For more than 150 years, Darwinism and its legacy have structured the Western imagination.

Consider the difference: walking in the woods 200 years ago, you’d likely have believed that everything you saw sprang full-formed, miraculous. Today, you know in your bones that those same woods are a scene in the midst of evolving: billions of years of gradual change before, and—human intervention notwithstanding—many more ahead. This idea is now embedded deep in the subconscious of our culture and our psyches.

We live in a teeming, seething world, but a structured one, at least in the realm of biology. Each species is privately progressing along its own developmental pathway.

Or so Western civilization has held since Darwin. But fifty years ago, a rebel scholar began to challenge this paternalistic, Victorian orthodoxy, and her ideas are just beginning to filter through to the mainstream.

Lynn Margulis was an American biologist, a towering intellect, and a true interdisciplinarian who enrolled at the University of Chicago at the age of fourteen and was briefly married to Carl Sagan. Her great gift was an ability to zoom in to the micro and, from it, extrapolate the macro. Studying microbes in this way, she solved the riddle of how life as we know it began.

In the late sixties, Margulis fixated on the cytoplasm of cells, then generally held to be just so much jelly. Following a hunch and some older, unproven research, she soon found, and proved, that the floaters in this cytoplasm are remnants of other species. Specifically, these fragments we all carry at our most elemental level are related to bacteria still found in the world today: Rickettsiales proteobacteria, in the case of animals, and cyanobacteria in plants.

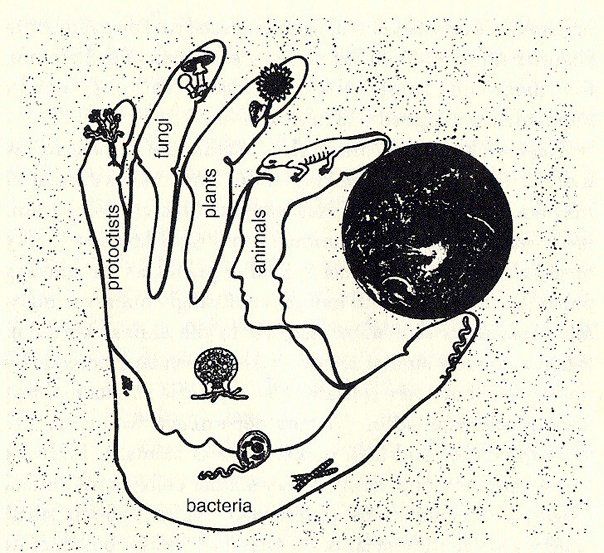

From here, she deduced the origins of all plant and animal life. Some 1.5 billion years ago, she concluded, a fat old early bacterium grabbed onto a swimming bacterium and fused with it, combining forces, and from that moment of opportunism was born the first ever cell with a nucleus—the type of cell that gave rise to all animals, plants, fungi, algae, and protists.

She discovered that life as we know it originated through symbiosis between two different types of organism. Down to the very cellular level, the story of our lives is a story of mutual dependence, of fusion, synergy, and collaboration, in which microbes aren’t harmful germs, but the precondition of existence. This theory of symbiogenesis is now widely accepted.

But Margulis didn’t stop there. The Darwinian ideal that has ruled so rigidly and for so long in biology and beyond holds that species evolve when individual variations arise...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in