“There are always hookers on Church Street.”

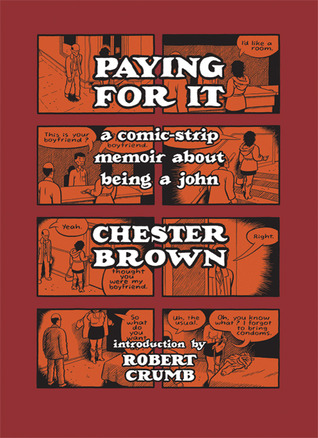

This seemingly offhand observation, made early in Chester Brown’s Paying for It: A Comic-Strip Memoir About Being a John, sounds like the punch line to a familiar type of joke, the “rabbi and a priest walk into a bar” variety. It has the same casual knowingness, the same intimation of transgression rendered as an informal bit of commentary operating on lowest-common-denominator assumptions that are not, perhaps, entirely unfunny. Not “ha-ha” funny but “huh? weird” funny, the frisson of tension suggested by the juxtaposition of hookers and Church. Mary Magdalene notwithstanding, we do not expect to encounter ladies of the night in the proximity of a house of worship. And so there is something positively quixotic in the notion of a pleasure seeker, in this case Brown himself—on his bicycle because he does not have a car—storming Church Street to find love by the hour.

As it turns out, there are no hookers on Church Street. Brown circles aimlessly, makes a detour, and finds only a cop car or two for his trouble. Prostitutes, he learns, are actually much easier to find on the back pages of the free Toronto alt-weekly. Or at least they were in 1999, when Brown first decided to reconcile the competing desires of his life—“the desire to have sex, versus the desire to NOT have a girlfriend”—by, well, paying for it. (Casual sex and one-night stands apparently do not exist in Canada.)

Yet the image of hookers on Church Street lingers. It is the memoir’s motif, its theme song, suggesting that the mingling of the sacred and the profane is both less and more complicated than we usually assume. Brown worries, early into his life as a john, that he might be participating in the exploitation of women, that his partners might be less than eager; but he also worries about how to reject escorts to whom he is not immediately attracted. If paying for sex is at first intended to help him avoid the snags and hitches of romantic relationships, the premier irony of his experience is that he forms attachments, that the transaction ultimately transcends a cash exchange. (Spoiler alert: at memoir’s end, Brown admits he is in love with a woman he met this way; he continues to pay her, but the relationship is exclusive.) “Paying for sex isn’t an empty experience if...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in