Josh Rosenthal on Singer/Songwriter Bill Fay

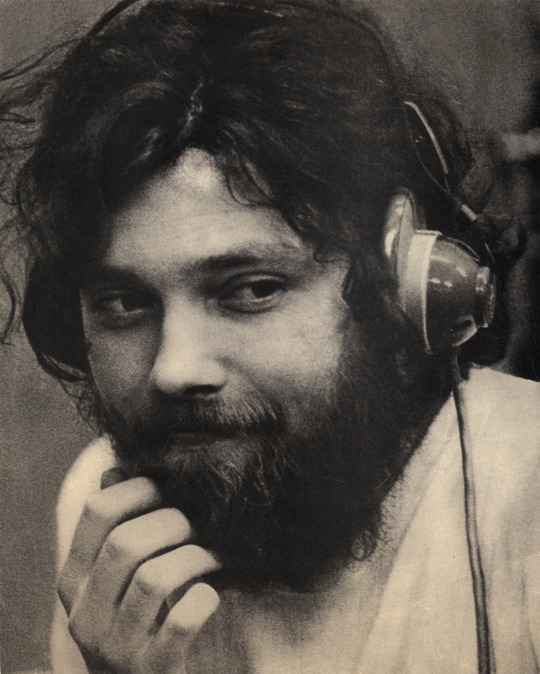

British singer/songwriter Bill Fay recorded two albums of musical interest in the early 70’s. His eponymous debut (1970) followed by ‘Time Of The Last Persecution’ (1971), both on Decca, are remarkable in their own right, and even more so considering how different they are from each other, released just one year apart. They represent one of the most compelling left-right combinations in rock music history, akin to how Leonard Cohen’s raggedly glorious ‘Songs Of Love And Hate’ immediately followed the well-mannered ‘Songs From A Room.’ Fay’s debut features grandiose orchestral arrangements that blast his miniature character studies into the stratosphere. Like Scott Walker’s early solo LPs, it’s cerebral, rococo English orch-pop. The second LP is experimental, spontaneous, and influenced by acid rock and Bob Dylan. Pictured on the cover of the self-titled debut album wearing an overcoat, walking over shimmering water in Hyde Park, a clean cut Fay gazes wistfully into the camera. By contrast, on the second album we find him with downcast eyes, unkempt beard and wild hair. “It wasn’t a set up or a pose,” Fay told Flashback magazine in 2014, “It was serious music, and I was concentrating. But people always read meanings into things, and they assume that because I had a beard I was undergoing a drug meltdown or personal problems of some sort. I wasn’t.”

That same sort of speculation swirled around Fay’s conspicuous decades-long absence after Decca dropped him in 1971. Fay dismisses the typical “script” that often accompanies commercial failure and disappearance – the descent into drugs, mental illness – rejecting any portrayal of himself as a “tortured artist.” Instead, he never stopped writing or recording. The period of 1977-1982 was especially fruitful, but no record company was interested in releasing his work. It wasn’t until the late ‘90’s that whispers of Fay’s legend started circulating, the result of various archival CD releases and MOJO Magazine mentions. A collection of early demos from the first two albums along with other material, ‘From The Bottom Of An Old Grandfather Clock,” was released in 2004. A “lost” third album under the moniker of Bill Fay Group, ‘Tomorrow, Tomorrow, Tomorrow,’ featuring the magnificent “Isles of Sleep,” surfaced in 2005, as did reissues of the Decca albums. Incredibly, Fay released a whole disc of unreleased demos from the ‘Time of the Last Persecution’ sessions in 2010 as ‘Still Some Light’, which included a few never-before-heard songs that were left off the album, such as “There’s A Price Upon My Head” and “I Will Find My Own Way Back,” both as great as anything on ‘Time.’

Jim O’Rourke played Fay for Jeff Tweedy in 2001 while mixing Wilco’s ‘Yankee Foxtrot Hotel,’ and Tweedy would go on to play a key role in generating renewed interest in Fay’s work. They performed Fay’s “Be Not So Fearful” together on May 24, 2007 at Shepherd’s Bush Empire, with Tweedy gushing from the stage, “Since we discovered this man’s records six years ago I can’t think of anyone whose records have meant more in my life.” Fay returned the favor by recording the band’s “Jesus, Etc.” for his widely praised 2012 Dead Oceans “comeback” album, ‘Life Is People.’ Fay looks like a young Jeff Tweedy on the cover of his debut, and Fay sounds like an old Jeff Tweedy at times on his last two albums. Check it out, it’s kind of eerie.

Growing up in North London, Fay’s mother had a knack for playing tunes by ear on the piano, and her siblings played various instruments. Fay would write songs on the piano, eventually recording some at home in 1966. Terry Noon, manager of Honeybus and former drummer for Them and Gene Vincent, heard Fay’s demos and arranged a recording contract with Decca, which released his first single in 1967, “Some Good Advice” b/w “Screams In The Ears,” produced by Peter Eden and featuring a South End-based band called The Fingers. The single went quietly, and Fay spent the next few years playing with Honeybus, demo-ing new songs and working odd jobs. Through this period, Fay refined his songwriting, inspired by Procol Harum and books by French philosopher and Jesuit priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. Several songs on the debut LP, such as “The Garden Song,” dwell on the natural world, often with vague religious overtones. “It amazes me that that song could appear within ten minutes. It was a big step forward,” Fay shared with me. “It expressed lyrically more where I was as a seeker. There’s a lot of depth that would take ages to explain.” Record Mirror was rather unforgiving of the songs’ naturalist metaphors in a review from 1970: “ ‘Garden Song’ commences, ‘I’ve planted myself in the garden, between the potatoes and parsley.’ Pass the weedkiller, please!” While that lyric may not be for everyone, it’s an example of Fay’s knack for building out a pithy phrase or idea, letting it sit there quietly for a minute or two, and then suddenly whipping it into something grand, both lyrically and by way of jazz composer Michael Gibb’s swirling horn and string arrangements. “Methane River” also achieves these heights, moving from a plaintive woodwind intro to a cascade of brass and strings with the alternating anthemic chorus – first, “I cannot make it” – as in, make it across the poison river – and then a triumphant, rousing “You can make it” in the final chorus.

“A man he told me it’s not the methane

It’s your knowledge that blocks your way”

“The song came from talks I used to have with a friend, about how we name things and explain them away,” Fay told me. “It’s knowledge that blocks your way. Look at a tree – what is it? – it’s a living thing. You’re trying to reach a deeper reality, trying to wake up to the natural world around you, trying to get out of your own head. Not in a drug way. Seeing the impact of the natural world.”

Fay’s debut album was recorded in one day with an assembled crew of about thirty musicians, and mixed the next day. Guitarist Ray Russell was brought on board by Mike Gibbs and became friendly with Fay during those sessions. Russell took over production chores on ‘Time Of The Last Persecution’ when Peter Eden bowed out, apparently uncomfortable with Fay’s overtly religious lyrical content. ‘Time’ is influenced by Biblical themes, including references to Daniel and The Book of Revelation. “Lyrically, I now feel it’s immature in part, and was conveyed more perfectly on (Dylan’s) ‘Slow Train Coming,’” he says in typical self-effacing fashion. Ray Russell remembers, “We had long conversations along with drummer Alan Rushton who was also a big influence on Bill. Our talks would see the dawn rise many times. Bill talks about the Second Coming many times in his songs but songs like ‘Tell It Like It Is” when he says ‘Peace be in your bike and in your door keys and old friends that have passed away’ shows his commitment to people and that humanity and social commitment is where the basis of change will come from. He practices what he preaches.”

Like the debut, ‘Time’ was also recorded in one day, live in the studio without the thirty-piece string section and gaudy arrangements, most likely with a fraction of the budget. There are still some horns, and Ray Russell’s guitarwork is much more prominent. “The wailing guitar lines are based on the emotional content of Bill’s music,” Ray explained to me. “He wanted me (us) to have these very varied dynamics. Very few songs have that freedom. The restless nature of the music was really a demand for change.”

The opening track, “Omega Day” likely refers to de Chardin’s concept of the “Omega Point”, the point at which our consciousness and spirituality are heightened and converge. This theme runs through the album, played out in dust filled rooms, bars, at Kent State, in concentration camps, “Inside the Keeper’s Pantry”, songs with souls all looking for higher meaning while confronted with forces of evil. He reprises the idea of getting up out of your “chair” on a few songs, beckoning the listener to find spiritual enlightenment. Musically, the shift in instrumentation and studio approach reflected the fast-moving changes of the times. Fay told me, “When our second album came out, I felt it was progress in the wider world of music. It deserved more attention. It was very innovative and progressive. Within a few years, music was really progressing.” He goes on to cite ‘Abbey Road’ and Procol Harum’s ‘Home’ as important markers, although he bristles at the notion of any direct influence. “I definitely appreciated what others were doing, but I was finding more from the piano. I was looking for answers, so lyrically the songs would reflect that. I don’t think anything influenced me. I was bringing in the spiritual aspect. Around that time, it was like it all stopped – the labels didn’t know what was going to be successful. The music got more and more replaced by conscious songs replacing unconscious. I’ve always considered myself a ‘song-finder’.” Keith Richards and Bob Dylan have talked about this idea of songs existing outside the self, waiting to be siphoned, just as “The Garden Song” came to Bill in ten minutes.

Ultimately, ‘Time Of The Last Persecution’ is a plea for spiritual awakening, a roadmap for locating that “Omega Point”. Bill comes full circle with this idea on his 2015 album, ‘Who Is The Sender?, which can be thematically summed up as follows: The path mankind is staking out (wars, wrecking the environment) is unsustainable, and everything WILL change if people seek their Omega Point. Fay’s world-weary condemnations of man’s endless folly (think Randy Newman sans humor or irony) take on a Voice Of God quality on the recent albums, his earthy croak giving authority to even his most mundane lyrical turns. On ‘Who Is The Sender?’, he repeats phrases – “It’s all so deep”, “He gonna change this world”, “Bring us peace on earth”, “This can’t be all there is” – that in the hands of others might sound trite. But there’s nothing trite about an album that uses the word “saxifrage” in a song, or devotes a whole song to William Tyndale, executed in 1536 for first translating the Bible to English from Greek and Hebrew texts.

Unlike many tragic music heroes of the 60’s and 70’s, Bill Fay is still alive to enjoy an overdue round of acclaim here in the 2010’s, made possible by producer Joshua Henry and Dead Oceans. Bill’s incredulous response to all the dripping accolades is sincere, and very charming. When asked recently what he thinks of ‘Time Of The Last Persecution’ now routinely referred to as a “masterpiece,” (and one that commands four figure sums for an original copy), he politely deflects, “ ‘Masterpiece’ is a journalistic overstatement – I’d say ‘of musical interest’, myself.”