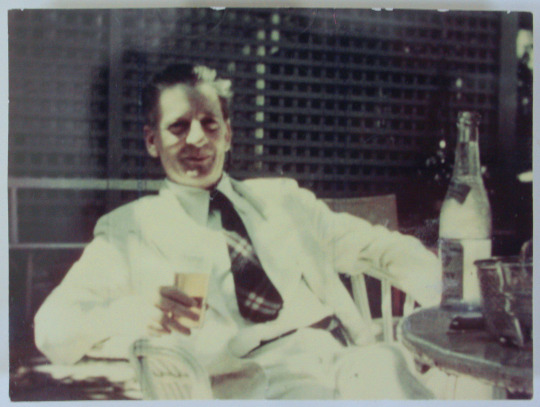

Maxwell Perkins likely taken by the author’s grandmother—Corinne Brooks Cornish—around 1940.

Joel Rice on Maxwell Perkins

You have no idea how much I wish Baba were still alive, just so that I could interview her about Maxwell Perkins.

Recently a movie about the shamanic editor—Genius, based on the 1978 biography Editor of Genius by A. Scott Berg—has been sharpening this already keenly felt sense of regret.

(Maxwell Perkins was, of course, an editor. But the term is utterly insufficient. He was the mystical man who first published Hemingway, whipped The Great Gatsby into shape, and wrestled Thomas Wolfe’s manuscript for Look Homeward, Angel into manageable submission.)

The fixation, I believe, is forgivable.

Mr. Berg himself understood my grandmother to be a valuable historical resource, kindly including Corinne Brooks Cornish—better known to her grandkids as Baba—in his acknowledgements.

*

Taciturn even by a previous generation’s Puritanical standards, she was not an easy interview.

I know because I asked her about him, once. It was during dinner one night in 1997 that I, nineteen and back from college, had the audacity to pose this impertinent question: “What was life like at the Perkins’?”

There was a lot she could have said in response.

Her freshman year at Vassar—1937—she roomed with Jane Perkins (the editor’s daughter) and thus, on the Poughkeepsie campus, a lifelong friendship was forged. In some ways the pairing was quite natural. Both the girls came from literary families. Alden Brooks—Baba’s father, my great-grandfather—was a novelist and serious chronicler of his martial experience. (Hemingway included him in the collection Men At War: The Best War Stories of All Time.) Like Perkins, he’d gone to Harvard, graduating in 1905. (Perkins graduated in 1907.)

Alden Brooks—in Hollywood, Maryland—was an ardent “Shakespeare denier” and managed to rally Maxwell Perkins to the quixotic cause.

Soon, Baba became a frequent dinner guest—immediately smitten by the Perkins’ less formal protocol. When her own family ate together, Alden would demand to know what one had done during the day. (A theme: She didn’t like talking during dinner.) In the Perkins household the daughters were allowed to come to dinner with a book, and read in peace. To Baba this was heaven. (Like the old woman in Robert Lowell’s poem “The Skunk Hour” she always seemed to be “thirsting for the hierarchic privacy of Queen Victoria’s century.”) Not one to embellish, Baba reliably recalled being present when Maxwell Perkins busted out the famous letter from Thomas Wolfe—in which the author makes amends with the editor right before dying.

After Vassar, she lived with Jane in a Manhattan apartment.

And these ancestral lines intersect on a still stranger...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in