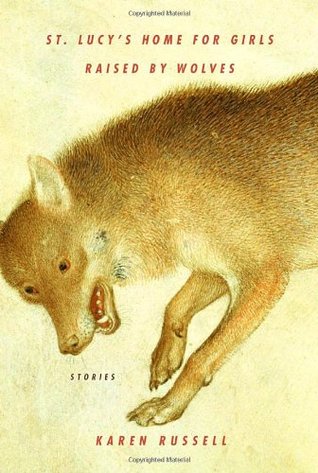

Narrated by strange, quiet children and nestled deep in the mystique of the Everglades, Karen Russell’s stories are unnerving, darkly funny, and immensely enjoyable. Their standard recipe takes a common coming-of-age theme—“my parents are lunatics,” “death is part of life,” “growing up is hard”—folds it into a surreal situation—“my dad is a Minotaur,” “I am trapped in a giant conch shell with a janitor,” “my 14 sisters and I were raised by werewolves and now nuns are trying to prepare us for life in polite society”—and tops it off with superb, efficient sentences. Mix well and you’ve got one of the strongest debuts in recent memory.

The grown-ups in these ten stories, werewolves or otherwise, are usually bumbling doofuses, hopeless introverts, or worse. They loaf around, drink too much, and search for new ways to fornicate, generally acting like extras awaiting a part in a George Saunders story. Given such disheartening role models, it’s no wonder Russell’s young characters are a detached and prematurely world-weary bunch. They speak with wry vocabulary twists and an unlikely, sophisticated humor. “Makeup is forbidden in our household, but my sisters have slathered their lips with beeswax so that each syllable emerges at a blinding wattage.”

Despite their articulate commentary, these kids aren’t precocious know-it-alls. They see the world as a disorienting and foreign place. They engage it with naïve and unprejudiced curiosity. A Minotaur dad is no more awe-inspiring than one who drives the Zamboni at the rec center; schools of glowing ghost fish are no more terrifying than a sister’s glimmering, waxy lips. Moving skillfully between the banal and the extraordinary—a dingy dining room one minute, secret underwater caves the next—Russell blurs the boundaries between the real and the surreal until we become hyperaware and suspicious of every detail. It’s an effect that lasts even after you set the book down. Your apartment vibrates weirdly. Your wife seems like a stranger.

Wisely, Russell never confuses childhood curiosity with innate intelligence, or innocence with moral purity, attributes often bestowed upon literary youth. Take Ollie, from one of the collection’s strongest stories,“The Star-Gazer’s Log of Summer-Time Crime.” Seeking to impress a bully, he spends the summer verbally abusing his sister, ignoring his depressed father, exploiting a retarded man, and luring endangered baby sea turtles into a burlap sack. He’s an innocent kid, and even quite likable, but at the end of the day, he’s a child at the mercy of childish insecurities, childish...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in