Impetus

My CDs are kept on a shelf. When I think, “I would like to listen to some music,” I go to that shelf and examine them, consider them. I look at the spines and think, “I could listen to that… or that. That’s pretty good… I haven’t listened to that in awhile.” I think lots of things. My last thought, however, is invariably the same: “Yes, but why would I listen to that when I could listen to Souled American?” And then I do. I walk across my apartment—which is to say, I take approximately four steps—and consider a refined selection: Fe, Flubber, Around the Horn, Sonny, Frozen, and Notes Campfire.

These albums are kept isolated from all the rest, in a neat, brief row above my stereo. I stand before them and thus begins a new selection process. Using an approximate calculus that accounts for current mood and desired mood,

I pick an album. Whatever I decide, I decide this: to listen to Souled American. Since last August—when my friend Jeremy graciously bought me used copies of the first four—I have listened almost exclusively to these six albums. I do not mean that I have listened to them often or a lot. I mean this: when I listen to music, I listen to Souled American. I mean that I spend multiple hours per day listening, over and over again, to these albums.

And the thing is, I’m not even sure that I like them.

Expert

The music Souled American plays is not particularly pleasurable. As John Darnielle of the Mountain Goats wrote about first hearing the first song from their second album, “It was kind of annoying, but it was also hypnotic.” The music certainly isn’t uplifting. There is, again in Darnielle’s words, “an almost cosmic sadness to it.” The music isn’t technically impressive. Darnielle calls it “all huge droning suspended upright bass notes and keening monosyllables, decorated by heavily reverbed twanging guitars.” The music will not make you dance or sing along or do some stupid air-guitar thing. It fulfills music’s simplest function: it makes you listen—compulsively and tirelessly, spellbound and uncertain.

Evidentiary

The history of Souled American is one of loss, of disappearance. Originally, when they formed in 1986, Souled American had four members. Chris Grigoroff sang and played guitar. Joe Adducci played bass and sang. They both wrote songs. Scott Tuma, he played guitar, too, but quit in 1996, just before their most recent album came out. Jamey Barnard played the drums, if sparingly, but he left the band after their third album in order to focus on art and a family.

Grigoroff, Adducci, Tuma, and Barnard released three albums in three years: Fe in 1988, Flubber in 1989, and Around the Horn in 1990. Barnard left the band. Sonny, the fourth, came out in 1992, but mostly overseas. All four went out of print; all four have been reissued by tUMULt in two volumes as Framed. The band made two more albums with a man named Scott Lucas occasionally performing that drum function. Frozen came out in 1994. Just before Notes Campfire appeared in 1997, Tuma left the band. Both Frozen and Notes Campfire are now out of print. In 1999, Adducci and Grigoroff moved to Charleston, Illinois to begin work on a new album, an album that, after nine years of work, is still unfinished. Since the move, they’ve released two songs: one in 2002, on a Kris Kristofferson tribute album; the other in 2006, on a CD that accompanied the fourth issue of Yeti.

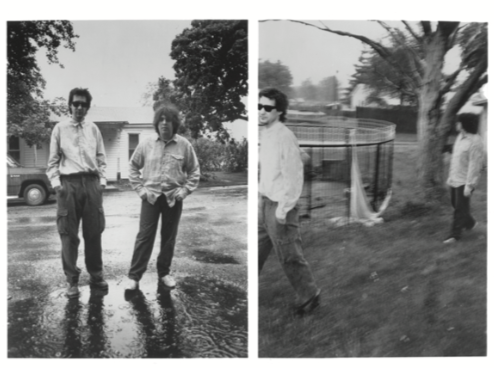

Diminished now to two, Souled American still exists. Here is the evidence: last summer they played a pair of shows. They played once at the Swing Station in La Porte, Colorado, then at the Beartree Tavern in Centennial, Wyoming. It was not a tour, nor the conventional and convenient hometown shows that dwindling bands sometimes still sneak out to play. No, it was a long drive, one that must have exceeded at least a day in each direction, from their home, which they share, outside Charleston. It was a long drive to nearly nowhere, to tiny towns in depopulated parts of Western states.

Imaginative qualities of an actual thing

When they arrived out there, I imagine they played the kind of set for which they are infamous. Imagine two men with long hair and dark sunglasses seated on a dim stage. One, tall and thin, plays a spidery and halting guitar. The other, less tall and less thin, plays a lurching, booming bass at a torpid pace. Together and apart, they lean into microphones and sing grim words with stretched and stricken voices. By now, people have begun to leave. The band is quiet in the wide space between songs, except when requesting that someone make the dim room dimmer. They are still wearing sunglasses. More people shuffle off, leave the Swing Station or Beartree Tavern, and head out into the La Porte or Centennial night. The band doesn’t seem to notice. When the audience brings chairs out from a corner stack and sits before the stage, Grigoroff says, as Rolling Stone quoted him saying in 1999 under similar circumstances, “We got a living-room thing goin’ here. I can dig that.”

Approximate depth of the bass sound

It’s a matter of debate: How deep underwater, exactly, does the bass sound?

One writer, a Julie of Tiny Mix Tapes, approximates that Adducci’s bass “was recorded underwater from three rooms away.” Jeff Stark, writing for the SF Weekly, writes that the bass “blubbers as if separated from the rest of the music by five fathoms of river water.” Andee Connors, founder of tUMULt, the record label that rereleased their first four albums, is less specific: he simply says that the bass sounds “bubbly and underwater.” He’s right: a precise measurement is irrelevant. The bass is deep and distant. Deep and distant, but placed at the top of the mix. It’s a sound made by a six-string played with an idiosyncratic two-finger method.

When combined with the country-folk guitar sound, the result is something like listening to the Anthology of American Folk Music on the stereo in your room, while the guy in the apartment above blasts reggae—the bass seeps through the floor, matches the tempo exactly, the way car turn signals sometimes accidentally align themselves, blink at the same beat.

This is the bass. Or, this was the bass. Now that only two players remain, the bass is changing.

On the loss of instruments

The bass was not the first instrument to fade away. The drums, too, where’d they go? On the first three albums they were there, if not often. Barnard kept a solid beat on one song, absented himself on the next, returned to occasionally strike a cymbal or brush a snare. Plays, leaves, comes back quieter. Then, on Sonny, Frozen, and Notes Campfire, he’s gone for good. He does not return, though a hired hand, Scott Lucas, will sometimes play even more scarcely. Now, the drums are entirely gone. Without them, there’s still a natural, simple rhythm in these songs. Your foot (metonymized as a toe) will tap (very slowly) to it. The absence of anything marking the beat makes these songs, already so slight, tenuous. According to the cliché, drums “lay the foundation.” In which case, these songs are shacks. Shambling, precarious, maybe, but exactly enough—four walls and a roof. They give you shelter, but never comfort.

The guitars, they are still here. There are two of them. According to Grigoroff, Adducci, when not playing bass, will play the guitar Tuma left behind. Together, they play frail, spidery sounds. They pick strings and allow them to resonate. They bend strings to prolong and warp the notes. Sometimes, especially on the early albums, they strum their guitars. Sometimes, especially on the later albums, they do not. Still, somehow, the sound is, if strained, propulsive. It’s an old sound redolent of the days when the guitar, unamplified, made all the music—kept the beat, played the melody, set the tone—but did it all in the background, allowed the voice to come out on top and say what had to be said.

Not a simile

The voice. Or rather, the voices. There are two of them, both serious and strained. One is higher. One is lower. Both are shaky and intent. They are sometimes clear and forceful, other times so quiet they cannot be deciphered. They sing like they have something vital to say but aren’t sure they should be saying it. Your brain cannot quite decipher what the low and concerned voices are singing.

Says Chris Grigoroff, “When Joe and I got together, we always wanted to have some essence of country music, because that’s what we were. We were both kinda folkies in a weird way, without really knowing it. We both loved reggae and R&B, so we just hybrided it into that.”

The result is this: their music sounds like Bob Marley and Hank Williams stoned on morphine, playing their saddest songs together. That is not a poorly mixed simile: it’s the subject of a Souled American song. It is called “Marleyphine Hank.” The lyrics, in their entirety, are “Marleyphine Hank,” and they are repeated six times by a chorus of voices. It sounds like an incantation. It is a sad song.

The songs they play

They cover songs by John Prine, John Fahey, George Jones and Hal Bynum, Hank Williams, Merle Travis, the Louvin Brothers, Little Feat, and many others besides. They play songs by Vicki Adducci, the bassist’s mother—and these are some of the most haunting songs of all. Mostly, though, they play songs written by themselves.

The way they play them

In 1923, Fiddlin’ John Carson made what is generally recognized as the first recording of a country song. Hank Williams was born that year, as well. Between then and 1953, the year Hank died, a plethora of styles and a diversity of sounds were refined into a single, recognizable, marketable form and formula called Country Music. Since then, the country has changed dramatically, yet Country Music has not. It has ossified, been formalized and routinized.

As Richard A. Peterson argues in Creating Country Music, “Authenticity and originality had been fully fabricated by 1953; the audience had been identified, and the country-music industry fully institutionalized.”

Today, both alt-country and Nashvillian pop-country invoke the sound—and attempt the sentiment—of this standard country music by adding a little twang here, a little pedal steel over there, a properly accented vocalist right in the middle, some fiddle in the back. These bands take a pop or rock song and “make it country” by adorning it with a cowboy hat and some distressed boots. They never quite get where they want to go, because they want to go backward, back to the sentiment of a Country Song. They will never get there because the destination—the country—is gone (or it never existed).

Souled American aren’t trying to go back to anything. They’re forging forward, foraging for the sound of a diminished America. The Souled American catalog illustrates the process by which one arrives at a kind of country music that has never been played before.

They make a new kind of country music for a new kind of country. There is a new America and it makes a certain sound—one that is spare and despairing. Souled American makes this sound, this tired wheeze our nation makes. Souled American, obscure and secluded in small town U.S.A., knows this sound and they play it. How did they find it? They found it by inverting the process by which most bands attempt to do so: via subtraction rather than addition.

Over two decades sloughing off instruments and decelerating the rhythm, the twang has been protracted into bent notes. The pedal steel has been replaced by shards of incidental sound. With the adornments gone, there is space for sentiment to spread out. You can hear this happen.

Hear this happen

Start with their first album, with the third song. “Soldier’s Joy” is a traditional: they play it with harmonica, shuffling drums, bubbly bass, clean guitar, clear vocals. They play it the way an alt-country band would: as a full band, with the speed and restlessness of rock and roll and the twang and hustle of a country band. Go from there to their version of “Please Don’t Tell Me How the Story Ends” from the 2002 album Nothing Left to Lose: A Tribute to Kris Kristofferson. When you arrive there, you’ll find a fuzzed-out guitar and some loose piano keys chugging sluggish, steady, with an occasional hitch. Chugging like a derelict steam engine up an Appalachian incline.

They’re still going up there, but now they know what they’ll really find: not quaint cabins filled with Foxfire personalities playing mandolins and fiddles, slaughtering hogs, and building their simple homes from felled trees and oral instruction. No, that’s gone: instead, they’ll find fireworks stores and satellite dishes and dogs lingering at trailer-park Dumpsters and supermarket shopping carts abandoned on the shoulders of state roads.

And Souled American is still going up there—unhurried, reluctant, like they don’t ever want to arrive. They’re going up there and they’re bringing field recordings down for all of us to hear.

Words of glass

On “Born(free)” from Notes Campfire, someone, it’s impossible to discern who, sings, “There’s no love / there’s no love at all / no love at all / there’s no love / no love at all / no love / there’s no love in my house / no kiss from the morning time / it’s all dark in my house / I don’t understand / there’s no love on my street / no way from the corner man / it’s all dark on my street / and I don’t understand / no / is why I’m so afraid that / all these words are made of glass / and this feeling won’t pass.”

“All these words” may be “made of glass,” but a window becomes a mirror when it gets dark outside. “It’s all dark on my street” and these words, they reflect: they show us something about ourselves.

The sound is stark, the lyrics dark. Still, it amounts not to bathos but beauty. Beauty is truth and truth beauty and all that. As they sing on “Full Picture,” “Not conveyin’ what is real / is bound to cause you shame.”

Pillows of air

Lawrence Weschler has described “those moments of hushed astonishment or absorption when a pillow of air seems to lodge itself in your mouth and you suddenly notice that you haven’t taken a breath in a good half minute.… The sort of moment, that is, that has proven increasingly fugitive in the temporal frenzy that has come to characterize the increasingly peg-driven, niche-slotted, attention-squeezed, sound-bit media environment of recent years.” He is speaking “of a kind of death of the soul.” “Slow down,” he admonishes, “give us leave just to look and to see and to admire and to be amazed, and then to rest for a few moments, to lounge in all that splendor.”

His antidote appeared in a magazine he started. Called Omnivore, it lasted exactly one issue. It was a prototype lost in the very frenzy it lamented—the same blind hustle that has left Souled American behind, as well.

This frenzy, it is a sprint without a finish. Some have stopped running. There they sit, quiet and unnoticed, on the infield. They wander off, not sure where they’re going. You can find them where they linger, on front porches and stoops, sidewalks and underpasses. You will find these figures all across America. They live in a country parallel to, and distinct from, the primary one. It’s dark on these streets. There’s no love in these houses. For what has been the change in America, if not the loss of love? The soul has been sold. We have been souled. They are not called Souled American for nothing.

A generality

What matters less are the notes played and sung; what matters more is the ability of those notes to evoke. There is something impressive about technical ability, but there is nothing inherently satisfying about it. Think Yngwie Malmsteen; think the Ramones. The result is reverence for the authentic. Authenticity makes possible the evocation of a world unlike our own. We must trust the teller to believe the tale.

An example

This, I think, is why Harry Smith included so much information in the handbook that accompanied the Anthology of American Folk Music. This is why he writes of Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “Rabbit Foot Blues,” “The first authentic recordings of Texas folk songs were made by this artist in the rug department of a Dallas store in 1924.” This is why he tells us about the alternate versions of “Bob Lee Junior Blues” and even provides their record numbers (Vocalion 1193 and Victor 38020). This is why he includes illustrations of the banjo finger positions for a C, F, and G-seventh.

It is not because any of this inherently matters, but because these details are the scaffolding that supports the world Smith is making. We read these notes while we listen to the album, and we build in our brain a place for these songs to be played. In this way, the songs become historically authentic.

But if some information allows you to believe the teller, too much makes you distrust him or her. Authenticity is always a construction, a fabrication. It is only convincing when we are allowed to build it to some degree ourselves, when we are allowed to spackle over the inevitable gaps and inconsistencies with our imagination. Urgent telling gives way to the ironic impossibility of so doing. As David Foster Wallace wrote, “Today’s irony ends up saying: ‘How totally banal of you to ask what I really mean.’” And so, when someone, finally, at long last, tells you what they do really mean, it’s hard not to listen.

A contingency

The musicians Harry Smith anthologized lived at a time when information traveled slow and cumbersome. Their near anonymity, more than likely, was not a choice. After all, among the multitudes of men and women playing and singing in the mountains of Appalachia, on the plantations along the Mississippi, and elsewhere in early-twentieth-century America, only men like Furry Lewis and groups like Cannon’s Jug Stompers came out and sought recording sessions. These people sought access to a wider audience, whether or not they found one.

Today, everyone has access, more or less, to the same means of disseminating their songs. Obscurity is now a choice, and Souled American has chosen it: they are a band without a record label; they are a band—God help them—without a MySpace page. They do have a website, alas, but it contains only cryptic text that still announces those shows they did last year and a linked email address that does not work. The members of Souled American do not have email. With limited access1 and little information, we are left only with the songs.

Together, the reduction of Souled American’s sound—its radically spare simplicity—and the absence of information, their total lack of publicity or promotion, their near nonexistence outside of their songs, leave us hanging on every note and syllable. We are humans: we want to know who they are and what they mean. We are left to decipher and discern. We wait in the ever-widening sonic space for the next hint or clue. We anticipate. We listen. We wonder. We need to hear what comes next. In our fast and excessive world, it’s languor and dolor, of all things, that create urgency.

Corroboration

The result is this: a limited but devoted following. There is an inverse relationship between the size of a crowd and its stridency, and Souled American’s minor, marginal fan base compensates for the low number of voices with the loudness of each.

In 1997, on the occasion of the release of the then-new album Notes Campfire, writer Camden Joy initiated a project to create and paste around New York City laudatory posters about the band. Though called “50 Posters about Souled American,” the contributors, which included Jonathan Lethem, S. E. Barnet, Jay Ruttenberg, and Janet Steen, made sixty-one of them, each numbered, each unsigned. The posters show cautious hope about a possible rejuvenation of the band’s career—and yet, this possibility is tempered by worry about the band’s gradual disappearing act.

The thirteenth poster reads:

Imagine a band shrinking as it grows, rather than expanding; shrinking in terms of ambition, output, melodies, band members, production aesthetic… Six albums into it, Souled American seem closeted and apologetic, beautiful and lost, hermetic, gone. In typical fashion, their title for this new album—Notes Campfire—was also the title of the first song on their very first CD. It seems appropriate that this be the comeback moment, or the final moment, one or the other, that this is a career reeling in on itself, circling close, mouth gaping for le fin.

But it was not the end. Souled American are disappearing, but they have not disappeared. Not quite. Not yet.

In the end was the beginning

Novelists sometimes say that all of their work comprises a single book. In this sense, Souled American’s six albums make a single song. It is a song. It is a dirge. It is a requiem. It is a song the way a symphony is: one with movements and changes that are girded by a recurring, insistent theme. The theme is a lament. The lament is for loving. It is a song that begins with their first song, which is called “Notes Campfire,” and ends, for now, with their last album, which is also called Notes Campfire.

They begin and end the same way. The beginning is the end; the end the beginning. There has been nine years of near-silence; someday, presumably, there will be another album, a new ending, a new silence, a new ending, etc. The ending, though, will always be the same: love is teleological; it always ends in loneliness.

“Notes Campfire,” the very first song of sixty-six, ends with a mock assessment of the band that plays it: “I know what the band plays / I know what the band fes2 / I know what the band does / I know what the band needs / I know just what they do.” This statement—so directly about the band itself—is declared so it can be overturned. And this is Souled American’s project over the course of this six-album song: to show you what they play and do, to tell you what they feel and need, only to take it all back, turn it over, change it around, and give it to you, altered, again.

That doomed inevitability resurfaces on the first song of the album Notes Campfire, “Before Tonight”: “a song before a voice / a chance before a choice / a lamp before a light / stuck with today before tonight.”

The circuitousness and sentiment of inexorableness that defines both the sound and structure of the long Souled American song is echoed in the words of the superb Irish writer Flann O’Brien, author of The Third Policeman: “We endlessly dramatise what we are pleased to call ‘life.’ And, in point of fact, the element of theatre is there, there is a… struggle, there is… a—given a great man, of course—there is a tragedy: above all, there is dramatic irony.” We want a choice and act as though there is one—but there is not. There is only the distance between what we believe we actively can choose and what will inevitably happen. There is “a chance before a choice”; but we’re “stuck with today before tonight.”

A country of wonder

Souled American exists in a space between—between country and rock, reggae and folk, love and loss, obscurity and recognition, tradition and innovation, frenzy and fatigue, obfuscation and candor, between regret and possibility, and between albums and years. They have been lost in the gap, but in the fissure they have found room enough for wonder. Wonder exists in the distance between the notes, in the breach between our bare knowledge and what their songs suggest, in the expanse between the lyrics we can decipher and those we cannot parse.

It may sound dark and dolorous from a distance, but Souled America is a country of wonder.

Coda: lyrics to a song called “Flat”

One note wonder / one note wise / one note certain / one note side / side / one note leader / one note lead / one note savior / one note said / one note trumpet / one note bend / one note presence / one note sound / be on your way / beyond your truth / beyond your love / beyond what makes you / do / beyond you / sooner or later / flat / sooner or later / flat