I am obliged to perform in complete darkness

operations of great delicacy

on my self.

—John Berryman, Dream Song #67

The poet John Berryman once said, “I do strongly feel that among the greatest pieces of luck for high achievement is ordeal… My idea is this: the artist is extremely lucky who is presented with the worst possible ordeal which will not actually kill him. At that point, he’s in business.”

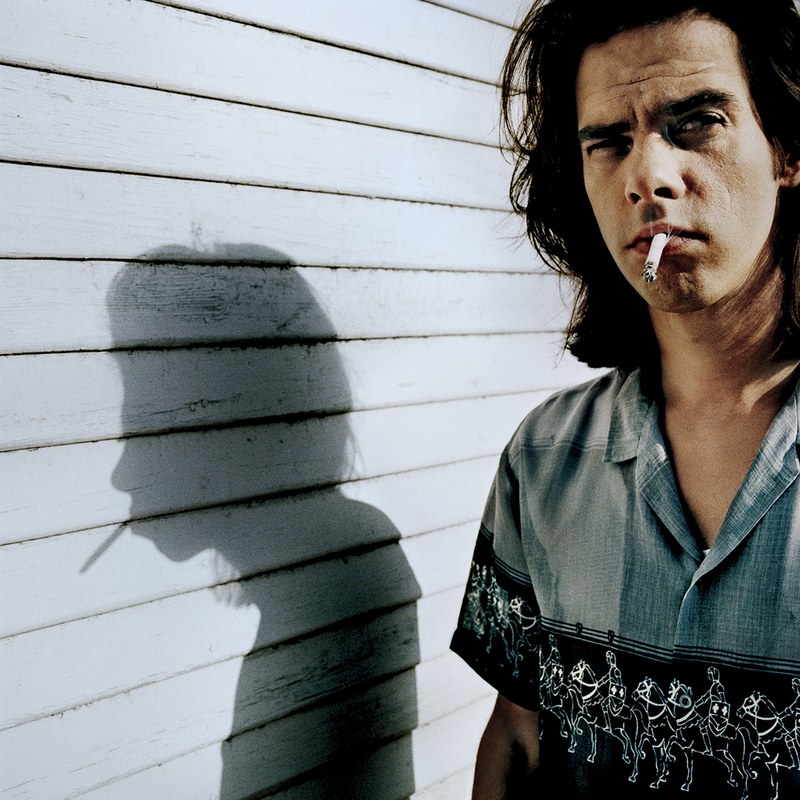

The musician Nick Cave has often referred to John Berryman as the most important influence on his writing; Berryman the poet who created, in his friend Robert Lowell’s words, a “Pierrot’s universe… more tearful and funny than we can easily bear” out of his own “extreme luck”—alcoholism, the scarring childhood trauma of his father’s suicide, a loss of and search for faith—latterly through the person of Henry, “not the poet, not me.” Henry, the central figure, of Berryman’s Dream Songs, is articulate with pain, his syntax tortured and broken, his despair and wit tragic and abiding. The poems in which he speaks seem as necessary to their poet’s survival as any of their century, a way for Berryman of coping until they weren’t, anymore. “Poetry is a terminal activity, taking place out near the end of things,” Berryman said elsewhere, “And it aims—never mind either communication or expression—at the reformation of the poet, as prayer does.”

Cave parts ways with Berryman when it comes to the idea of suffering as a stirring, creative force. In the 2016 documentary One More Time With Feeling Cave said, “Trauma is extremely damaging to the creative process,” it leaves “no imaginative room.” The notion of self-reformation, of song as a form of prayer, is familiar to Cave, and has been throughout a career which began in earnest amid the chaos and malevolence of The Birthday Party in the late 1970s. Out of that lawless hyperactivity Cave has become a literate, prolific and restless songwriter, an anthology of styles and contradiction with a back catalogue taking in narratives of revenge, yearning and caustic disillusion, all fleshed out, stabilized, sonically driven on and interrupted by the brilliance of his band. Cave has stolen elements and imagery from a number of traditions—the Blues’s deadpan woe, country’s three-chords-and-the-truth storytelling—reinterpreted and taken liberties with them, to create a blood-hued universe of good and evil. Cave’s cosmology requires a God and a Devil, and is often narrated by a Cave-like figure—somewhat Henry-ish in his mischief, bawdiness and confession—who roams, howls, and desires. Rather than settling over the years into a stylistic rut, churning out new iterations of an agreed-upon formula, Cave has remained twitchy and malcontent.

Cave suffered the worst possible ordeal...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in