Format: “A-side” of a digital single; Track Length: 6:19; Price: $4; Record Label: Ghostly; Country of Origin: Australia; Pronunciation Key: “Hate Rock”; Number of Publicists I Emailed Before Receiving a Download Link: Six; Representative Lyric: “Even with your soft obsession / It’s not enough attention for me / Even with another mention / You should have made a difference by now”

Central Question: How has social media changed the love song?

One of the more memorable moments from John Lennon’s famous Playboy interview with David Sheff comes when he explains the inspiration behind the Beatles song “No Reply”: “I had the image of walking down the street and seeing [someone] silhouetted in the window and not answering the phone,” he says. “Although I have never called a girl on the phone in my life! Because phones weren’t part of the English child’s life.”

Weirdly, this is not the only time Lennon felt the need to justify telephone references in early Beatles songs. He also said that “All I’ve Got to Do”, another early Beatles song that mentions the phone, was written “specifically for the American market.” And again, that “the idea of calling a girl on the telephone was unthinkable to a British youth in the 1960s.”

Imagining a world before pop songs mentioned the telephone is almost as difficult as imagining a world before pop music altogether. That calling someone was once a rarefied privilege of suburban American youth is all the more baffling when you consider that “the telephone” is one of the pop canon’s most prominent thematic hooks. This trend largely originated in the late ’50s and early ’60s (“Chantilly Lace”; the aforementioned Beatles songs), but technically begun much earlier: the first pop song to make mention of the telephone is the Tin Pan Alley rag “Hello! Ma Baby”, which is about a long-distance relationship between two people who have never seen each other. The song was written in 1899, when less than 10% of American families owned telephones.

The best songs about telephones were arguably produced in the ’70s and ’80s, with songs like The Nerves’ “Hanging on the Telephone” (which was later covered and made popular by Blondie), New Edition’s “Mr. Telephone Man”, and Electric Light Orchestra’s “Telephone Line”, just to name a few. There are newer pop songs about the telephone, too, like Adele’s “Hello” and Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe”. But this motif is eroding into an anachronistic cliché, since actually talking on the telephone is becoming less and less common among the demographic that consumes pop music. For most of us, phones are a cumbersome intermediary that will just have to do until we can text and tweet from our brains. Traditional phone calls are reserved for important conversations and scheduling doctors’ appointments; you’re out of your mind if you call someone on the phone before you even meet them.

The trials and tribulations of communicating in the digital age should be fodder for beautiful, modern pop music. Hitting a busy signal repeatedly is certainly as excruciating as a “seen” DM that goes unanswered for hours, or getting butterflies when your phone vibrates only to realize that it’s just an email from Domino’s. Where are the pop songs about this? Instead we have a Chris Brown song called “Twitter”, which employs one of the worst lyrical conceits in the history of popular music (“Follow me like Twitter,” etc.) and the Chainsmokers’ “#SELFIE” which reeks of ageist, sexist technophobia (“’Can you guys help me pick a filter? / I don’t know if I should go with XX Pro or Valencia.’”) There have been more accurate portrayals, to be sure, but nothing that feels complete: Katy Perry’s “Save As Draft” is a rambling mess with a few clever if perfunctory Twitter references, and Drake’s “Hotline Bling” is essentially just a “U Up?” text extrapolated to several unnecessary verses.

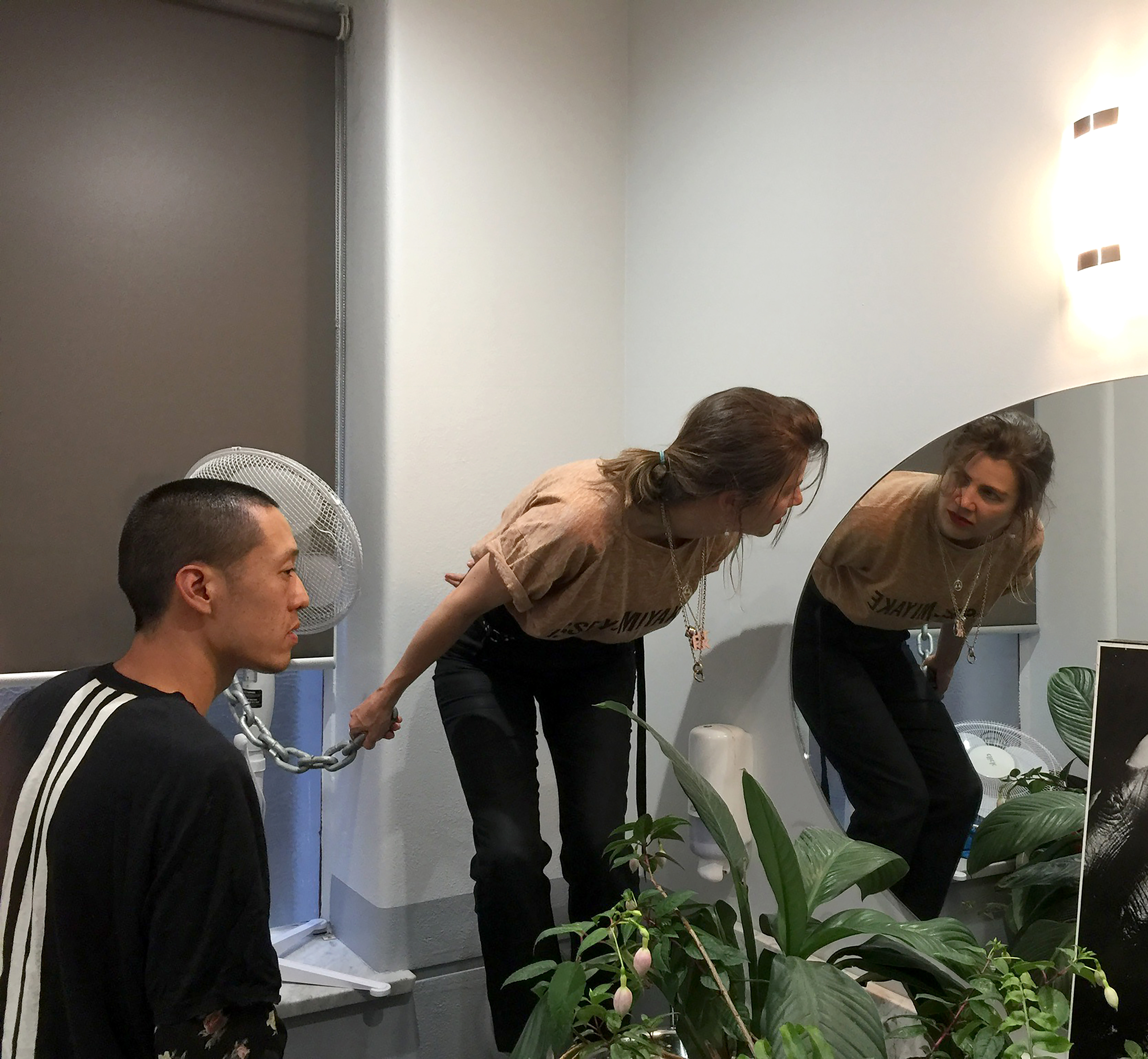

The lyrics to “Mentions”, the first new song from Melbourne synth-rock band HTRK in four years, depict social media more accurately than any of the songs I just mentioned. In the song, HTRK’s vocalist Joninne Standish cools to real-life romance once she discovers it pales in comparison to social media’s bottomless drip feed of instant gratification. “The touch of your hand to my face / And the way you’re talkin’ softly / It’s not enough attention for me.” Standish croons over a hypnotic beat and ice-cavern guitars. This juxtaposition of futuristic-sounding music with techno-resistant sentiment brings to mind “Video Killed The Radio Star”—except that song ultimately deals in cheeky nostalgia, not utter despair.

“Mentions” would make the Boomers, Generation Xers, and older Millennials critical of social media feel vindicated. And parts of this of premise are certainly indisputable: social media probably has limited our desire for “real,” physical intimacy, but its benefits—even within the realm of romance—are obvious and innumerable.

I think back to literally every relationship I’ve been in, and they were all either formed on—or greatly facilitated by—social media. There was a point in the not-too-distant past when “falling in love” over the internet was deemed fantastical and illegitimate by adults. At the height of my message board-dwelling days in the mid-00s, online dating was frowned upon; it signified desperation and was solely the domain of lonely nerds. But the nerds won, and online dating is something everyone participates in now.

“Mentions” is a deft portrayal of love in the social media age at its absolute worst: when love becomes so intoxicating and all-consuming that you forget how to function in the real world. This happens, and it’s a pathology that social media does seem especially eager to expedite. But you can also transpose this scenario to any other form of non-physical contact. “Mentions”’ narrator is not unlike Jeff Lynne in “Telephone Line”—an obsessive mess who has been calling the same person for days to no avail. (It makes perfect sense that one of Lynne’s most impassioned performances ever recorded is when he sings the line, “Let it ring forever more.”)

“Mentions” is poignant and relatable, but it’s only one side of the coin. There’s still a dearth of songs in the pop canon about how beautiful and exciting love in the social media age can be: the flirtatious exchange of memes at 3AM, the gut-wrenchingly ambiguous text conversations, the simple but highly symbolic act of “liking” a crush’s mundane Instagram photo from several weeks ago. Maybe contemporary songwriters are worried about seeming overly topical—but as a 24-year old John Lennon understood, that’s the key to connecting with the masses. Modern love deserves a new soundtrack—or at the very least, a better song than “#SELFIE”.