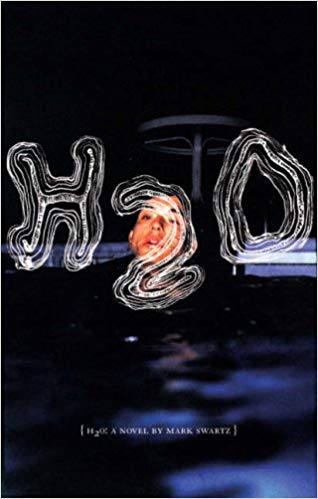

Hayden Shivers, the narrator of Mark Swartz’s H2O, designs water filtration systems for a living—not a bad job in 2020, when a worldwide shortage of clean and potable water sets the stage for global corporate opportunism that makes today’s oil market look like a church bake sale. Shivers’ star rises when he discovers a mysterious fungus from Malta that somehow secretes more water than it absorbs. Trying to understand how it works is hard enough, but figuring out what his corporate masters plan to do with it forces Shivers to choose between the temptations of personal gain and the less remunerative virtues of the truth. Yes, this is the case of the Maltese Fungus.

Swartz’s Chicago doesn’t offer a very pretty view of the future. Thanks to the outsourcing of public services, Shivers’ employer, mega-corporation Drixa, controls the water supply for Chicago, now a city-state that delivers water across the Midwest. But maybe this is a hopeful dystopia. Drixa is, after all, kind to those who protest its water products—it even pays for their flyers. And once Shivers relinquishes ownership of his breakthrough discovery, he’ll become Chief Engineer. As he tries to figure out the fungus, though, he finds it harder to ignore how the company, protesters, and press direct the flow of both water and information. The more deeply he’s involved in Drixa’s preparations to market its new product, “H2O,” the more uncertain Shivers becomes about Drixa’s intentions—and, ultimately, about his own ability to fish out, from the company’s flood of misinformation, whatever truths might remain.

Shivers’ voice is equal parts bravado and self-recrimination, mimicking film noir private dicks, reluctant adventurers, and generations of their hard-boiled progeny. The classic elements of their stories are all here—including the charming villain (Drixa’s director, Lionel Dawson), and a couple of femmes fatales (craven careerist Miyumi Park and activist Aqua Bella). Shivers stumbles on the enigmatic fungus—and its attendant environmental and ethical problems—just as haplessly as the cinema shamus who can’t resist the lady who walks in with cash, no appointment, and the wrong kind of case.

Detective work seems to come as naturally as filtration design to Shivers, a lifelong film fanatic.The heroes of the movies he loves separate the true from the false,the reliable from the unreliable.The depth of Shivers’ detective identification is clear, especially in his use of similes; they echo his screen idols’ exaggerated reaches for novelty, which always suggest...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in