Madeleine Watts On Laura Poitras at the Whitney

In the diary she kept during the autumn that she moved to Berlin, Laura Poitras wrote that she couldn’t sleep at night. When she did, she had nightmares of being detained at military bases, receiving dozens of packages, falling from a great height. She heard the blood moving in her veins. She was afraid. Her laptop kept running out of storage even though her settings indicated that 16GB of space were free. She was never not being watched. She was sure of it. She moved apartments every few months and kept herself away from phones and the internet. “I’ve created my isolation,” she wrote, “so they win. They always win. I can fight all I want and I will lose. I will be destroyed, paranoid, forsaken, unable to sleep, think, love.”

It was under these circumstances that Poitras conceived of the exhibit now occupying the eighth floor of the Whitney in downtown New York, and during this time that she was first contacted by Edward Snowden, who in no small measure turned her life on its edges. Poitras is best known as the director of the Oscar-winning documentary Citizenfour, a real-time chronology of Snowden’s decision to leak damning NSA secrets in June 2013. The Snowden leaks showed just how fully our lives, and our communications with one another, are being watched. The leaks saw Snowden, Poitras and the journalist Glenn Greenwald lauded as heroes by some and branded as traitors by others. Citizenfour was the last film Poitras made in a trilogy of documentaries exploring the aftermath of 9/11, and that film, like all her work, was concerned with the age of terror, tactics of surveillance, drones, the use of torture, targeted killing, the machinations of power in the digital age. The documentation she was provided by Snowden forms much of the work on display in Astro Noise, the artist’s first solo museum exhibition.

Astro Noise surrounds the viewer with this documentation, much of it drawn from the Snowden archive, some of it drawn from Poitras’ years of filmmaking. In an interview with the exhibit’s curator Jay Sanders, Poitras says “there’s a lot of conceptual art that talks about violence or power in an intellectual way, but I want to expand people’s understanding emotionally.” This is political art trying not to inform you or cause you to rise up in protest. Poitras wants to make you feel something.

Because at what point does hearing and bearing the weight of the Snowden archive, the knowledge we all have of just how terrifying is the war on terror, how widespread and invasive the surveillance state, switch from being an act of outrage to an act of collusion? What resistance is possible? They always win.

*

There is dirty snow on the ground in New York. It is February. The wind is chilly and people are pale and sick of the winter and nuns in white robes stand by subway entrances offering to mark the foreheads of passers-by with the sign of the cross. I’ve been listening to “Girl from the North Country” all week on repeat, and it’s either bringing me down or it’s appealing to me because I’m already sad, and I’m not really in a state where I can tell the two apart. The sky over the Hudson is slate gray through the high glass windows of the Whitney. A writer I respect has told me that it might be an interesting exercise to come to a gallery and feel things.

When you enter the gallery space where Poitras’ exhibit is currently on display the room is dark and empty except for a single screen suspended from the ceiling. People sit by the walls and sometimes cross-legged on the floor. Films play on each side of the screen. On one side appear a series of slow-motion faces, in various states of distress, shock and muted disbelief. They are looking at the ruins of the World Trade Center in the days after 9/11. The audio track playing in the dark sounds like roaring and ghostly machinery. In the handout later on I read that it’s the national anthem as it was performed at a baseball game at Yankee Stadium on October 31, 2001, altered and looped. On the other side of the screen plays grainy black and white footage of two men being interrogated in lightless rooms in the weeks and months after September 11 2001. The men are chained and sitting on dirt floors. The prisoners are Said Boujaadia and Salim Hamdan, who were subsequently transferred to Guantanamo Bay. Soldiers with guns and black balaclavas wrangle hoods over both men’s heads as they take them away. The affect of the double-sided screen is visceral. You are reminded how one tragedy can and did lead to a string of morally dubious acts. The two sets of footage are like two intersecting roads. They represent a beginning, and the point at which those dubious choices began to be made. On the ceiling above the screen are flashing blue lights and I’m not sure whether or not I’m meant to notice them.

When I first walk into the room the screen shows a blonde mother and her blonde daughter looking towards the wreckage from behind the barricade. The mother looks haunted, shocked. The girl looks kind of confused, kind of bored. She puts her tongue out and curls it. She is very young. I was eleven when 9/11 happened, which makes me and the bored girl suspended in the room on the screen the same age. I sit on a bench against the wall in the dark, looking at those faces.

Even across the world that day was a watershed. Teachers rolled a television into the room and we didn’t have lessons. We just sat and watched the towers burning or wandered around the classroom. At lunchtime we were sent outside to eat sandwiches under the eucalyptus trees. It was still cold in Sydney, early spring. I remember sitting beside my friend Jessica, a Jehovah’s Witness who lived in a two-bedroom house on the highway with six members of her extended family, and I remember telling her I was afraid. She asked why. I told her I was scared that the world was going to end. And she said, “Well, the apocalypse is coming.” She was smiling. She advised me to come to a prayer meeting with her and her family; because there were only so many people who could be saved. Jessica was twelve. She was older than me, and I believed her.

I watched the faces on the screen, watched the men being interrogated in dirt-floored rooms, and I remember those months at the end of 2001 as being ones when the world and its machinations first began to look wrong. Some split from childhood I date to that period. A feeling that the world wasn’t safe. It was lonely.

So this is what I’m getting at—I was told to come to a gallery and feel things, and what I felt was lonely. And I was not at all sure if that was an appropriate let alone a responsible response to be having.

*

Prompting emotion is a kind of tactic, and an interesting one for Poitras to be using under the circumstances. We live in an atomized culture, where ideas of utopia and justice and hopeful futures are tarnished if not long gone, and the role of art to politics is hazy. There might not even be a form of resistance that’s possible anymore. I can fight all I want and I will lose. And maybe the most difficult thing political art can do in the 21st century is force you out of your natural complacency.

It occurs to me as I move between the rooms of the exhibit that it’s been a long time since I’ve been forced to think about art as something that might be deliberately trying to make you feel something. The swell in the throat is for other mediums, for films and music, or it’s for overblown romantics stuck in the nineteenth century, or it’s for teenage girls with too many feelings.

There was a period of my life when I was a teenage girl with too many feelings and I would spend afternoons sometimes wandering through the airy vaulted rooms of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, getting emotional about paintings and photographs. I believed in the idea of art-as-catharsis, believed that emotion should be dived into and swum around in, and that art was emotion’s ideal arena. Then at a certain point all that emoting about art started to seem embarrassing. Excessive. I absorbed the belief that emotion pollutes critical thinking. That it is unserious.

In Hold It Against Me, her book on emotions in contemporary art, Jennifer Doyle explains that, “emotion can make our experience of art harder, but it also makes that experience more interesting. It may make things harder because the work provokes unpleasant or painful feelings. It may also make things more complicated.”

Art that makes you feel is difficult. Difficulty, in most forms of art, is something that bears the weight of distinction, but art that engages with your emotions is difficult in an entirely separate way. Difficult emotions can be medicated, and feelings like depression or loneliness or terror can be fixed with pills to adjust faulty chemistry. From this perspective, difficult feelings are a problem for medicine. The pathological lens we apply to painful feelings makes it harder to examine difficult emotion as a valid response to structural inequality and broken institutions. To life as its lived, with all the pain it necessarily entails.

*

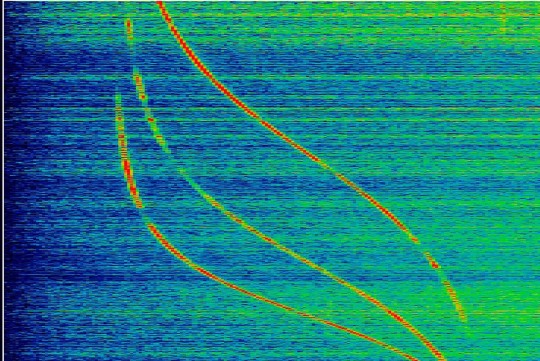

In 2013 the Snowden leaks were received with outrage on both sides of politics. If nothing else, the information contained in those files revealed the ways in which the surveillance state appears to pervade every part of our lives. When Snowden made contact with Poitras in 2013 he sent her an encrypted file containing documents that established the covert practices of the NSA and other associated agencies. He titled the file “Astro Noise,” which Poitras has borrowed as the name of her own exhibition. Astro Noise refers to the background disturbance of thermal radiation left over from after the big bang. It is detected in the form of microwaves that appear to pervade everything in the universe.

Further into the exhibit you encounter some of the raw data contained in the Astro Noise file. Documents and filmed interviews are viewed through small slits in the wall, as though they were still secret. You have to press your nose against the wall to see their contents clearly. This part of the exhibit is on the posters lining the 42nd Street subway tunnel. A woman in the dark peering through a slit into the light, as though Pandora was about to open her box. “You can see America from here,” says the poster. The poster sits between an advertisement for a Viking Exhibit at Discovery Times Square and a smiling Steve Harvey, his hands open beneath the phrase “Kids that make you say wow!”

This is the part of the exhibit where the fewest people interact. Bodies move from one slit in the wall to the next. We are all very quiet. I make notes. My boots are too big and my socks have slipped down and bunched around my arches and I spend time adjusting them by the wall.

In the weeks and months after the Snowden leaks, protest movements were formed around the world, loosely coordinated via social media. And then they gradually fizzled out. The thing that should feel shocking about the aftermath of the NSA leaks—but doesn’t—is that there was no real resistance movement born from the outrage. There was no “We Shall Overcome”, no sustained popular uprising. Instead, the reaction to the NSA leaks has been one characterized mostly by apathy.

The Day We Fight Back was organized in February 2014, a protest against the NSA organized largely around webpage banner advertisements urging readers to take action over cyber surveillance and a free Internet. Thousands of organizations signed up, but as the New York Times reported “the protest on Tuesday barely registered”, with many companies like Tumblr and Mozilla registering without including the banner, hiding the banner in an out of the way place like Reddit did, or, like Wikipedia, not participating at all. It’s not that the outrage about the Snowden revelations dissipated. People were still upset. But the collective reaction to the Snowden leaks moved along the same parabola as movements that had come before —the Arab Spring, Kony 2012, Occupy. In all of these movements that bloomed in the last five years, it’s not as though the underlying problem has disappeared, but the momentum peters out. There’s no sustained sense of collective organization to match a generation of short attention spans.

*

The Vietnam War and the cultural changes of the 1960s inspired a generation of artists to engage with politics, and turn to art-related activism. The director Michael Haneke infamously described his methodology as “raping the viewer into independence.” The idea this description gets at is that there must be something wrong with us. That we need a shock or violent rupture to release us from whatever our deadening condition happens to be, and whether that be apathy, alienation or narcissism it’s never clear.

A few weeks before the Poitras exhibit opened, Ai Weiwei restaged an image of a drowned Syrian child washed up on a pebbled beach in Greece. Ai lay on the beach in the same pose as the iconic photograph taken of Alan Kurdi the previous summer. Ai Weiwei is frequently depicted as a kind of martyr. His art is characterized by dissent, creating large-scale installations that address the corruption of government and the inefficacy of institutions. The photograph released of Ai Weiwei lying facedown on the pebbled beach in Greece was meant to comment on the international immigration crisis. By replicating the image of the drowned boy on the beach, what was Ai Weiwei dissenting against? What was he doing?

When I was a teenager my father took me to see The Battle of Algiers at an art cinema in Melbourne, and I remember less about the film than the trivia I absorbed about it afterward. The film was deemed so inflammatory that it was kept from being screened in France for five years, that the actors were nearly entirely unprofessional. Members of the Black Panthers would go to see the movie again and again, taking notes. Several years before I saw the film, in 2003, the Pentagon had held a screening of the Battle of Algiers for select officers and civilians. The invitation sent out to guests read, “how to win the war against terrorism and lose the war of ideas.” The guests would discuss what kind of lessons the Americans could learn from the Algerian war of independence now that they were fighting the war on terror, a war waged not against a country or a leader or a regime but a common noun. I loved the Battle of Algiers when I watched it in Melbourne in the art cinema, I loved that it was a piece of art that was part of radical political change, I loved that art could influence change. I was very idealistic back then, and I had a lot of feelings.

But the war against common nouns is still being fought and art, it seems, can only do so much, and when I began to realize those things, when my disaffection kicked in, I felt the same kind of loneliness that I felt when I sat under the Eucalyptus tree and Jessica told me the end of the world was coming and that it was unlikely that I would be saved.

And I tell you this story about The Battle of Algiers because it seems to symbolize to me all the ways that I used to believe that art could and should do something, and all the ways in which that no longer seems like the right question to be asking.

*

In the final room of the exhibition a small monitor mounted on the wall displays a steady stream of data. It is the mobile phone information of patrons in the gallery, tracked using the same methods the NSA uses to trace American phones. People around me own a lot of iPhones, and a lot of them are tapped into the Whitney Guest network. I am not, but my phone is still there on the screen, transmitting its quiet advances, making connections.

Oddly, this is one of the most spoken about parts of the exhibit in the first spate of reviews, yet the part that made people seem the least interested. This might indicate something about the quality of our attention. We communicate, in many ways, on multiple devices, all the time, but still there’s something we don’t receive, something that seems essential that we lost somewhere in the transmission. Our minds wander.

We don’t live collectively anymore. We exist as a social web of individual actors, highly mobile units of one. We’re atomized, whether we like it or not, and for all the social platforms we speak about we aren’t connected in the way that “connection” used to mean what it did, and so the challenges of communal discourse and collective action are infinitely more difficult than they were fifty years ago when you had to call people on telephones attached to tables and countertops and smashed out glass boxes in the street. It makes the stream of data on the screen, personally implicating you as you come into its orbit, not as much of a shock or a rupture as it might be. I’m not sure that Poitras intended for it to be a shock. She’s just pointing it out.

Included in the exhibit are documents recently released to Poitras in the ongoing lawsuit she’s filed against the U.S. government, and the inclusion of these documents is the other most spoken about part of Astro Noise. The documents reveal that Poitras was the target of a classified national security investigation conducted by the FBI and other intelligence agencies, which saw her searched and detained every time she crossed the U.S. border for a decade.

What are these documents doing? There is no call to action. There is no “Power to the People” message anywhere in the gallery. Power, it suggests, is the problem, and one there may not be a solution to.

In 1930 Andre Breton declared that “the simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd.” This was what so much political art in the twentieth century was interested in doing—not shooting blindly into crowds, exactly, but trying to dissolve the barrier between art and life. It was why so much art was confrontational, was invested in outright protest. But the efficacy of that kind of approach may no longer make as much sense for the current moment. Not because our general complicity in the cruelties of the world has lessened in any way, but because when we live in a world where beheadings are available for casual viewing on YouTube and the enormity of political crises has left none of us free of complicity, being exposed to those facts of life in art doesn’t read as shocking or revealing, so much as making the reveal seem like a depressing reiteration of something we already know. This is what we mean when we describe ourselves as “desensitized.” Exposing audiences to the reality of state sponsored drone strikes, of unilateral surveillance and subterfuge is fine, but it’s nothing compared to our general capacity to assimilate or shrug off the horrific realities of life. Certainly exposing audiences to these things guarantees neither catharsis nor redemption.

*

It’s not surprising, perhaps, that a work of art engaging with the war on terror and our personal complicity in the surveillance state might create a feeling of loneliness. It is political, but also personal, because it attests to the ways in which we experience the world as it is, and how we justify it to ourselves.

In the installation entitled Bed Down Location, strangers lie down together on a carpeted platform and look upward to the videos being projected on the ceiling. The videos show night skies over Yemen, Somalia and Pakistan, all countries where the US military flies drones. For the most part, the skies are indistinguishable from any other night sky. But when a daylight projection begins—shot at a military site in Nevada—drones are visible darting across the sky. The image cycles back to night, and you begin to notice that the stars seem to move strangely. They are night skies populated by unseen drones. Poitras makes you the protagonist of these scenarios. Lying on a platform with strangers beneath strange-looking skies you are not only intellectually but also emotionally engaged by the atomization of power, the anonymity of it and its vastness. It feels lonely.

Having feelings about a piece of art does not necessarily make anything happen. As Maggie Nelson observes in her collection of essays The Art of Cruelty, “focusing on the question of whether or not an image retains the capacity to produce a strong emotion sidesteps the problem that having a strong emotion is not the same thing as having an understanding, and neither is the same thing as taking an action.”

*

I will never get used to harsh winters. The way light and leaves turn gray and brown and the tips of my fingers ache in my pockets. When I moved to New York it was a winter very like this one. Although I felt more myself than I had really ever felt before, I didn’t know anyone and spent a lot of time on my own. I slipped in the snow because I didn’t know to wear the right shoes, my phone was message-less, and I met somebody but he went back to Chicago. I got lonely. I remember lying on the couch in my coat listening to the sounds of people moving about in other apartments. I remember the voices of a New Year’s Eve party carrying through the wall. I never found out who those people were. That is the risk of loneliness, and its attraction. Nothing can reach you. You can convince yourself that the events of the world will be unaffected by your actions, or lack thereof. That you can fight all you want, and you will lose.

A year before the winter I moved to New York, Laura Poitras was writing in her diary, “I’ve created my isolation, so they win. They always win.” This feels to me the most affecting thing about Astro Noise, a small reminder that this is art trying to reach you by exposing the depth of the loneliness that surrounded its production. Not pulling you out of the loneliness, not promising redemption or encouraging a solution. Just gesturing at feeling. Encouraging you to be if not full of fervor, at least not numb.

In her book The Lonely City, Olivia Laing makes the point that, regardless of how important it is to many people, art can’t do a lot of things. “It can’t bring the dead back to life, it can’t mend arguments between friends, or cure AIDS, or halt the pace of climate change. All the same, it does have some extraordinary functions, some odd negotiating ability between people, including people who never meet and yet who infiltrate and enrich each other’s lives. It does have a capacity to create intimacy.”

When I come out of the exhibit the sky is gray over the river and the Hoboken Terminal in New Jersey across the water. There’s a construction site down below and a yellow digger moving rubble, a jogger, someone in a jumpsuit picking up trash by the West Side Highway. A man in a white hoodie comes to stand by the window and then his girlfriend joins him. She wears jeans and ugg boots and has blonde highlights in her hair. He has her pose by the window, she juts out her hip, she smiles and he takes her picture. Two old women look out at the river. “Wow,” says one to the other. “Look at that. When I lived in the city this was garbage real estate.” A helicopter circles low over the Hudson.