It’s sometimes easy to forget that our technologically complex world wasn’t created out of whole cloth. Or that it wasn’t always here. Without an awareness of the past, “the sense of time falls in upon itself,” writes Lewis Lapham, “collapsing like an accordion into the evangelical present.”

“Vintage Tech,” a column by B. Alexandra Szerlip, will examine some of the under-the-radar stories, personalities and techniques that inform our 21st century lives.

Americans “have no time—so they say!” observed a Frenchman traveling stateside in the 1890s. “They work so hard—so they must affirm! Competition is so bitter. ‘We must hustle,’ ‘we must hurry up.’ Capital phrase, that: Hurry Up.”

“In the West,” observed British anthropologist Stephen Hugh-Jones more than half a century later, “time is like gold. You save it, you lose it, you waste it, or you don’t have enough of it.” The Barasana, an Amazonian tribe Hugh-Jones devoted much of his career to, have no word for time.

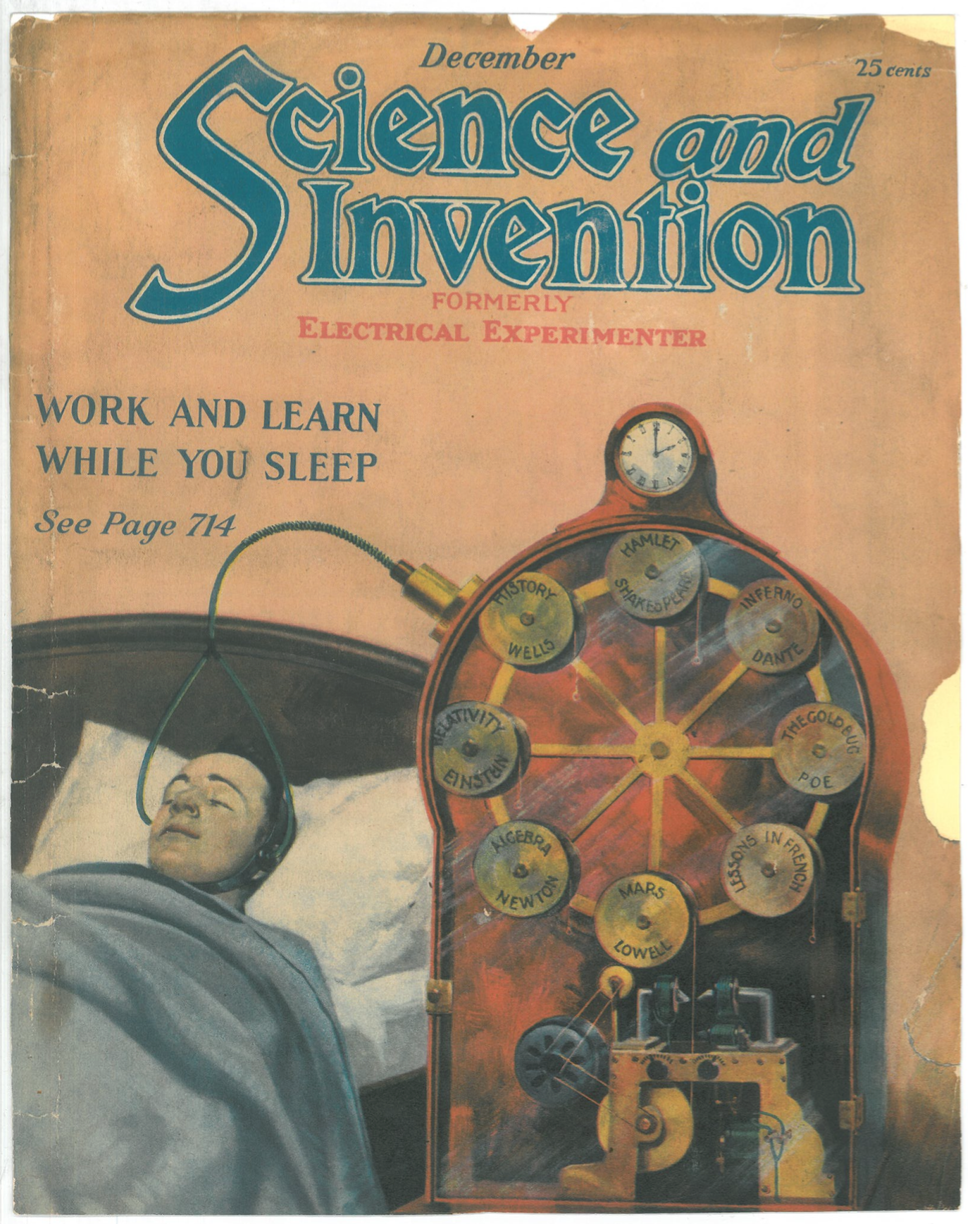

Not surprising, then, that the notion of Sleep Learning first surfaced in the New World. In New York City to be exact.

It’s also not surprising that it surfaced when it did. Having emerged relatively unscathed from the First World War, Americans were in more of a hurry than ever. Speed was all. Thanks to mass production, there was ‘convenience,’ ‘streamlining’ and ‘labor-saving’ at every turn. Tea bags and instant coffee. Throwaway razor blades and disposable condoms. Motor cars, telephones, and airplanes. Artists were busy deconstructing time into slices and jags, scientists into atoms and quasars. Even the Grim Reaper was adapting to the new century, with heart attacks (a quicker exit) displacing tuberculosis.

All the more reason to “dream up” ways to convert “lost” nocturnal hours into “productive” use. Given a lifetime of, say, seventy-five years, at an average of eight hours sleep per night, that’s 219,000 hours, or 9,125 days, or a quarter century “wasted.” A third of one’s life! And that’s not counting the extended sleeping habits of babies, children and teenagers.

Workaholic Thomas Edison considered sleep “an absurdity, a bad habit,” claiming he got by very nicely on three hours a night. “Sleep, those little slices of death,” complained master-of-darkness Edgar Allan Poe. echoing a popular 19th century paradigm. “How I loathe them.” Thanatos was, after all, Hypnos’s brother.

Following the 1922 publication of the hugely popular Self-Mastery Through Conscious Autosuggestion (“Day by Day, in Every Way, I’m Getting Better and Better”), the brainchild of French psychotherapist Emile Coue, self-improvement was all the rage, laying the groundwork for Dale Carnegie’s endlessly reissued mega-bestseller How to Win Friends & Influence People (first released in 1936, it proved a...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in