Go Forth is a series that offers a look into the publishing industry and contemporary small-press literature. See more of the series.

A Q&A with Marcela Sulak and Jacqueline Kolosov

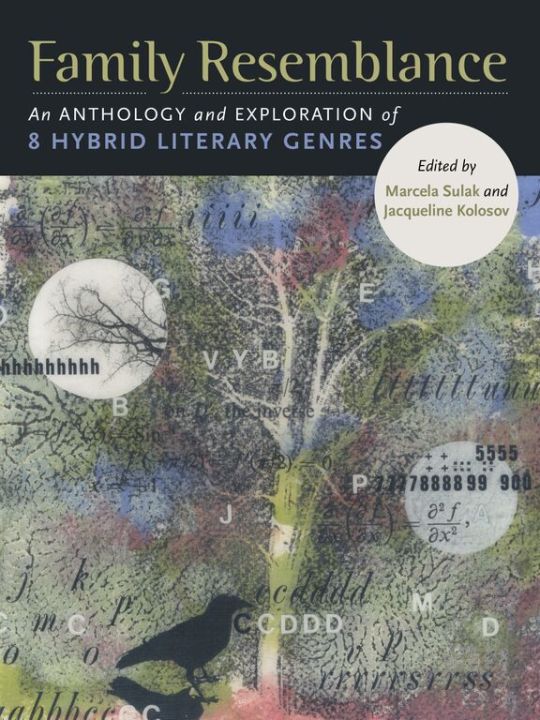

Family Resemblance: An Anthology and Investigation of 8 Hybrid Literary Genres, co-edited by Marcela Sulak and Jacqueline Kolosov, is forthcoming on November 4 from Rose Metal Press, and features essays and examples from 43 contemporary hybrid authors, including Nick Flynn, Terrance Hayes, Sabrina Orah Mark, Maggie Nelson, David Shields, and Khadijah Queen.

In early October, Jacqueline, in Texas, and Marcela, in Israel, chatted over email about how the collection came to be and why hybrid literary work is more important today than ever.

JACQUELINE KOLOSOV: What’s the first work that you recognized as hybrid?

MARCELA SULAK: For me it was The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy,

Gentleman.

I was studying 18th century political thought and literature as an undergraduate at the University of Texas, where we read Hobbes, Locke, and Hume, as well as Lawrence Stern’s Tristram Shandy, Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, and Daniel Dafoe’s Moll Flanders. All three of these novels are hybrids—the latter two are epistolary, and Stern’s is ostensibly a fictional autobiography, but Tristram is notoriously more interested in the diversions the narrative takes than the narrative itself. He includes doctored-up sections of Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy, Francis Bacon’s Of Death, and Rabelais’s The Life of Gargantua and of Pantagruel, and many other works. Tristram Shandy exploded my head! It was like fiction on a psychedelic trip (I’m just guessing)—each sentence was radiant with the diverse atmospheres from which it was stolen (or borrowed). Each sentence was a doorway into an entire world, its sensations, politics, medical practices, gossip, and dining habits. These novels contained worlds—multiple novels, multiple points of view. I couldn’t believe you could get away with writing like that. I couldn’t believe that not everyone wanted to be writing like that all the time.

JACQUELINE KOLOSOV: Your answer coincides with mine. At NYU, I signed up for what I thought was a course in the 18th century novel. The professor, Anselm Haverkamp, a German historian, had us read the unabridged Clarissa, which brought me a good deal of back pain, Tristram Shandy, and The Sorrows of Young Werther, provocative hybrids all. We also read Habermas’s Theatricality and Absorption, and plenty of Roland Barthes. Though I was very confused about the nature of the course for the first month, it wound up being

among the most influential. And it ultimately makes sense that the 18th...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in