“And the best shot at resolution is what the title seems to imply: that the excess of passion from which such senseless violence stems must be un-felt.” This is one reviewer’s take on the central conflict of Ian Holding’s previous novel, Unfeeling. A boy witnesses his family’s butchering at the hands of roving militiamen and must resolve the problem of how to live with it. He must unfeel his own rage and hate, just as the volatile political climate into which he has been born must unfeel the scars of colonial racism that have defined its terms.

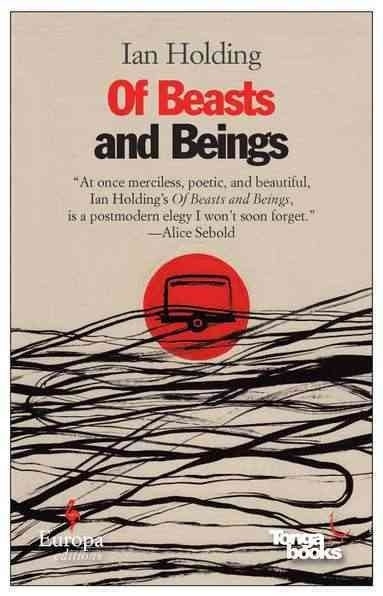

By contrast, Holding’s second novel implores its characters to feel. The narrative of Of Beasts and Beings is broken into two parts: the first chronicles the journey of an unnamed kidnappee hauling a wheelbarrow across the African countryside; the second, a series of journal entries, details the daily tribulations of a Zimbabwean teacher as he dismisses his servants, sells his house, and prepares to leave his homeland. At first the two segments are disjointed, the connection between them unclear, but over time Holding succeeds not only in bridging that gulf but also in connecting both sides to us.

How? The two narratives entwine toward the end of the book, but the more-relevant bond involves an implicit series of questions: how does the Zimbabwean experience affect me as a human? To what extent am I participating in my own reality? And in what reality am I participating, if not my own? In the first segment Holding answers these questions experientially, through bristling imagery, staccato verse, a vital rhythm that quickens like a heartbeat; in turn, this supplies us with the emotional raw materials we need to comprehend the analytical approach he takes to the same questions in the second segment. As the novel’s surgically precise prose unfolds, its percussive cacophony erodes our guard as readers: we feel the tedium and brutality of the barrow-bearer’s circumstance, feel for him even as he fails to feel—or be, or contain, or become—anything. And we feel for the schoolteacher, who struggles to make sense of an environment capable of birthing such pain.

The schoolteacher’s attempts to confront this world are not always satisfactory; eventually he concludes that all Zimbabweans, black and white, are trudging through a kind of un-life, stunted and stifled by circumstances that stave intractable rifts between them.“In that disjointed state,” he says, “we have grown up deformed, autistic, simpleminded, unable to reach maturity.” And sure enough, this is the very state embodied by the kidnapped man, who is forbidden to find any repose in the comfort of a goal or purpose. He seeks solace, near the start of his journey, in his belief that “this path must lead to somewhere that is a place, to somewhere that is an end result to [his] labours, to something that is a release of the pain.” Later in the book, however, he bemoans the fact that “the load should by now be absorbed into his own weight and his own body; becoming one with him. But he can never get used to it.” His solution is to resign, eventually determining that “the infinite solitude of freedom would probably finish him off.”

If it sounds like the story trends toward self-consciousness and meta-narrative, well, it does. Any novel written by a white man from Zimbabwe is going to be targeted at a largely white audience outside Zimbabwe; this is not a stylistic criticism but an economic fact. As Holding himself has stated,“There are no literary books whatsoever sold in Zimbabwe—mine, or any other.” So the central challenge of a novel like Of Beasts and Beings is to internationalize the uniquely Zimbabwean experiences that lend resonance to its narrative—in other words, to universalize the local. Holding succeeds in doing so precisely through the two-pronged narrative that initially resists unification: the first prong provides his white, non-Zimbabwean audience with a taste of the circumstances that render a novel like this so vital; the second tries to make sense of those circumstances. It fails, but in failing it only amplifies Holding’s message.

Of Beasts and Beings is about the guilt of having inherited something that you don’t want and can’t cast off, but that nevertheless defines you. It’s a guilt as loud and ineffable as the color of your skin, a guilt that cannot be resolved by generosity, or even service, labor, punishment, or slavery. The only atonement comes in the visceral human empathy we find when we share each other’s stories—in the precious, narrow spaces where that sharing becomes possible.