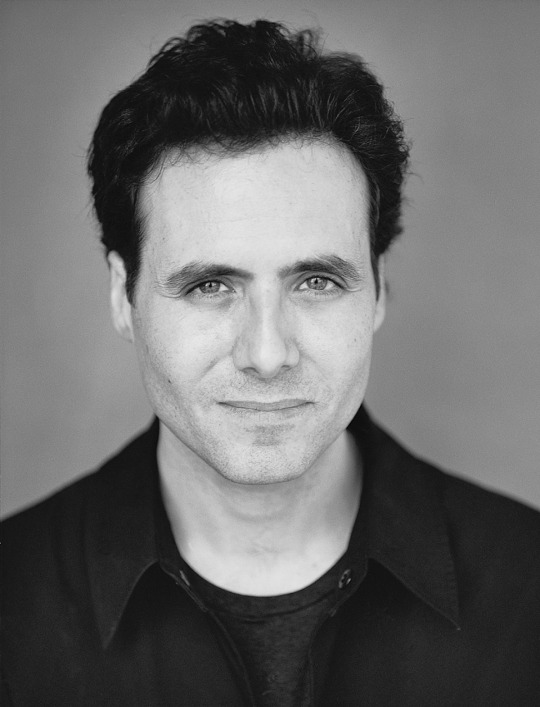

Photograph of David Lipsky by Shaun McDowell

An Interview with David Lipsky

David and David. Two strangers with a lot in common took a five-day road trip in 1996, a trip that wound up becoming as public as it was private, that travelled as far into being a writer as into being a person. “I want to be able to try and shape and manage the impression of me that’s coming across,” David Foster Wallace told his interviewer, Rolling Stone’s David Lipsky. “I’m hanging out with you, I can’t even tell whether I like you or not, because I’m too worried about whether you like me…. How do you learn to do this stuff? Did you go to interviewing school?”

Lipsky had to fight to convince his editor about the assignment, then had to win Wallace’s interest and trust. The story, published in 2008, received the 2009 National Magazine Award. The book, Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself—containing the entire trip—followed in 2010, a Times bestseller and NPR Best Book of the Year. Which lead to 2015’s The End of the Tour, with Lipsky portrayed by an awed and avid Jesse Eisenberg, and Jason Segel masterfully playing David Wallace.

“Why are we,” Wallace asks in the movie and book, “and by ‘we’ I mean people like you and me: mostly white, upper middle class or upper class, obscenely well educated, doing really interesting jobs, sitting in really expensive chairs, watching the best, you know, watching the most sophisticated electronic equipment money can buy—why do we feel empty and unhappy?”

Lipsky collected and sorted Wallace’s testimony during the rise of grunge and the everything-online generation. (“We’re gonna have to build some machinery, inside our guts, to help us deal with this. Because it’s gonna get easier and easier, and more and more convenient, and more and more pleasurable, to be alone with images on a screen,” Wallace says, “given to us by people who do not love us but want our money.”) In the book, the young writers discourse on junk food, junk movies, good books, bad relationships, loneliness, fame, and addiction.

Lipsky is a professor of creative writing at New York University and a powerful voice in American fiction (Three Thousand Dollars, The Art Fair) and nonfiction (Although of Course, Absolutely American, the forthcoming Parrot and the Igloo). Disproving the axiom that journalists make terrible interviews, Lipsky responded to my questions with enthusiasm and curiosity. We talked about Gabriel García Márquez’s genre-bending The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor—appearing nine years before Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood warped the genre entirely. Also Roberto Bolaño, Joan Didion, Pauline Kael, and Jorge Luis Borges, who Lipsky read while studying at Brown University.

—Laura Ventura

THE BELIEVER: What are your impressions of The End of the Tour? Did you talk to the crew before or during the process? Did any of Wallace’s relatives contact you?

DAVID LIPSKY: I thought they were true to David Wallace’s words in the book—which was very important to me, and something I talked a lot about with the director and actors. I haven’t been contacted by any members of Wallace’s family. They did contact me about the book, and were kind and wonderfully helpful.

BLVR: To what extent do you feel David’s influence in your work?

DL: He always has, as he’s influenced every smart reader and writer since the mid-90s. His basic advice—stay awake, as he puts it in his political essay—is the only advice that really matters for writing, but there are a hundred bits of smaller advice. Vary your voices; look to your modifiers; be willing to personalize. That’s the gift writing gives you; you get to ride for a certain number of pages in someone else’s brain. Wallace reminds you to make it your brain; to listen to how you experience people and the world. That that’s part of what your ride offers.

BLVR: Why wasn’t the interview published by Rolling Stone until 2008?

DL: When I came back from Illinois, Jann Wenner reassigned me to an emergency story: a spike in heroin use. He wanted me to live with needle addicts in Seattle. It took about six weeks; when I was back from the Northwest it was May, Infinite Jest had come out in February. Ancient history for a magazine.

BLVR: Wallace had a TV addiction, before streaming existed. People now spend weekends watching TV shows, are these two overdoses similar?

DL: Yes! [Laughter] Streaming lets everyone be like Ken Erdedy, without waiting for the woman who said she’d come. [Edredy is a character in the novel’s harrowing, funny second chapter.] I just spent twelve hours with House of Cards: a full Saturday. Bliss. Compared to now, Wallace is a teetotaler.

BLVR: Wallace, throughout your book, talks about being humble—courtesy and kindness, and his will not to hurt people. Do you find this often in the intellectual world?

DL: I don’t think kindness, humility and courtesy characterize the intellectual life anywhere on the planet. The not-hurting people thing about Wallace’s work is a bit of a received myth—there’s plenty of cruelty in his fiction and essays, moments of acute impatience, of a thrilling ungenerosity. He’s being true to the inside of the skull, and all kinds of things flower there.

But in general, there’s a cuttingness and slashingness to the intellectual life that David was a respite from: he wrote one mean essay about Updike, but otherwise was intellectually generous. He characterized literary New York as the hiss of egos in various stages of inflation and deflation.

BLVR: Do nonfiction authors still have to prove that this genre can become literature?

DL: If anything, Wallace is the proof, and sometimes people have to be talked into picking up Infinite Jest. It’s a fast novel, but there’s a lot of it. And people look at it as a mountain they’re being asked to climb without the hiking gear of a classroom and assignments. Capote’s work—the stuff that still lasts—is his journalism. The long snark on Marlon Brando. The Clutters. With Hemingway, it’s A Moveable Feast. Joan Didion’s lasting stuff all stars Joan Didion. And then at the opposite end, there’s someone like Pauline Kael, who never wrote anything but crit. She gave us a prose style, a certain way of punctuating, and a great brilliance. Here she is on Joan Didion. “The smoke of creation rises from those dry-ice sentences of hers.” A beautiful thought is a beautiful thought, no matter what the sign above the shelf where you encounter it.

But yes: I think there’s been kind of a renaissance of nonfiction—four decades, five. People don’t talk about it. Even if it’s what they read. It’s kind of where TV was fifteen years ago. Not quite respectable.

You feel bad, as a reader, for not doing the work of animating an untrue situation with the truth of your interest. Just the way we felt bad a decade and a half ago for not getting off the couch and sloping off to a movie theatre. But I think that’s changing: the memoir thing—a kind of halfway form—is changing it.

BLVR: You read a lot of Borges when you were at Brown, if I’m not mistaken?

DL: You’re right—and then especially in grad school with John Barth, who David was a great fan of. Borges is an astonishing figure. With his great, strange insight, from “The Approach to Al-Mu’tasim,” that you could write the review of the novel instead of the actual novel. A lovely insight, his combo of the literary essay on non-existent subjects and literature itself. Amusingly, Nabokov had the same insight, in a novel he wrote around the same time, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight (1941). Nabokov’s chapter on the novels Sebastian Knight wrote allowed him to summarize half a career’s worth of plots and notions.

BLVR: Can you teach someone how to be a writer?

DL: I think you can. Many of our best writers come out of the programs. George Saunders, Lorrie Moore, Karen Russell, and of course David Wallace. It’s the two years of focus: like training for the Olympics, knowing you’ve got twenty-four months on a kind of team that’s practicing skills. The students come in with talent, and the profs try to sharpen it, bring it out. I’ll assign Jhumpa Lahiri, Nabokov, Borges, Alice Munro, and we’ll look at it the way film students check something by Scorcese or Jim Cameron: How was it put together? Why should film students have all the fun?

BLVR: In which ways do journalists and nonfiction authors feel Truman Capote’s influence? Is it still so vibrant? Do you think that if In Cold Blood wasn’t published, chronicling and nonfiction would have still managed to make its way in media and books?

DL: I think so, don’t you? There were enough posts along the way: Hemingway wrote “Che ti dice la Patria?” in 1927—that was the original title, “Italy—1927”—and it’s just nonfiction: pre-fascist Italy. Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina—both had their birth in (local) news stories.

What Capote had developed is a style in excess of his material: it was greater than Other Voices, Other Rooms or Breakfast at Tiffany’s. He needed something to shine it on. And the idea of applying the full fury of a beautiful prose like that to a news story, at complete length and force, was exciting. It hasn’t been entirely followed up on: But in someone like Knausgaard, it’s being a little followed up. One objection is that with Capote in between, you had Proust doing it in the previous century. Knut Hamsen, too. People were reaching for it—the amazing thing was Capote somehow writing a first-person style, a first-person sensibility, in a third-person story.

BLVR: You spent a year chronicling the lives of at-risk gay and lesbian teenagers [Lipsky’s piece won a 1999 GLAAD Award] and then time in West Point. Do you sometimes forget you are a witness? After some time there you start to develop relationships with the people you interview. How did you deal with that?

DL: With West Point, yes, at times. The adult officers sometimes did, too. They’d see me after hours and say, “Get back to barracks, cadet.” They forgot why I was there. And with the teenagers, a very strong identification, because in the late nineties their lives were so stark: you wanted to help. And I wouldn’t want to deal with it in any way except feeling it. It’s a fascinating thing to feel. Capote, of course, took that to an extreme. But it’s one of the things we read nonfiction for—and one of the things you write it for, too. That vacation in another sort of life. Capote was so locked into his particular style of prose and thought, it must have been—since Dick Perry was so much the other—a tremendous relief.

BLVR: You show in your book that the market often pushes writers into road trips and book tours. Is that still so? How do you feel about it?

DL: I keep reading and hearing those tours are gone, though you still go on them. In what Wallace would’ve called a po-mo development, I went on one for the book about his road trip. I think it’s trying to redress a thing about writing: you can love someone’s words and mind and not see them. Movies, music, TV: you see the people you love. With books, you don’t get that so much, and I think it was a way to both glamorize the field and also provide that service. I have loved Infinite Jest: now let’s see how this person moves and looks, let’s see them in the process of seeing this world they so well understand. When someone experiences so quickly, we want to get to watch them doing it.

BLVR: Do you have any impression of Latin American nonfiction authors writing at the present? We have a sort of nonfiction wave linked together thanks to Gabriel García Márquez Foundation. How is American nonfiction different from Latin American nonfiction?

DL: I don’t know Latin nonfiction well enough: Borges’—the nonfiction I know best—is so donnish and speculative and playful. Owlish, is the British word. “Three Versions of Judas” or his Shaw piece or the one about Pascal’s sphere. They’re fireworks of learning, but a model no one has really followed; they have a quality of dustiness, like rubbing between your fingers the grains on top of a wall. Those grains are the little crumbles of civilization that Borges liked to be playful with. Dry in a terrifying way. And of course Márquez’s first work was the The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor—nine years before In Cold Blood. A good idea will get expressed in a number of places simultaneously. It’s the kind of thought that would have pleased Borges.

I do know that Bolaño has been like a thunderclap for American writers-in-training. His rigor and looseness at once. That for young writers here, there’ll be excitement about these two peaks, Wallace at one end, Bolaño at the other, with the attempt made to string themselves somewhere in the middle.

This interview first appeared in La Nacion.