Post-writing

Editing

Supercut

Last month saw the publication of Dictionary Stories, a pan-generic collection of very short stories by Jez Burrows. The word “by” here has a peculiar depth: the constituent parts of each dictionary story come wholesale, or almost, from the example sentences that accompany definitions in one of twelve different English dictionaries. Meanwhile, at the end of last year, Troll Thread released Tom Comitta’s Airport Novella, which is likewise more assembled than created—in this case out of four gestures—nods, shrugs, odd looks, and gasps—as they appear, often, in the work of authors like Dan Brown and Danielle Steel. Both Burrows and Comitta challenge the parameters of fiction by blurring the lines between composition and arrangement, turning pattern recognition into a sort of prose mosaic masonry in which most of the writing, as Comitta puts it, is done with scissors and tape. We asked them to connect the dots between their respective techniques, aims, and inspirations; without so much as a shrug or a gasp, they obliged.

—Daniel Levin Becker

TOM COMITTA: So, why did you write Dictionary Stories? What led you to it?

JEZ BURROWS: I was reading the dictionary on a Friday night (because that’s the sort of white-knuckle life I lead) and I found this example sentence for the word study in the New Oxford American Dictionary, which read “he perched on the edge of the bed, a study in confusion and misery.” It was so melodramatic and unexpected, and it made me realize I’d never really given these sentences much thought before. I ended up just sat there reading the dictionary in a completely new way—which is to say completely disregarding the main attraction (the definitions) and instead focusing on these odd little pieces of fiction hanging out in a book of reference.

TC: In the introduction you talk about how you went from the “study” sentence, and happened upon another sentence that seemed thematically linked. You found other sentences that also happened to fit into this image of a depressed person sitting on a bed. When you combined them the image began to grow, the room around this unnamed character became untidy, etc.

JB: Yeah, it was actually another example for study: “he perched on the edge of the bed, a study in confusion and misery,” comma, “a study of a man devoured by his own mediocrity.” They seemed as if they belonged together. That was the flashpoint: realizing I had access to thousands of pieces of an infinite number of jigsaw puzzles, all of which could be any shape or size.

TC: You’ve taken these sentences and created everything from short short stories to lists to haikus. Would you call your book a short story collection?

JB: For the sake of simplicity, sure. There are a variety of forms, and technically I guess you’d call the prose sudden fiction or micro-fiction. I think the subtitle of the book, Short Fictions and Other Findings, is probably the most honest description. Plus, I like that it suggests something archaeological. I often felt like I was digging around in these areas of dictionaries that were, certainly not undiscovered, but not typically what people go looking for.

TC: Right. People go to the dictionary with a purpose. They want to be guided down the right path, to the right answer. What’s great about your book is that it totally inverts this purpose. Maybe this is just what narrative does. Narrative destabilizes. It doesn’t have the same use or value as a dictionary. You’re drawing from content that is so centralized and codified, and giving some air to it.

One of the things I’m interested in as a writer of collage fiction is how much the writing is guided by the source material itself (i.e., the possibilities and limits built within it) or by the author. Your book is basically 99.9% unoriginal language. You’ve added conjunctions and changed some verb tenses, but minimally. By writing almost entirely with sourced material, your book becomes “about” dictionaries—it’s almost a study. I’ve noticed that in your book there are a lot of naval stories, pep talks, and references to religion. There are also a lot of brawls. I’m curious how much the source material drives your narratives. Is each story a collaboration between you and the dictionary? How much are you the author?

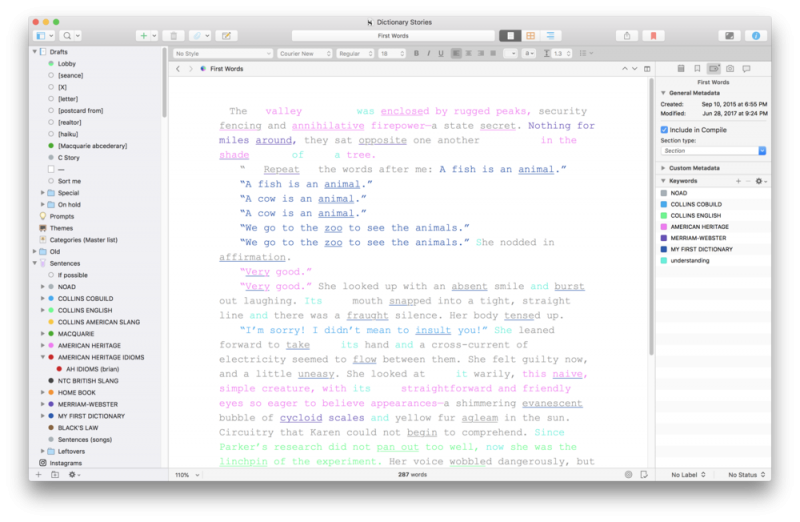

JB: I’m really fascinated by this, too. There are a lot of fights, and generally a lot of characters losing their minds, but that could just be the result of writing anything in the first half of 2017, as I did. I don’t have a strong connection to the sea, or to religion, so who knows where that’s coming from. I definitely see the book as a collaboration, though—so many stories in the book only exist because I found a single sentence that suggested a whole approach. Some sentences seemed inextricably linked to certain genres (murder mysteries, romances, noirish thrillers), while others weren’t remarkable by themselves but became interesting in aggregate when put into categories. I’m looking at Scrivener right now, which is what I used to collect and categorize everything that I found, and in the New Oxford American section I have: arguments, art, babies, bodies, booze, buildings… there are hundreds.

Sometimes it wasn’t the content of sentences that suggested stories, more the linguistic structure: At one point I found a ton of two-word examples in the form of adjective, noun—“seasonal rainfall,” ”overproof rum,” etc. As soon as I found them I knew I needed write some sort of peculiar menu or recipe. There are lots of examples, but overall I definitely tried to let the dictionaries guide me as much as possible—I was more interested in writing a book that revealed something about its source material than it did about me.

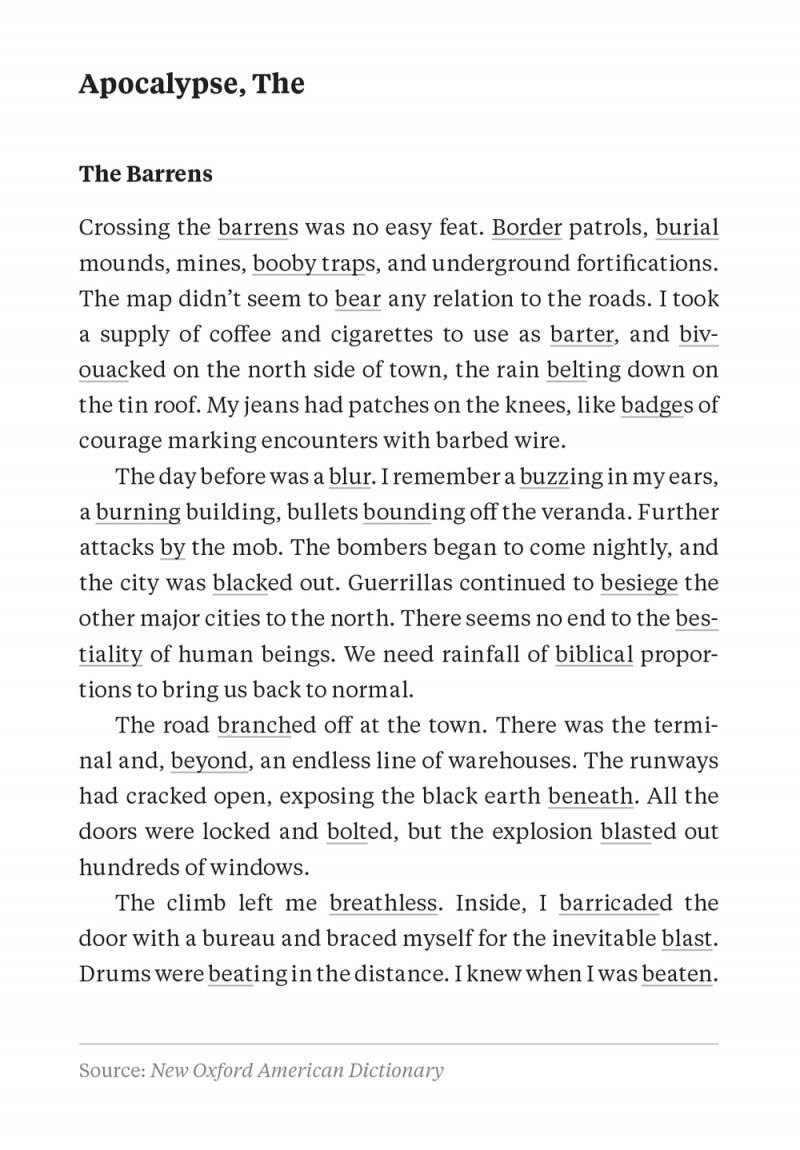

TC: I’m curious about a particular moment. One of my favorites in your book, “The Barrens,” is an apocalyptic narrative of a character moving through a dead city. All of the example sentences used to create this story are for words that begin with the letter b. Reading this I wonder, is there something about b-words that is inherently despairing? Or was the lexicographer just having a bad day…?

JB: To your first point, there could be a lot of especially dark content in the b section of the dictionary, but for that story I specifically went looking for sentences that would be at home in an apocalyptic narrative, so it might be more to do with my filtering than anything inherent in b-words.

To your second point, this idea of a lexicographer having a bad day: I think the assumption you’re making (which is one I definitely had at the beginning of this project) is that lexicographers are writing these sentences from scratch, and that consequently they might be able to surreptitiously imbue them with a personality. The truth is that there’s a very specific set of criteria that example sentences need to meet, which demand a much more rigorous process than one person writing them from scratch. Linguistically speaking, they need to be very tightly constructed, but at the same time they need to be unremarkable enough that they don’t steal focus from their goal, which is to demonstrate the most probable or likely usage of a word. The process of “writing” them actually involves these enormous corpora of texts made up of anything from novels to scripts, articles, essays, and so on. Lexicographers search the database for a word and are given a huge list of usage examples. From this they can ascertain the most probable usage, pick a fitting example, or write one that represents the average usage. I’m certainly not doing justice to the whole process, but suffice it to say, the idea that the personality of a lexicographer on any given day would have any sway over the examples they write or edit is pretty unlikely. Although I didfind an example sentence in one dictionary, an example of “yield” that read “our dictionary yields to none,” which I love imagining as inter-dictionary beef, or maybe the lexicographer’s battle cry.

TC: Either way I think “The Barrens” a good example of how these texts work: there’s always a double reading. There’s a narrative on the page and then there’s the knowledge of the source material combined with what you’re reading. The two readings create friction. Fiction? Oh boy.

JB: I wonder how that friction differs between Dictionary Stories and your book City of Nature, given the inherent differences in their source materials. Example sentences are tightly constructed, often very short, and their entire purpose is to be instructive. In City of Nature, you use extracts from a huge variety of fiction, often whole passages as opposed to just sentences, and all of them are specifically describing nature. I’m curious how those characteristics informed the construction. Remind me again how you’re grouping it all? Is it by season?

TC: There are macro-groupings (like different seasons, geographies, weather patterns) and micro-groupings (like different animals, plants, clouds, times of day, phases of the moon). The seasons, geographies, and weather patterns guide the shape of chapters and scenes, and the animals, plants, clouds, and times of day become characters, transitional elements, fine details, and so on. When I wrote the first draft, the macro-groupings lined up neatly into a complete book structure: the first four chapters are the four seasons followed by an ocean chapter and a jungle island chapter, then outer space, prairie, mountain range, and desert chapters. Every chapter is linked in some way. For instance, the spring chapter ends on a beach looking out at the ocean, and the next chapter—ocean—begins moving swiftly offshore; the island chapter ends looking up at the sky with the line “Heaven was a partly cloudy place” (Don DeLillo’s White Noise), and the next chapter begins in “heaven”—right outside the earth’s atmosphere.

JB: I love it. It’s so lyrical and sweeping, but at the same time there’s that double reading—constantly reminding yourself that none of these sentences originally belonged together, and yet everything connects so gracefully. I’m totally in awe with the scale of it, too; I quickly found that, at least when writing prose that needed consistent characters or settings, there was a maximum length of story I could write for this book.

TC: Yeah, the inherent constraints to composing a book entirely with sampled texts are fascinating. We’ve talked previously about collage novels like Graham Rawle’s Woman’s World, which is much more lax in its constraints.

JB: Woman’s World sidesteps a lot of those constraints by being a literal collage novel—it’s assembled from thousands of snippets taken from mid-century women’s magazines, like a very elegant ransom note. Consequently it’s very easy for Rawle to have consistent elements like characters and settings, as he can literally construct them letter by letter, whereas the content we’re using makes it a lot harder to engineer those things.

TC: I also recall hearing he wrote out the entire novel before starting to collage. To your previous point, I should add that I do think my novel has characters, just not your typical ones. Even weather language takes on moody, character-like qualities when you place enough of it together. Storm language rages; rain is melancholic (“the ground sobbed,” from D.H. Lawrence’s White Peacock); but the sun almost always returns with a smile. Unless you’re in a hot desert or prairie—then it’s villainous. Because it maps these patterns, I often see City of Nature as oscillating between narrative and data analysis.

As for entirely sampled/non-inventive novels that do use human characters, two other books come to mind: Joseph Kosuth’s Purloined: A Novel and The Best American Book of the 20th Century by Société Réaliste. Kosuth’s book collages full, photocopied pages from other novels and Société Réaliste collects one thousand sentences from best-seller novels published in the 1900s. Both books are great ideas, but they’re basically unreadable—at least not for any sustained period of time. This is fine (like a lot of Conceptual Poetry, reading isn’t the main idea), but it seems so easy for collage work be disjointed. I’m interested to see what else it can do. And I’m endlessly curious to find who else is writing fiction like this, which was one of the delights of discovering your book. I think you’ve done something really compelling with the form. There’s obviously many ways to do it—I feel invested in collaging other fiction, but it’s been nice to see you drawing from elsewhere. Also you’re writing more than stories, making lists and haikus, and your content seems to have driven you to those forms.

JB: It did. There were some outside influences floating around in there too, though. What’s interesting is that I think both of us found some formal inspiration for our collage work in sources that weren’t actually literary. For example, I know that Airport Novella, the book you put out last year, owes a lot to this video piece by People Like Us. Forgive me if I mangle the synopsis, but Airport Novella is a book of four chapters, each one collecting instances of four gestures taken from the kind of bestsellers you find in airport bookstores (legal thrillers, romances, and so on), and the gestures being: nods, shrugs, odd looks, and gasps. The People Like Us piece also collects four kinds of gesture together, right?

TC: Right. The People Like Us (Vicki Bennett) video is called “DrivingFlyingRisingFalling.” Bennett combs through classic movies and finds patterns throughout—driving scenes, helicopter scenes, people flying and falling through the air. Watching the driving section you notice certain cinematic tropes that seem to run through driving scenes. There’s the odd looks between passengers and drivers, the wide-eyed swerve, the near car crash. In the video Bennett bounces back and forth between at least ten movies, creating the feeling that we’re in a car that keeps shape shifting from one movie to another. Like with any good supercut the video makes you wonder about the ubiquity of these repeated patterns. Why is it so easy to collage a continuous driving scene out of different movies? What other habitual patterns are out there that we don’t notice? Hopefully Airport Novella does something close to this effect as well.

JB: I just found that curious because my other touchstone for Dictionary Stories was The Books, who were this band that combined composed acoustic music with hundreds of found pieces of audio taken from, I believe, home videos, instructional videos, books on tape, anything they could find at garage sales. [1] It’s playful and intricate but also incredibly poignant.

They also made these really interesting pieces that almost feel like distant audio cousins of what we’re making. There’s one called “Millions of Millions,” which collects every time a single voice reads dollar amounts in what sounds like a press conference. There’s another called “Ghost Train Digest,” which condenses what I imagine is a very starchy British horror movie into three minutes. They definitely have this zeal for working with unlikely source materials that I think both of us share.

TC: I should clarify that Airport Novella’s four-chapter, four-gestures structure was inspired by that video by People Like Us, but the idea came from elsewhere. I was actually collecting nature descriptions for City of Nature when the idea showed up. Sometimes I’ll skim source books for descriptions, but often I’ll use Ctrl+F. While searching for “leaves” in Bret Easton Ellis’s The Rules of Attraction, I found few green things on trees, but many instances of people freaking out and leaving in the present tense (“she leaves” or “he leaves”). I gathered all of these “leaves” together and found they formed a pretty amazing dance. Somebody would leave, slam a door, and “Then I went to Greece and it took me a day to get to where the ferry leaves.”

After discovering this pattern, I started to look for other gestures in other books. Interested in the visuality of these described gestures, I turned to the most cinematic of novels—airport novels—and soon I found four gestures that were ubiquitous: nods, shrugs, odd looks, and gasps. There were other repeated gestures I considered, like laughing and sighing, but those four gestures appeared more frequently. One side effect of writing Airport Novella’s is that it’s changed how I read. I’m currently halfway through William Gibson’s Neuromancer, and it’s now distorted because he uses lots of nods and shrugs. I wonder what reading nature descriptions will be like once I’m done with that book.

JB: Yeah, I worry you may have just ruined a lot of books for yourself. Wait, before I forget, wasn’t there another video piece that led to City of Nature?

TC: Yeah, a friend of mine, artist Kota Ezawa, had made a video called City of Nature. The video collages and rotoscopes nature shots from feature-length movies into a supercut: the rivers of Fitzcarraldo cut to the rivers of Deliverance which cut to the rivers of Rambo which flow to sea in Jaws and so forth. Kota had invited me to perform at an art opening, and I decided to try something similar with novels. I collaged together a short story using nature descriptions from about twenty novels, but soon after the reading I thought, well, now I’m fucked: I have to write a full novel. The text has to take the form of the content it’s drawing from.

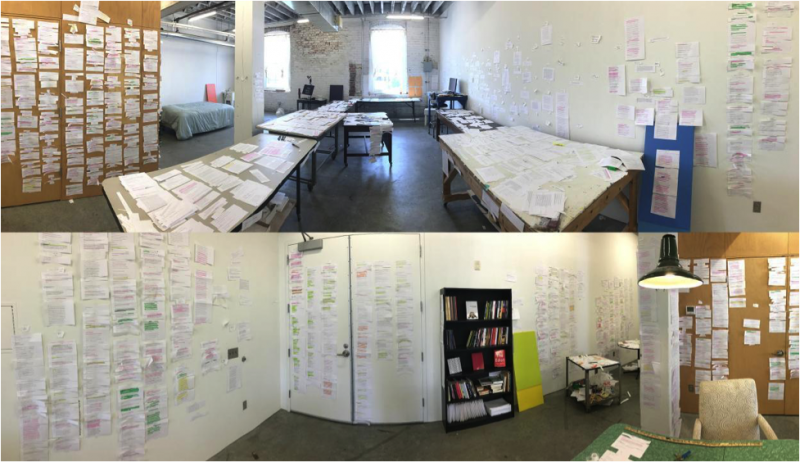

JB: Speaking of being fucked, I’m looking at some photos you sent me months ago of your workspace while writing City of Nature. I don’t want you to take this the wrong way, but they seem one ball of red twine away from a lunatic conspiracy theorist’s basement. I can almost picture you darting between walls, chain-smoking and talking to yourself. My process for writing the book was almost entirely digital, but this looks like what the inside of my head felt like—hundreds of print-outs and clippings arranged in piles or stuck on walls. Could you explain to me what’s actually going on in these pictures?

TC: What I do is a combination of digital and analog. The pictures you’re referring to [above] were taken while in-residence at the Bemis Center in Omaha, Nebraska in 2016. Before the residency, I’d spent a year going through ebooks collecting nature descriptions—I collected about 1,500 pages. In Omaha I printed them out, cut them all up, and just started putting them into categories. Each season had its own table or half-table; there was an ocean table, desert table, etc. On each table I would separate the piles into the micro-categories I described before: forest language, river language, sky language, different animals. And then sometimes the categories got even more specific: phases of the moon, storm language at night, storm language in a snowstorm. What you see on the walls is my attempt at writing the book, which is basically an interaction between all of these micro- and macro-categories.

But there’s also a pace that drives everything—something you can’t see in the photo, but in how the text reads. I’m trying to achieve a really smooth collage, with no big jump cuts. It’s off-rhythm in this book to have a really happy description and then a suddenly violent one. Violent storms build gradually unless there’s a section break. Even then, there’s likely some foreshadowing. I do all of this because I want to maintain a kind of non-human, glacial pace, a cohesion that is almost eerie—these fragments from all over the place, written across geographies and time come together and have a conversation. Sometimes there are humorous moments. In the first chapter there’s a morning scene where thousands of birds sing in ecstatic praise to the rising sun. Birds chirping in Finnegans Wake next to birds in about fifteen other books. Looking at these descriptions, it’s interesting because you notice that the language in a book like Finnegans Wake is so much stranger than 99 percent of all other novels, and you start to see that the range of how people describe nature is quite small. Some things are bizarre, like how D.H. Lawrence can’t help but sexualize spring as a female body. The number of hills and clouds described as breasts in his spring language is totally ridiculous. Of course he’s not alone in using nature in this way—personification is an easy way for a writer to be an asshole, and it’s used incredibly often in nature descriptions. Also repetition is everywhere: I found at least five books that described the jungle as a cathedral. My book gathers them into a cohesive, somber moment. Then later in the desert chapter there’s a passage from The Professor’s House by Willa Cather that describes mesas as “vast cathedrals” and “piles of architecture.” Images and metaphors kind of echo throughout.

JB: I like that you’ve confirmed my lunatic comment but in the best possible way.

TC: I mean, you have an image of a book you want to write, and you work toward it, right? Airport Novella was not as involved; with a smaller set of sampled material, I was able to work primarily on the computer, and it took far less time. This book just demands more and so I’m giving it the time. Writing City of Nature I do use the computer quite a bit, but most of the writing is done with scissors and tape; I can’t imagine writing it all digitally as you’ve done with Dictionary Stories. It’s not a critique; I’m in awe of the fact that you were able to produce this book entirely on the computer. Although we emailed earlier, and you said you wrote a few stories by paging through a bound dictionary.

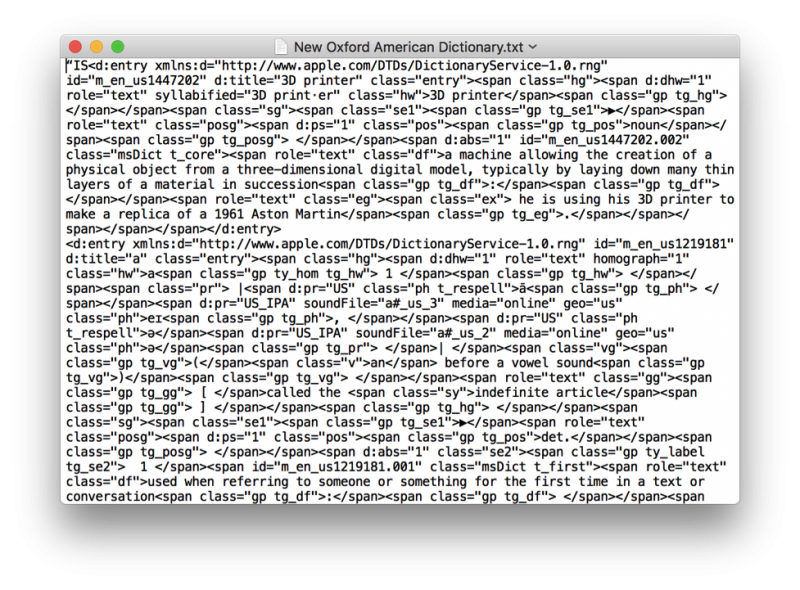

JB: It went through a few phases. The earliest stories were written using the dictionary included with MacOS, and that process was very linear and just… glacially slow. One sentence at a time, one story at a time. It felt like trying to look at a mountain through the eye of a needle—there’s so much there but you can only browse it in this hyper-focused way. Later, a friend of mine was able to extract the content of the New Oxford American (which the MacOS dictionary references), and gave me one enormous text file with the entire dictionary inside. This let me search for the content of example sentences instead of definitions, which is not usually something you can do. Not only that, but I could also be very specific in the kind of examples I was looking for—I could find a sentence that began with “I am,” or “he is,” or ended with a question or an exclamation point. I could find sentences using specific vocabulary, or sentences that were exactly ten words. It was a huge step forward.

TC: Why would ten words matter?

JB: Oh, I just use ten as an example, though I did search for examples with specific numbers of words just to see if there were interesting patterns. One thing I didn’t realize is that suffixes and prefixes have their own listings, and their examples are often just one word. So there’s an entry for “-ation” which has the words “exploration” and “hesitation” listed as examples. I started getting really into what structures were recurrent throughout the dictionary. You can use a wildcard when you search in TextEdit, which meant that I could search all of New Oxford American for sentences with a particular construction, like “the x of y,” to use just one example: “the awkwardness of youth,” “the bleakness of winter,” “the church of England,” and so on.

TC: Did you code that yourself, or did your friend help you?

JB: Oh it was literally just a plain text file that I was opening in a text editor. Anyway, that worked wonders for the New Oxford American, but I still had eleven other printed dictionaries that I couldn’t search as easily or as quickly. Eventually I found this company somewhere in upstate New York that scans books in much the same way as Google Books once did. You send them a book, they scan and OCR the contents and send you a searchable PDF. I then had twelve digital versions of the dictionaries I was using, which gave me a ton of flexibility but also a sort of paralysis in the face of so much material to draw from.

TC: I can imagine. With a dictionary it’s almost as if you have the universe at the tip of your fingers. The dictionary is basically the known universe described. There are constraints inherent in the content of example sentences, but then the possibilities are also very wide.

JB: For sure. Even though example sentences are so focused, we’re still talking about a dozen two-thousand-page books full of… everything. The potential is kind of dizzying.

TC: But then there’s also a constraint inherent in trying to produce a story by finding commonalities between disparate fragments. Sometimes they just don’t fit together. I’m curious—were something like seventy percent of the example sentences you found unusable?

JB: Certainly a lot harder to work with, but I wouldn’t say unusable. If I learned one thing about working with this content it’s that everything will work somewhere if you wait long enough. When I found “do not admonish little Stanislaus if he tears the heart out of a backyard sparrow,” [2] I loved it, but presumed it was too peculiar to ever find a home, but later I found myself writing a piece where a parent was leaving instructions to their babysitter for the evening and I suddenly remembered I had this insane sentence in my back pocket.

It’s funny that you mention constraints in the content itself, though, because using my own constraints to write stories was how I managed to break out of that paralysis of choice problem. Actually, perhaps we should mention Daniel Levin Becker at this point, this connecting thread between the two of us. I met Daniel after reading his book about his experience with the Oulipo, which was hugely inspirational to me in thinking about constraints. There’s this part in the book where he discusses the ethos of Oulipian workshops, and how if you sit someone down and just say “write poetry,” you will likely be met with someone looking very helpless. But if you say “write poetry without using the letter e,” or “without using any letters with an ascender or a descender,” you are instead giving them a puzzle to solve that just happens to generate literary content. So I tried that theory on myself and set constraints on the type of sentences I could use—their order or their content or their length, etc., just to see where it led. You mentioned “The Barrens”, which only uses sentences from the bsection of the dictionary. “I Was” is a monologue that uses only sentences that begin “I was…” There are a couple of abecedaries, which are made up of twenty-six sentences exactly, one taken from every lettered section of the dictionary, in order. Those were probably the most difficult to write because there are obviously some problematic letters.

TC: Which one is that?

JB: “X” is a nightmare, obviously. “J” is surprisingly difficult.

TC: No, sorry, which story is the one that moves through the alphabet?

JB: Oh! Well, one is called “July 8.” It begins “I found an English garden all about me” which was an example of “about.” Then the second is “peach trees in blossom” and then “cut grass.” It’s just this character ambling through this English garden and talking to himself, but it hangs together quite coherently, given how narrow the constraint is.

TC: These stories and many others in your collection use constraints, but I’m also curious if there’s a connection to supercuts. It’s something I’ve wondered about my own work and some other writers—particularly poets—in our generation: are we creating supercuts? The form seems part of our cultural vocabulary.

JB: For sure, it’s well established at this point. Just ask Lorde. But when I think about supercuts in relation to the work we’re making, there seems to be a key difference, which is generally: supercuts pick a single action or a motif or whatever it is, and just collect together like instances of that thing.

TC: Right.

JB: I’m generalizing, but there’s often not much emphasis on the sequence these clips are in. Something like “Sit Down and Shut Up: The Supercut” can really work in any order, for example. Which is not to say that there’s no thought given to editing there, but it’s perhaps more straightforward to piece those clips together than say, nature descriptions or example sentences.

There are a couple of pieces in Dictionary Stories that you could argue are closer to those kinds of supercuts, in that they group together sentences with similar linguistic structures or themes—but they aren’t just lists, there’s an attempt to actually create a story there. Much like in Airport Novella: you’re not just finding a bunch of “odd looks” and cramming them together into any order. [3]

TC: Right. There’s a spectrum of supercuts, particularly with regards to how they’re edited (or in the case of writing, written). [4] There are finely edited supercuts and there are supercuts like the one you describe above. It’s choppy, but it doesn’t matter because it’s making a simple point. A literary equivalent wouldn’t be as readable as our texts—it would likely be a list poem that you’d skim. At the other end of the spectrum, there are supercuts in which editing, pacing, and narrative are more of a concern.

I’m thinking of videos like Christian Marclay’s 24-hour collage of clocks and watches from film history, The Clock, and the Anti-Banality Union’s “feature-length autops[ies] of Hollywood” Police Mortality and Unclear Holocaust —the former collects scenes from police movies, and the latter collects scenes of alien invasions and natural disasters descending on New York. Both Anti Banality Union videos recombine found movie clips into traditional feature-length narratives replete with rising action, climax, and denouement. It seems to me that our methods of writing, which adopt traditional fiction structures like the novel and short story, have more to do with these kinds supercuts than their choppier cousins.

I also wonder if a term like “literary supercut” might be useful to clarify the difference between our books and collage fiction by writers like William Burroughs and Kathy Acker. What we’re doing is more strictly concept-driven, and we’re not inventing any characters or settings (personally, in books like Airport Novella and City of Nature, I don’t add any original words of my own). And, just as with video supercuts, we stick to constrained sources like dictionaries or novels. It seems we’re not doing it like they did in the ’60s or ’70s. I think we’re even doing something different with fiction than what David Shields proposed more recently in Reality Hunger and his other writings—his theories of literary collage are more invested in the blending of original and found text (autofiction or autotheory) than literary supercuts.

JB: I could get behind that description. The other interesting aspect to me about supercuts, or at least those you’ll typically find on YouTube, is that they’re such a powerful expression of fandom. I feel as if you need to love something so intensely to trawl through hours of footage and edit it down to a ten- or twenty-minute long video. It feels like such a modern response, too, particularly where film is concerned: instead of creating art inspired by other art, you’re creating art with the art itself because the tools are so readily available. You can download the entire filmography of one actor or director in the space of afternoon, edit it using free software, upload it for the entire world to see… none of which were possible, as you said, in the ’60s or ’70s.

TC: I like your idea about fandom. I also wonder if the supercut is a form like any other—like the sestina or writing in quatrains. There’s a clear structure to follow, but whatever the writer/editor brings to it aesthetically, politically, etc., determines what it does. While fandom might be a driving factor for some collagists, I think many also use it as a form of critique. John Oliver uses it to critique news media and Anti-Banality Union collages to critique Hollywood representations of cops and disasters. It seems the supercut is just a form waiting to be activated for whatever purpose. But to your point about fandom, it does seem that most collage work draws from pop culture. Collagists and supercut makers often use our shared vocabulary of actors, songs, movies, ads and, in our case, books. The Romantics used trees, but now we use celebrities and mass media to talk about things.

JB: Exactly. If you’re making a supercut about, you know, the Marvel cinematic universe, you can speak in a language entirely made up of enormous explosions and grand visual flourishes, which, if you aren’t a director or a filmmaker probably feels pretty empowering.

TC: Yeah. There’s a larger toolkit to work with. One of the byproducts of working like this—drawing from mass media—is that the work inevitably leans toward “the pop.” Even a collage like Dictionary Stories has a kind of pop sensibility. Many of your characters are iconic. I feel like I already know them. Maybe it’s because many of them are pastiches of common genres (noir, apocalypse narratives, seafaring voyages). It’s really fascinating that you’ve also pulled this sensibility out of these reference books. That you’ve found it there.

JB: I guess that’s just what happens when the corpora used to source example sentences are composed of public domain texts—all the pop tropes and cliches are in there somewhere. Somebody in a novel or a script wrote the sentence “he watched the time machine dematerialize,” a lexicographer used that as an example of “dematerialize,” and I borrowed it once more to put it into a different time travel story. It’s like a cultural relay race.

TC: That idea resonates with other metaphors people have used to think about collage art and writing—that culture is always recycled. That we’re always drawing from elsewhere, recombining, redoing. Maybe this kind of work is just part of an organic drive to respond and share.

JB: I think that’s an impulse that doesn’t depend on time or genre. I think that’s innate in people who engage with art on any level.

- [1]

“They’re sadly now defunct, although both members (Nick Zammuto and Paul de Jong) now make music under their own names. ↩

- [2]

“An example of “admonish” from Australia’s Macquarie Dictionary. ↩

- [3]

““I Was” uses only sentences that begin with “I was…”; “Rains” uses only sentences that include the word “rain” somewhere in the sentence, etc. ↩

- [4]

TC: The first time I performed City of Nature my friend, poet and novelist Kevin Killian, joked that the text was “post-writing.” More recently another friend, poet Danny Snelson, described how he’s more interested in thinking of collage writing as “editing.” I’m fascinated by both lines of thinking, especially since they offer explanations of what we’re doing as not writing, but something else. Also, Danny’s term clearly connects literary and video supercuts. For purposes of clarity here and because I’m not ready yet to take the leap into other terminology, I’m calling what Jez and I do “writing.” ↩

Jez Burrows is a British designer, illustrator, and writer, living in San Francisco.