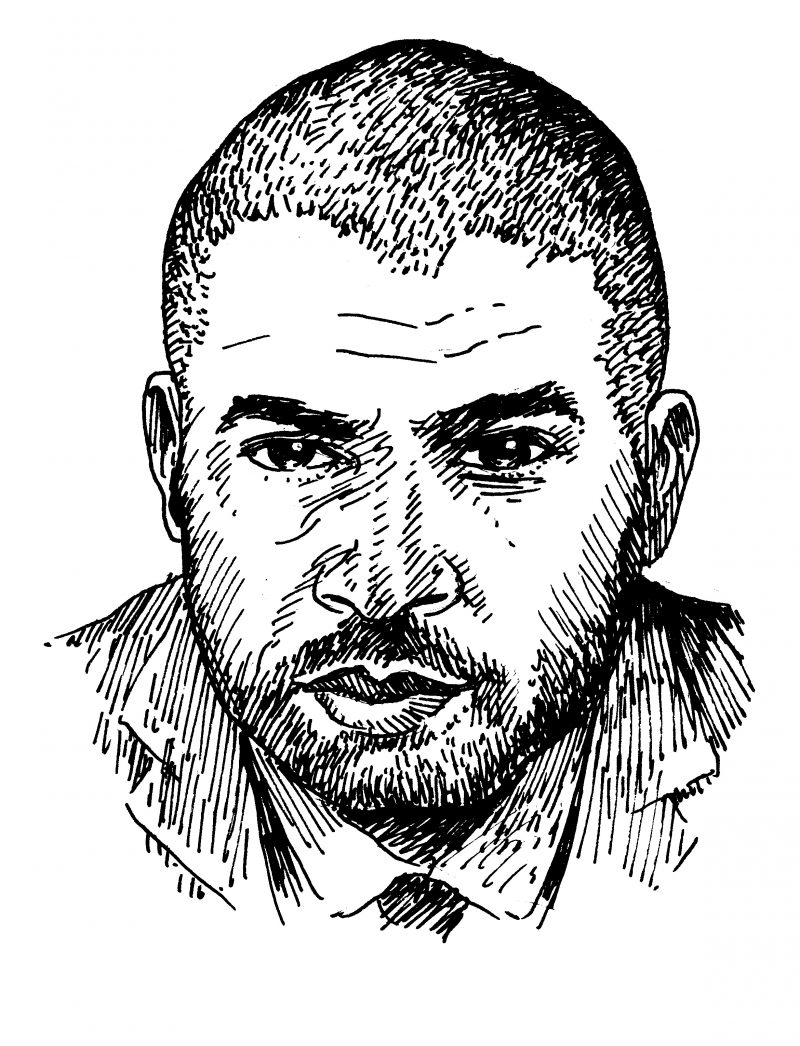

Jason Moran is cutting a wide path for jazz in the twenty-first century. He embraces tradition and courts innovation, joining the past and the future. He’s reinterpreted works by one of his musical forefathers, Thelonious Monk (whom he calls “the most important musician. Period.”), but he also regularly pushes the boundaries of improvisation, performing with dancers, filmmakers, painters, and writers. He’s astonishingly prolific, making records as a bandleader, soloist, guest artist, and with his longtime trio, the Bandwagon.

As an educator at the New England Conservatory and as a musical curator, he’s creating a new context for jazz. Recently, he created a concert series at the Park Avenue Armory, featuring musicians who exist at the edges of the mostly conservative jazz world, including Alvin Curran, Charlemagne Palestine, and Matana Roberts. In 2010, he won a MacArthur Fellowship for “genre-crossing performances.” In 2014, he was named the Kennedy Center’s artistic director for jazz, perhaps the most significant international title for a jazz musician. That same year, he scored his first film (Selma) and recently composed his first orchestral work, which premiered at the San Francisco Symphony in May 2018. Like Miles Davis did before him, Moran aims to influence the direction of music both through his musical language and the dynamic community with which he surrounds himself.

Moran also makes visual work. While jazz is not usually considered a visual medium, Moran merges its musical vocabulary with the fresh, experimental context of contemporary art. He’s spent much of his career collaborating with some of the most significant visual artists of the last half century, including Adrian Piper, Glenn Ligon, Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, Kara Walker, and Julie Mehretu. At the 2012 Whitney Biennial, he and his wife, opera singer Alicia Hall Moran, created a five-day hybrid performance of artistic disciples in a single space. At the 2015 Venice Biennale, he exhibited a sculptural re-creation of Harlem’s historic Savoy Ballroom stage. In May 2018, Moran presented his first solo museum exhibition at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, which included three re-created stages (including the Savoy’s) and a series of his charcoal drawings, which he makes by taping a piece of paper over the piano, covering his fingertips in charcoal, and playing.

I spoke with Moran in New York, a few days after he’d returned from a London performance with Joan Jonas, his longtime collaborator and one of the indisputable pioneers of performance art.

—Ross Simonini

I. “WHEN THE MUSICIAN STEPS OFF THE STAGE, WHAT DO THEY BECOME?”

THE BELIEVER: You’ve been working with Joan Jonas for about fourteen years. What’s the process of that collaboration?

JASON MORAN: Our relationship started...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in