astonishing two hundred or more dolls were engaged in staring at us. Dozens of prim white faces gazed out with shining black eyes and pert red mouths, while carmine and ebony lace-edged tulle spilled in rich lava flows over six large shelves.

Except for the variation in dress (shiny red or black), the dolls were identical: no diversity of size or age or skin shade. Although they claimed to be Yoruban, I couldn’t see anything African about the dolls; if anything, their old-fashioned, coquettish dresses and immaculate stillness put one in mind of languid Spanish ladies perched on the veranda of some ageless sugar plantation adrift in time.

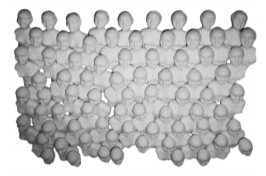

We hedged away through the passage into the classroom-sized main part of the factory, where a young woman, about sixteen, stopped chewing her tiny whitebread sandwich and watched us. In the oceanic calm of lunch hour, we wandered through an airy room painted tranquil robin’s-egg blue. Beyond the plate-glass window, clouds of dust revolved about themselves and passed down the empty street, supposedly one of Holguín’s main drags. The stillness was so intense that looking at the seven or so sets of pliers, hammers, and wire laid haphazardly on desks you had the sense that you were somehow in a Pompeii where everyone had managed to escape. Against the far wall, stacks of cardboard boxes massed on shelves. Lower down, we could see inside the boxes: heaps of arms, legs, torsos, necks, heads entirely bone-white, heads painted only with poppy-seed eyes and flyspeck nostrils, heads complete with puckered scarlet mouths.Wire. Hair.The matronly woman came up eagerly from behind and showed us how everything assembled by presenting dolls in various half-formed...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in