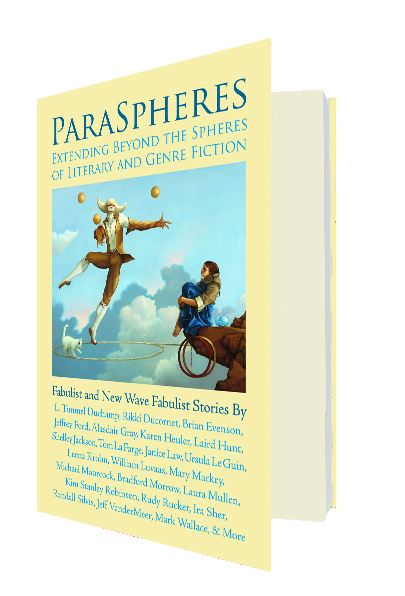

The anthologist’s job can be pretty thankless. However inclusive you are, however clearly you mark the boundaries of your mission, it’s impossible to satisfy everyone. But to compensate for the inevitable and variable ingratitude of readers, anthologists have tremendous power to shape how others understand their subjects. In Omnidawn’s new fiction anthology, ParaSpheres, Rusty Morrison and Ken Keegan attempt to establish a category “beyond” the “literary” and “genre” labels publishers use to stamp work as serious or trivial. To succeed, they must first argue that genre fiction, particularly that labeled “fantasy” or “science fiction,” can offer more than mere escape.

As has been argued by others in recent years, “genre,” in this sense, is less descriptive than inclusively dismissive. And using the word literary to denote worthiness is no more helpful than describing a thought as “deep.” Neither term says much about what a text does—or how it does it. But Keegan’s ongoing assertion is that the “literary” text, with its “narrative realism,” enjoys a special relationship to reality and overlooks many prose styles and orientations that already seem to enjoy “literary” status. He makes room in his new category for works that “offer variations on the patterns of thinking—of narrating reality—that are most commonly mass-produced.” But by this standard, most modernist writing isn’t “literary.” So what do we recognize in Virginia Woolf’s novels that we don’t see in Star Trek novelizations?

Searching for a satisfactory term to describe work the “genre” label has led readers to underestimate, Keegan and Morrison turn to “fabulist” and “new wave fabulist.” The first, Keegan notes, has an association with magical realism that gives it some credibility, but doesn’t describe stories that take place in less ordinary settings. On the other hand, the latter term, introduced in 2002 by Conjunctions magazine, can describe those stories as well as those that combine genres.Together, these labels begin to describe a family of serious work that takes readers beyond what they’re likely to see on an average day.

The value of the stories in ParaSpheres lies in their power to transform and make sense of the world by offering a sense of other worlds and ways. In her introduction, “A Memoir in the Form of a Manifesto,” Rikki Ducornet calls for “subversive storytelling in which the world is reinvented, reinvigorated and restored to us in all its sprawling splendor.” Formulaic writing has a hard time with transformation, not only in hackneyed sci-fi plots but also in “literary” writing that represents— sometimes self-indulgently—the (reasonably) real while reinforcing the comfort of unconsidered ideas.

There is much in ParaSpheres that rewards careful reading.To help make their case, the editors include writers— Angela Carter, Ursula K. Le Guin—whose work has passed successfully beyond the publishing world’s genre boundary. Carter’s “The Cabinet of Edgar Allan Poe” is a surreal historical fiction that invites speculation about the traumatic genesis of Poe’s obsessions. Another noteworthy story, Stepan Chapman’s darkly funny “Losing the War,” is a timely fable in which villagers coax to its death an enormous, infant personification of War.

Morrison and Keegan have begun to make a case for their new category. It seems to describe what we wish for as well as what we should fear, whether in worlds beyond the “real” or in the apparent realities of daily routine, to which we are sometimes so slow to imagine alternatives.