“I’ll tell you this, lad: A tattoo says more of a fellow looking at it than it can do of the man who’s got it on his back.”

—Sarah Hall, The Electric Michelangelo

“It’s only his outside; a man can be honest in any sort of skin.”

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

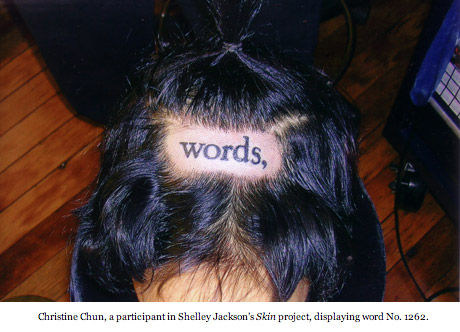

In 2003, the author Shelley Jackson announced that she would publish a 2,095-word short story called “Skin” on participants who agree to be tattooed with randomly assigned words from her text. The tattooees alone will read the story, which will be complete when the last commissioned word is inscribed on its bearer, sometime in the next few years. It will not be published on paper. Jackson asks applicants (she has many more than she can use) to read her novel, The Melancholy of Anatomy, to ensure that they like her writing before committing to a word, because “Skin” is what she calls a “hidden track” (in the pop-music sense) of the book; both explore the relationship between words and the body.

Jackson’s project, commissioned by Cabinet magazine, is a dramatic act of literary deconstruction—it pushes her words off the printed page onto the living body, marrying the reader and the text, the symbol and the narrative, not to mention visual art and fiction. Not surprisingly, her volunteers are both students and professors of literature, as well as artists, graphic designers and typographers. She also has mother-daughter teams, friends who want to become a phrase or a sentence, a private investigator, a zookeeper, and a specialist in glaciers. One participant is a book collector who saw the project as an opportunity to collect a rare manuscript. Another liked the notion of “a text written on bodies and the idea that the text would encounter erasure with death and time.”

Subversive as it is, “Skin” is rooted in a rich tradition of tattoo symbolism in American literature. We have Hawthorne and Melville to thank for drafting the dual designs—one personal and iconic, the other cultural and narrative—that have shaped tattoo imagery in American fiction. The Scarlet Letter (1850) and Moby-Dick (1851), those twin towers of prototypical symbolic lit, were published just as marked bodies began landing on the shores of American consciousness, soon after tattooed oddities and tattoo artists began plying their trade on the East Coast, and immediately before our nation’s first tattooed white woman, Olive Oatman, was released in California after four years’ captivity with Mojave Indians. Oatman was “repatriated” (probably against her will) in 1856 and resurfaced wearing a tribal tattoo on her chin, which riveted the American public.1

*

A Victorian savage was something to behold, and her tattoo worked its magic—for better and worse—much as Hester Prynne’s A did: it was a symbol of crossed boundaries and forbidden knowledge, and it carried no remorse.2

While Melville gave us a kindly cannibal—Queequeg—with a full cosmological treatise inscribed on his body (“a wondrous work in one volume,” penned by a seer) Hawthorne created a haughty “figure of perfect elegance” wearing a single letter, an emblem of shame converted to a badge of self-determination. For practical purposes, the letter, embroidered though it was on Hester’s dress, was a tattoo: she made it permanent by wearing it even beyond her prison term (“it is too deeply branded,” she explained), and it matched that of her co-adulterer, Dimmesdale, whose mark was more explicitly “imprinted in the flesh.”

Both Queequeg and Hester were exotics—she, a sexual renegade within American culture, he, an adventurer from without—but while Queequeg didn’t understand his own tattoos (they contained “mysteries not even himself could read”), Hester’s A denoted emotional ripening and self-knowledge, something new to Victorian women—or at least newly articulated in literature. And though the first significant American literary tattoo graced a man,3 tattoo symbolism has for a century and a half since been used most on female characters and, in recent years, almost exclusively in the hands of women authors. As a mark of women’s true selves (hidden, damaged, or imprisoned though they may be) the tattoo perfectly distills an eternal feminine theme: the resolution of the soul and mind with the body.

*

The writer Elizabeth Stoddard, who knew Hawthorne personally, ran with his branding paradigm in The Morgesons (1862), an underrated novel that brought to life a flinty female protagonist, Cassandra Morgeson, with sexual confidence and intellectual chutzpah to boot. Like Hester, Cassandra is an unrepentant adulterer; her married lover dies next to her in a carriage accident from which she emerges with “thread-like scars” on her cheek that serve, for the remainder of the book, as a reminder of a life lived without compromise. She even claims she got them “in battle.”

If it seems like a stretch to read these scars as tattoos, consider Cassandra’s response to her headstrong friend, Helen, who (in a radical act for her day) gets her fiancé’s initials tattooed in a bracelet on her arm:

“How could you consent to have your arm so defaced?” I [Cassandra] asked.

Her eyes flashed as she replied that she had not looked upon the mark in that light before.

“We may all be tattooed,” said Mr. Somers.

“I am,” I thought.

In fact, she wasn’t yet; this incident happens just before her accident. Cassandra had yet to become the one literally “defaced” by her scars, consenting to her own defilement by having an affair with a married man. But later, when a friend stares at the scars, she points to them and confirms, “tattooed still.” Cassandra’s battle wounds are the result of fearless free will, by contrast to Helen’s tattoo, analogous to a “Property of” biker tattoo: well-educated and willful, she abandons her ambition, gets engaged, and once married, tells Cassandra, “Marriage puts an end to the wisdom of women; they need it no longer.”

Stoddard applauds her unruly protagonist and rewards her, in the end, with a fitting partner—a suave, sauntering man who has also taken risks (to define himself apart from his shallow family). His response to her scars proves his worthiness. “I am yours, as I have been, since the night I asked you ‘How came those scars?’” he tells her in a letter. “Did you guess that I read your story?”

Scars as stories. Tattoos as symbols. Personal history manifested physically, in marks that can’t be hidden. Though it was a coincidence that Hester Prynne sprang to life a year before the tattooed Olive Oatman was taken hostage by Indians, Cassandra Morgeson was almost certainly inspired by her. The scholar Jennifer Putzi, who wrote a thorough analysis of the marked bodies in The Morgesons,4 observes that Stoddard, who began writing The Morgesons in 1860, was a columnist for the San Francisco newspaper the Daily Alta California during the months in 1856 when the paper was covering Oatman’s return. Oatman was widely photographed and interviewed, and the Reverend Royal B. Stratton’s 1857 biography of her, Life Among the Indians (one of the last captivity tales before Native Americans were finally trounced, east to west, beyond the point of captive-taking) became a best-seller; it’s been in print almost continually since then.

In public lectures she delivered about her captivity, Oatman talked like a woman grateful to have been returned to white civilization, even though the details disclosed in her biography suggest she was fully integrated into Mojave culture, with a loving mother and sister (and, some speculated, a husband and children, which was unlikely). Fully aware, with nearly two centuries of captivity tales behind her, that Americans were hostile to white captives who bonded with their Indian families, she didn’t mention the upside of the Mojaves: that they were free-spirited, serial monogamists who saw sex as a marvelous pastime to be indulged and encouraged. She didn’t discuss—as had some female captives who resisted return before her—the freedoms Indian women enjoyed, beginning with (for the Mojaves) going topless and barefoot in the desert heat at a time when white women wore full skirts and petticoats. And she didn’t explain why, when the Whipple railroad survey party spent weeks trading and socializing with the Mojaves in 1853, she didn’t reveal herself as a white woman, though the Mojaves had told her she could leave at any time. Oatman’s tattoo pointed to both the life she was initially forced to live and the one she ultimately chose to embrace.

With her story of assault, kidnapping, tattooing, and Indian-adventure, Oatman was like a fictional character come to life. Her tattoo set her apart, as Hawthorne said of Hester, “taking her out of the ordinary relations with humanity, and inclosing her in a sphere by herself.” Although she married, adopted a child, and lived well as a banker’s wife in Texas, she could never be a pure Victorian lady with a facial tattoo perpetually recalling her life among “savages.”

Oatman, who was more than a victim and less than a heroine, is remarkable as a survivor and an adaptor in a nation of shifting boundaries and clashing cultures. As a symbolic figure, she’s been the object of fascination and speculation for a century and a half. Stoddard was just one of many artists to (allegedly) use her as a paradigm. Erastus Dow Palmer’s 1857 statue, “The White Captive” (in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art) was inspired by her, the California painter Charles Nahl painted the Oatman massacre in 1856, and a 1965 episode of Death Valley Days (starring Ronald Reagan) reprised her story. But she didn’t prompt further fictional explorations until the late twentieth century, when body modification became bookishly modish, especially for women.

*

Meanwhile, mainstream America gawked at tattoos as circus novelties in the late 1890s, disdained them as a desperate means to easy money through freak shows during the Depression, averted its eyes when they appeared on the arms of Auschwitz survivors in the ’40s, and reviled them as biker insignia in the ’50s and ’60s. As tattoos became indelibly associated with social deviance, they virtually disappeared from American literature for the first three-quarters of the twentieth century; one notable exception is Ray Bradbury’s 1951 collection, The Illustrated Man, whose title story introduces a carny with moving, premonitory tattoos that become points of entry for the other tales in the book.5

It was, oddly enough, crime writer Elmore Leonard who would return to Oatman and her tattoo in his 1982 Western story, “The Tonto Woman.” (Oatman’s face even appeared on the cover of his 1998 collection, The Tonto Woman and Other Stories.) Leonard, who had clearly done his historical homework, modified the details of her history by marrying her off before her kidnapping (in reality she was only thirteen when she was abducted), giving her twelve (not four) years with the Mojaves, and making her husband a cold, rich rancher who forces her, on return, to live alone in the desert instead of on his ranch with him. (By contrast, Oatman went to school and married a man she met postcaptivity).

But the main detail Leonard expands upon is her tattoo. His captive, Sarah Isham, asks the Mojaves to tattoo not just her chin, but also her cheeks: “I told them if you’re going to do it, do it all the way. Not like a blue dribble,” she recalls to Ruben Vega, a Mexican horse thief poised to steal her husband’s cattle. Impressed that she insisted on her own marks, he tells her to remember, “There is no one else in the world like you.” A fellow outlaw, he even touches the tattoos and says, “You’re in there, aren’t you? Behind these little bars. They don’t seem like much. Not enough to hold you.”

Fifteen years after Leonard’s story was published, Oatman’s tattoo resurfaced in Elizabeth Grayson’s So Wide the Sky (1997), a compelling prairie romance novel chock full of period (1860s) detail, marred only by jarring romance-novel euphemisms involving men maneuvering their “manhood” in the vicinity of women’s “mounds.” Grayson explains in the Author’s Note that the book was directly inspired by Oatman, whose photo she had seen in Time-Life’s Old West series. Cassie Morgan (could the author have been referencing Cassandra Morgeson?), a Kiowa captive for nine years, is returned to the cavalry with a facial tattoo and marries her childhood sweetheart, now a cold and bigoted captain turned off by her free spirit and strong will. By contrast, a hunky half-Indian scout named Hunter Jalbert groks her otherness and wins her heart. As in The Morgesons and “The Tonto Woman,” the love is consummated when the scar is touched: Jalbert caresses Cassie’s chin and says, “This makes you special… It makes you beautiful. It makes you mine.”

Cassie, Grayson writes, “had finally found someone who saw her for herself.”

In linking their characters with minority lovers, both Leonard and Grayson recognized the ethnic implications of Oatman’s tattoo. The white savage wore what amounted to Indian blackface, thus—it takes one to know one—only a dark-skinned man could really understand her. And though it’s possible that Jalbert’s comment, “it makes you mine,” is merely romantic gush, it does suggest that the tribal tattoo makes Cassie belong to him culturally.6

Every tattooed female character mentioned above bears a mark that carries sexual connotations or invites romantic interest. Hester Prynne’s A and Cassandra Morgeson’s scars derive from adultery; Sarah Isham’s and Cassie Morgan’s tattoos betoken a wildness that frightens their stilted white husbands and draws earthier, “native” men into their sexual spheres. The marks are the insignia of Puritans who’ve busted out, something Stoddard flags by defining the mighty Cassandra in contrast to her passive, enfeebled mother. “The Puritans have much to answer for in your mother,” her aunt observes sardonically. In recent years, however, the literary tattoo has shed its Puritan underpinnings once and for all.

In the ’90s, when skin art entered the middle class and middle-class women in particular became the fastest growing tattoo demographic in America, fictional tattoos started creeping into women’s fiction almost as quickly as they began peeking out of their hip-huggers. Kathy Acker inked her characters to mark them as outsiders, but the tattoos themselves were not individually symbolic, nor were they positioned as particular keys to their psyches. By contrast, in Emily Prager’s 1991 novel Eve’s Tattoo, the titular tattoo results from a midlife crisis exacerbated by white guilt. On her fortieth birthday, Prager’s white Christian protagonist, Eve, a snarky magazine columnist, gets the number of an Auschwitz prisoner tattooed on her arm. She earnestly compares it to an MIA bracelet and claims that as a forty-year-old without children, “I want to give someone life.” But the tattoo is also, says Eve, “about the hearts and souls of women. About me. I’m of German ancestry. I’m a Christian. I’m a woman and I have to know—do I have mass murder in my blood or what?”

Her friends are alternately appalled and embarrassed by her tattoo, which trivializes the Holocaust as it remedies Eve’s midlife meltdown. But it does succeed, as she had hoped, in making people confront history and jolts them, briefly, out of their complacency. “They suddenly looked not sophisticated or cynical, not fed up or bored, not played-out or wired, just human, exposed, their expressions softened with an empathy they would never have acknowledged that they could feel.”7 As in Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man, the tattoo hosts a cluster of narratives: each time a stranger asks about it, Eve concocts an elaborate new biography for her victim, whom she names “Eva.”

“Getting the tattoo was a radical act, she knew that,” Prager writes. “[A]nd it was bound to ignite some explosions.” The first occurs when her boyfriend, who turns out to be secretly Jewish, leaves her. She muddles on alone, identifying with her victim and fielding questions about her number, until she meets a genial Holocaust survivor who helps her realize that getting the tattoo was a woeful, even shameful, mistake. Soon after, in a strained plot twist, she’s in a car accident in which her arm is broken and requires surgery that expunges the tattoo.

Eve’s Auschwitz tattoo inverted a century of tattoo symbolism for women, and in doing so underscored the vast freedoms women had secured since Stoddard’s time. Rather than denoting a repressed woman coming into her own or a wild woman redeemed, it symbolizes a politically and sexually free woman trying to understand oppression. Unlike those of Cassandra Morgeson or the various fictional Olive Oatmans, her marking has no sexual significance—except in that it repels her lover. He not only refuses to touch it; he refuses to have sex with her because of it, then leaves her.

But the central freedom the tattoo underscores is Eve’s sexual, professional, and political autonomy. Like modern primitives who crave ceremony for their ritual-free lives and find it in mock tribal communities, Eve looks for purpose and meaning beyond her culture. “[I’m] a victim of unending privilege,” she tells the real survivor. “I have life to spare.” In a smart ironic twist, the novel concludes with her discovery that the victim she identifies with throughout the book was no victim at all.

*

Since the publication of Eve’s Tattoo, the literary tattoo has been imagined overwhelmingly by and for women. Why? Prager was writing at a time when women’s body issues began to saturate political discourse, from matters of choice, like abortion, cosmetic surgery, and surrogate motherhood, to forces beyond women’s control, like breast cancer and eating disorders.

The modern fictional tattoo explores both the age-old subject of cultural identity and a newfangled complex of contemporary social issues. The captive or punishment tattoo, traceable to Hawthorne and Oatman, is now being reimagined in the era of sex crimes and child abduction. Brooke Stevens’s over-the-top Tattoo Girl (2001) features a child kidnapped by a religious nut and forcibly covered (face excepted) with tattooed fish scales. The tattoos, however, have limited symbolism (the pastor-captor is a psychotic fisher of men), and they don’t evolve with or impact the story beyond labeling the victim as damaged goods. Similarly, in Joyce Carol Oates’s The Tattooed Girl (2003), an abused, white trash anti-Semite who’s been forcibly marred by murky, meaningless tattoos, washes up in a college town and enters a love/hate relationship with her Jewish employer. (She does, notably, wear a crude facial tattoo sometimes mistaken for a birthmark, sending us back, again, to Hawthorne.)8

More interesting, because the victim manages to turn her story around and becomes a tattooist herself, is Jill Ciment’s novel, The Tattoo Artist, published in August 2005. Set in the early twentieth century, it follows a Jewish painter of the ’30s, Sara Ehrenreich, who travels to a fictional Pacific island and is forcibly tattooed (on her face) by angry natives who blame her for bringing a deadly storm with her to the island. She stays on, ultimately befriending the islanders, learning to tattoo, and etching pictures of her receding past on every part of her body until she’s rescued thirty years later. Having lost her original identity both physically and geographically, Sara has only her elaborately inscribed body to call home.9 She’s a reverse Queequeg: a cultural castaway in a strange land, initially tattooed by a man named Ishmael. Ciment’s novel marks the transition from a plot peopled by tattooed characters to a story in which the act (and art) of tattooing is a dominant motif. By coincidence, it was published two months before the U.S. publication of Sarah Hall’s new novel The Electric Michelangelo, in which tattoo imagery, practices, history, and iconography come together, fully realized, in a lavish spectacle of literary imagination.

The Electric Michelangelo contains enough tattoo lore and wisdom to constitute a minor skin-art treatise. The title character is Cy Parks, a fatherless boy who apprentices with a seaside tattooist in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Morecambe, England. Cy’s mentor, Eliot Riley, is a troubled genius whose bad temper and epic drinking blunt the appeal of his intrinsic integrity. His name is significant: Tom Riley was a well-known British tattooist of the late nineteenth century. His American cousin, Samuel O’Reilly, was the inventor of the electric tattoo machine in 1891, a device that single-handedly delivered tattooing to the masses, and Riley was the first British artist to use it. Fittingly, the fictional Riley makes avowedly proletarian art: “It’s personal socialism, lad,” he says. “Everyone’s included, everyone gets to look in to a person and share them, like what they see or not…. Oh aye, and I’ll tell you this, lad: a tattoo says more of a fellow looking at it than it can do of the man who’s got it on his back.”10

In his shop, Riley is “bard-like, king-like, god-like, waging accurate and beautiful war over the bodies of those willing to allow his definition and rendition of beauty.” On the street, he’s a pathetic loser, despised for his lowbrow trade and demonic drinking. Still, he becomes a surrogate father to Cy. Riley teaches Cy not only tattoo art but art history, schooling him in Raphael’s “faked” genius, Rembrandt’s ugly beauty, and Blake’s visions of heaven and hell. Forced into adulthood first by his mother’s death, then by Riley’s drunken demise, Cy packs up, crosses the Atlantic, and opens his own shop at Coney Island. Like Riley, he taps into rich veins of human psychology. “There were instances,” he found, when his needle “unwittingly delved down into a soul and struck upon meaning, then confidential matter came up, unstemmable as arterial blood or gushing oil, and customers confessed the reason behind the art… the tales were revelatory and awful and enlightening… to tattoo was to understand that people in all their confusing mystery wanted only to claim their bodies as their own site, on which to build a beacon, or raise a rafter, or nail up a manifesto, warning, celebrating, telling of themselves.”

One such manifesto maker is Grace, an Eastern European circus performer with a large horse living in her apartment, who commissions Cy to outfit her with a full bodysuit of eyes. Instead of paying merely to look at her perform, she reasons, “they will pay to see me looking back at them. It will be a good joke. It will be like being the invisible woman… otherwise my body belongs to them.” Grace’s attempt to invert the male gaze begins as a gentle erotic act: much has been made historically of tattooing as a metaphor for sex—it is, after all, an earthy blend of submission, touching, penetration, and mixed fluids. But in Hall’s hands the process, sexually charged as it is for Cy (who is in love with Grace), is a matter of restraint and respect: though he fears arousal while working on her, he finds it possible to “put his hands on Grace professionally.”

In sixteen sessions over the course of weeks, the two discuss culture and politics, the war in Europe, and even the numbers being tattooed on Jews as they speak. When Cy asks her why she’s doing it if she doesn’t want to be looked at, noting that the tattoos themselves invite the looking, she’s livid. “I can’t say you can’t have my body, that’s already decided, it’s already obtained… All I can do is interfere with what they think is theirs… I can interrupt like a rude person in a conversation.”

But in a twist that, recounted here, would spoil the plot, the rude looks glancing off the figure of the Lady of Many Eyes as she revolves on Luna Park’s spinning podium provoke a ruinous reaction. A month later, when she’s gone from Cy’s life, their would-be romance aborted, he relives his “journey across her body,” and considers the possibility that “those were the times he was making love to her after all.” He also recognizes that to say he rewrote her body’s history (which both allowed her, for awhile, to make a huge amount of money and ended her career) is to say her blood is on his needles.

Hall has taken the fabric of tattoo history—Melville’s patchwork mapping motif (via Cy’s clients) and Hawthorne’s emblematic model (via Grace)—and quilted them together. Her story carries on a bit too long, pushing into the modern era, when a female piercer befriends Cy and the one-dimensionality of piercing—no graphics, no variety, no national heritage, no permanence—only offsets the semiotic richness of tattooing. But just as Bradbury’s tattoo opens windows onto people’s lives, Cy’s work unlocks an underworld of love and loathing, remorse and revenge, freakery and faith, confirming his discovery that “[u]nless brought to him howling and bloody and immediately from the canals of their mothers at birth, there was absolutely no such thing as a blank human canvas.”

So where does the literary tattoo go from here? Shelley Jackson has answered that question by chasing it off the page and onto what Melville called “living parchment.”

Until now, words described the literary tattoo; in “Skin,” they are the tattoo. Until now, readers received the story; in “Skin,” they are the story. “From this time on, participants will be known as ‘words,’” Jackson explains on her website. “They are not understood as carriers or agents of the texts they bear, but as its embodiments.”

Jackson’s project is a provocative reversal: while most tattoos are marks of individuality, hers acquire meaning only as a group, and lose their meaning in fragments when her story dies, word by word, with its carriers.11 And while some fictional tattoos in literature have had real-life counterparts—Olive Oatman and Sara Isham, Madame Chinchilla and Prager’s Eve—Jackson’s real-world tattoos, by pure coincidence, have fictional counterparts: In The Tattoo Artist, Ciment writes, “The islanders had designed themselves so that the sum of their creation was always greater than its parts. An individual’s tattoos were considered by the tribe to be no more meaningful than a word taken out of context.” The difference is, Jackson’s text will never cohere physically, considering her “words” hail from all over the world.

Still, Jackson’s communitarian gesture is touching: the body in this narrative is not, like Cassandra Morgeson’s, a battlefield: it’s a corpus expressing blind faith in literature—even if this is literature moonlighting as conceptual art (Jackson has degrees in both studio art and creative writing). One bearer signed on because she loves conceptual art and books. The project made her wonder “to what degree participants feel like the word defines them as individuals rather than simply signifying the story in which they participate.” She says she doesn’t know who her word (“you”) refers to, which she finds “very metaphysically amusing”; on the street, people see it on the back of her neck and assume it points to them. Jackson has gene-spliced the written word by giving it a secret life within her story and a public life as a stand-alone symbol contextualized by its wearer.

Another participant says her tattoo—“words,”—incarnates a lifelong relationship that has been paramount for her as a student and teacher of literature. Until now, she says, “I existed and interacted outside of the word itself. Now I am a word. Who is going to read, consume, and interpret me? Who is in my sentence? Am I part of an independent clause or a dependent clause? Is someone my adjective? Who verbs me? Would I like the other words in my sentence? Will I ever meet them?”

Though tattoos will surely continue to shape-shift on the printed page, there’s something satisfying about Melville’s ushering them into fiction through a character tattooed with “mysteries not even himself could read,” and Jackson, 150 years later, offloading them to readers she has physically implicated in a story that, for now, remains a mystery.