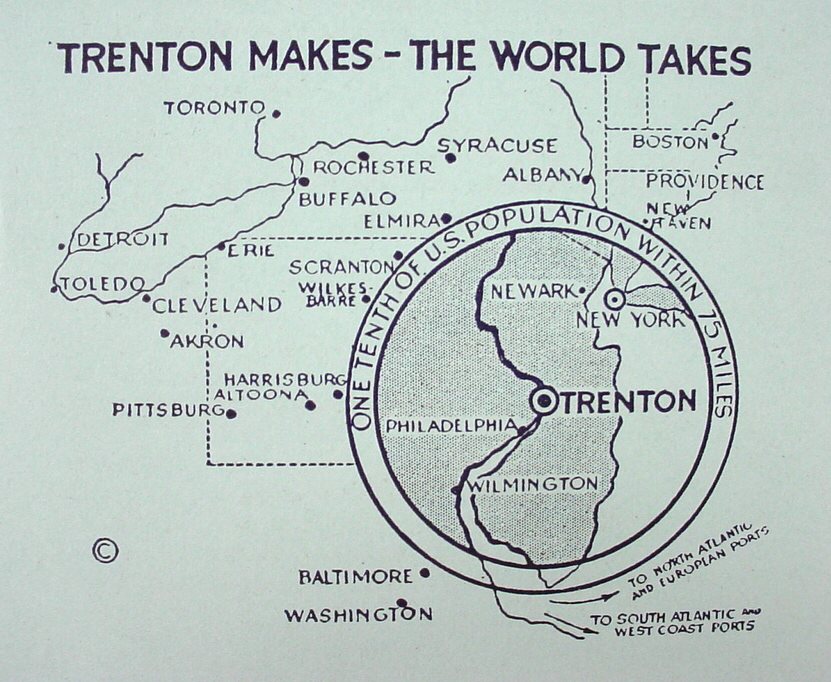

Format: 224 pp., hardcover; Size: 5.7″ x 8.6″; Cigarettes smoked or considered: 16; Population of Trenton, NJ, 1950: 128,000; Population of Trenton, NJ, 1970: 104,000; Percentage Change: -18.75%; Origin of “Trenton Makes, The World Takes”: Chamber of Commerce slogan contest 108 years ago; Representative Sentence: “It was there, in the dance she performed in the morning in their home, that Kunstler perceived the beautiful complexity of it, as if someone had snatched away a panel to reveal the intricate pattern of cogs beneath: the advances and retreats, the range of motions, the fluidity, the relationship to the music.”

Central Question: At what point does the performance of masculinity become destructive?

In Trenton, New Jersey, 1946, the war is over but has hobbled America’s men, leaving many of them hollow drunks, one-upping each other with vulgar jokes and paying dimes and nickels to dance with women in bars after factory shifts. One night, Abe Kunstler, veteran, drunk—a man who “without flinching fought and lied his way into a bare living along the Jersey coast”—comes home and again assaults his wife. His wife has grown strong in one of those same factories while the men were away, and a violent encounter ends with Abe bleeding on the kitchen floor, and later in the building’s basement furnace. She will become Abe Kunstler.

Tadzio Koelb’s manic, panicked novel of identity, Trenton Makes, is the claustrophobic journey of the new Abe. For Aeschylus, murder was the signpost past to which one couldn’t return, and a lie the murderer tells himself is that he can resolve the chaos he’s unleashed. This is certainly the case Koelb is making for Abe and the nation after their demolishing wartimes. To have lived violently is to have no release from a cycle of violence, and to seek outcomes that will again give this result. The result of the war is Abe’s assault, and the result of Abe’s assault is his victim taking his identity and beginning his life anew. The new Abe, setting out with no friends and no confidants and everything on rails, is surely headed toward confrontation and some unknowable, violent end, and will lie to himself as he descends toward this outcome. Koelb only refers to the new Abe, our protagonist, as he/him—there is no reality outside of the new reality of Abe, who wraps his breasts tight with bandages and repeats a vague lie about being “wounded in the war.” Abe leaves a wet razor on the sink’s edge, should anyone investigate his boardinghouse room, and sneaks down the train every morning to yell himself hoarse...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in