This is the first installment of a new series in which Believer staff make note of things they like. The things recommended will come from all corners of this gorgeous and oversaturated culturescape. They might be timely or they might not. They might feature accounts of hand kinks or they might not (this one does). If you are interested in sharing things with us that you think we will like, please mail them to:

The Believer Magazine

4505 S. Maryland Parkway

Box 455085

Las Vegas, NV 89154

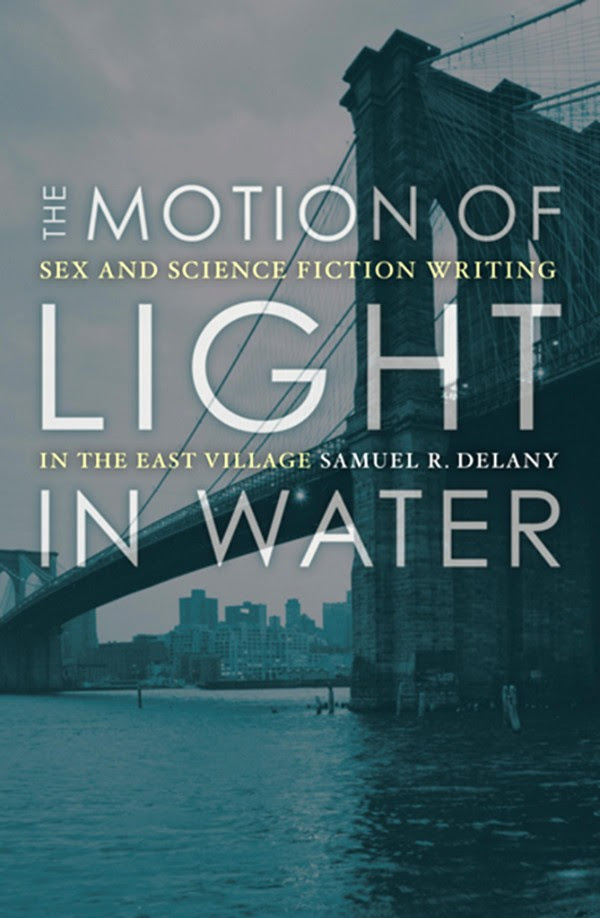

The Motion of Light in Water

Samuel Delany’s autobiography

W.H. Auden bit his nails, and Samuel Delany would know. Delany, who once had the poet and his partner over for shrimp curry, has a thing for hands—a kink not just sexual but artistic, expressed all over the writer’s prolific output of fiction. Broken and cracked hands show up in many of the science-fiction giant’s twenty novels, and a key to navigating Delany’s particular prehensile map can be found in an early autobiography, The Motion of the Light in Water. Noted there are the “work-hardened hands” of a construction worker he blows by the Christopher Street waterfront; “the soap-white hands” of his then-wife, poet Marilyn Hacker; and his father’s “long hand with its slightly clubbed fingers.”

His father, Delany writes, died of lung cancer in 1958, when he was seventeen. But the date’s a lie, a sleight of hand on the part of the writer’s unconscious that Delany himself only discovered when two scholars from Pennsylvania later put together a chronology of his life. His father actually died in 1960, when he was eighteen. The discrepancy between fact and memory is at the core of The Motion and their interplay is much of what makes the book perceptive and rich. Delany does write about his time at Bronx Science, about when he worked as a stock clerk at Barnes and Noble, his stint in the village as a minor folk guitarist. He tells anecdotes about having almost opened for Bob Dylan, going to see a Happening of Allan Kaprow’s, ditching New York to fish in the Gulf Coast with a lover named Bob. He writes about his months-long live-in threesome with Bob and Marilyn, his open-marriage and sexuality, and the anonymous men he’d regularly fuck. But more than just recount details, The Motion emphasizes the unreliability of memory. It’s a book that shows how fathers die both when you’re eighteen, and again when you’re seventeen, too.

Put another way: Delany refers to a system he had for writing in a notebook where on one side, he’d write fiction. When he wanted to journal, he’d flip...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in