A membranophone belonging to the mirliton (or “eunuch flute”) family, the kazoo has a deep and profound history; and of the playing of many kazoos at once, we find a correlative history even deeper and more profound. In 1667, John Milton wrote of a massed kazoo chorus:

At length a universal hubbub wilde

Of stunning sounds and voices all confus’d

Born through the hollow dark assaults his eare

With loudest vehemence…

And Tumult and Confusion all imbroil’d,

And Discord with a thousand various mouths.

Some will argue, correctly, that Milton is in fact describing hell and its torments. But that’s only because the kazoo hadn’t been invented yet.

1882: Mysterious newspaper ads tout the Elkazoo, a miraculous new instrument: “The great Egyptian musical wonder. Original discovered among the ruins of the pyramids. … Astonishing it may seem, those can play on the Elkazoo that play on no other instrument.” Its New Hampshire manufacturer may be connected to prior ads hawking a “Vienna Eolian Labial Organ.”

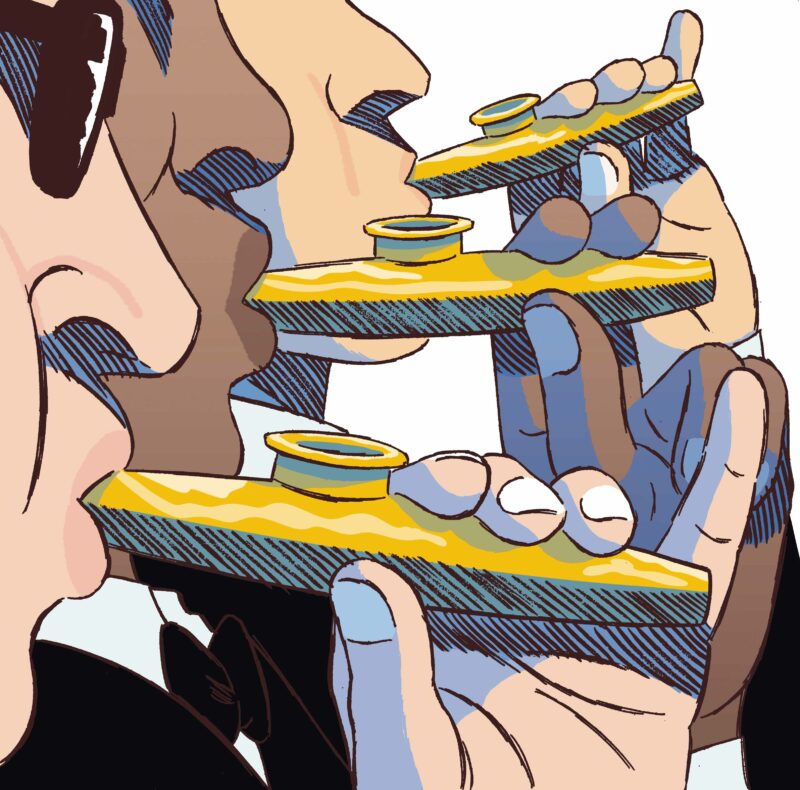

1883: Warren Herbert Frost receives US Patent 270,543 for a “Toy or Musical Instrument.” He claims that “this instrument, to which I propose to give the name ‘kazoo,’” can “produce imitations of birds and animals, as the caw of a crow, the crow of the cock, the moo of a cow, &c.” Wisely, he makes no further mention of music in the filing.

1884: Public events across the country are overrun by kazoo bands: a steamboat excursion in Boston, an electrical exhibition in Philadelphia, but above all, political rallies. Kazoo bands appear at election-night celebrations for Grover Cleveland in Indiana, Vermont, and South Carolina. “The inventor would be hanged, drawn, quartered and burnt,” reports a Washington, DC, newspaper, “but it is more than likely that he is kept out of the way in some insane asylum.”

1886: A Lafayette College student editorializes against the “barbarous dissonance” of a new campus ensemble: “The Kazoo band seems bent on doing their serenading when others want to study.”

1887: Kazoos are exported to London, where ads run for “The New Intense American Musical Instrument.”

1888: Election-year kazoo bands return like locusts. From the Democratic State Convention in Indiana comes a report of a forty-piece group “practicing regularly during the past two weeks, except as it has been interfered with by the police.”

1889: Kazoos are sold in India by Charles Gould & Co., which suggests buying four at a time, as “choruses using the Kazoo invariably receive repeated encores.”

1894: The popular American stage production Blue Jeans promises audiences both a “Kazoo Orchestra” and an “Intensely Thrilling Sawmill Scene,” though regrettably not at the same time.

1894: While a freshman at Yale, composer Charles Ives pens “A Son of the Gambolier,” which includes a “Kazoo Chorus.” He graduates with a D+ average.

1895: Warren Herbert Frost files to patent the Zobo, which is regarded as a somewhat improved kazoo, or perhaps simply a less unimproved one.

1896: Zobo bands form nationwide, including organized regiments of bicyclists, worryingly combining two current crazes. A young H. P. Lovecraft joins one band, later recalling: “I was a member of the Blackstone Military band… a star zobo soloist.” Its effect on Lovecraft’s development is not recorded.

1900: In an act of Brutus-like treachery, the Zobo Company secretary-treasurer, Louis Crakow, defects to create a Zobo knockoff: the Sonophone, or Song-O-Phone.

1901: Zobo ads target poor churches, assuring them that with enough Zobos, “A GRAND PIPE ORGAN EFFECT CAN BE OBTAINED” for “those with no pipe organ.” Similar ads for the Sonophone claim, not very convincingly, that this effect can be achieved with a quartet.

1902: George D. Smith patents a submarine-shaped metal kazoo, ushering in the modern instrument.

1907: A metal workshop that will become the Original Kazoo Company is founded in the Buffalo suburb of Eden, New York, producing kazoos based on the Smith model. For the next three decades, the kazoo, the Zobo, and the Sonophone battle for atonal supremacy.

1914: As wartime shipping lanes become uncertain, the Sonophone Company trumpets a new message to retailers: “THE SONOPHONE FILLS THE PLACE OF OTHER TOYS.”

1919: An ad in The Singapore Free Press reads: “With a Song-O-Phone you can throw a crowd into convulsions of laughter, astonish everybody, no matter how wise they are, frighten away burglars, secure sound sleep in spite of the snorer in the next room, win a victory in battle, win a girl’s heart, win a husband, square yourself coming home late, make a family happy, keep the young folks at home, pleasantly pass the long winter evenings on the farm, quickly put a child to sleep, be ‘IT’ at the sea-side or on the Mountains, cure everybody of the blues, and make everybody remember you with gratitude for life.”

1920: “Juvenile jazz bands”—marching bands of children dressed in military-style uniforms, playing in tight formation on kazoos and drums—form in mining towns in England and Wales. Like colliery brass bands, these are organized largely by miners.

1924: A “Kazoo Symphony” performs on KDKA radio in Pittsburgh, making kazoos inescapable even in the safety of one’s living room.

1928: The Ziegfeld Follies employs more than eighty Song-O-Phones in a stage production. In what is surely only a coincidence, one year later the world economy collapses.

1930: The US government, considering whether imported kazoos should be subject to a 40 percent tariff on instruments or a 70 percent tariff on toys, makes it official: “A kazoo is not a musical instrument.”

1930s: The Batistes, the famed musical family of New Orleans, form the Dirty Dozen Kazoo Band, initially to parade “all over town whenever boxer Joe Louis won a bout.” The kazoo becomes a fixture of Mardi Gras for the next fifty years.

1943: The Original Kazoo Company halts production for two years so that its sheet metal can be put to less destructive uses.

1949: Art Mooney and His Orchestra release “Doo De Doo on an Old Kazoo,” an experiment in kazoo maximalism. It is their first hit single to fail to reach the Top 20.

1951: The London trade paper Melody Maker claims the kazoo was invented by “Alabama Vest, an American Negro, circa 1840” and “built to his specifications by Thaddeus von Clegg, a German clockwinder of many attainments.” No source is given, and neither name appears in the records. In addition to their suspiciously Roald Dahl–like names, one might consider the name in the article’s byline: “Parp Green.”

1963: Thomas Pynchon’s novel V. features “an unemployed musicologist named Petard who had dedicated his life to finding the lost Vivaldi Kazoo Concerto.” The Crying of Lot 49 (1966) begins with the opus.

1971: The Pelaw Hussars appear in the British film Get Carter, in which uniformed children march with kazoos before a naked and shotgun-wielding Michael Caine. This remains the definitive cinematic appearance of a juvenile jazz band.

1972: Pierre Boulez refuses to conduct David Bedford’s new composition “With 100 Kazoos,” as it entails handing out kazoos to the audience. “He rejected my piece on the grounds that audiences would be stupid and would fool about with their kazoos in the other pieces too,” Bedford later explains.

1973: The band Kazoophony is formed by six musicians from the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. They perform such compositions as “The William to Hell Overture” at Avery Fisher Hall and Carnegie Hall in New York City, and at the truck terminal opening at the Emerson Street Dump in Rochester.

1978: The fledgling Rhino Records releases Some Kazoos by the Temple City Kazoo Orchestra. Purportedly recorded at the Temple City Moose Hall in California, the EP includes a cover of “Whole Lotta Love’’ that utterly destroys Led Zeppelin’s swaggering epic. It begins with just one kazoo, then two, then three, then four, and then Oh my god the vocal part. It is an atrocity and an act of genius; it is both the Hindenburg and the Mona Lisa of kazoo recordings.

1979: The Temple City Kazoo Orchestra performs on The Mike Douglas Show in an episode costarring David Brenner, Cheryl Tiegs, and Lou Ferrigno. They later play on Dinah Shore’s show, which they complain has lousy catering.

c. 1981: The Original Kazoo Company switches from buzzing animal-gut membranes to pink mylar. Defending the change, the company’s president notes that they previously also switched away from lead paint.

1983: Kazoophony cofounder Barbara Stewart publishes How to Kazoo, which sells more than one hundred thousand copies. Her book repeats the Melody Maker tale of Alabama Vest and Thaddeus von Clegg. References to both begin to creep into newspapers, books, and articles, and eventually into the Wikipedia entry for “kazoo.”

1985: A crowd of thirty-five thousand at the Virginia Tech–Vanderbilt halftime show provides kazoo accompaniment to the Oak Ridge Boys on their hit “Elvira.”

2000: Composer John Powell uses a kazoo orchestra on the soundtrack to Chicken Run and presents the result to DreamWorks executive Jeffrey Katzenberg. “The first time we tried it,” Powell noted in an interview, “he turned to me and said, ‘What the fuck are you doing?’ And then two weeks later he was asking us to put more kazoos in.”

2007: The Original Kazoo Company celebrates one hundred years of greater Buffalo–Niagara Falls metropolitan area dominance in kazoo production.

2013: Rhino Records cofounder Harold Bronson reveals in his memoir that the Temple City Kazoo Orchestra included himself, fellow Rhino founder Richard Foos, and “members of Stevie Wonder’s band.”

2019: Fans of local metal band Lamb of God descend with kazoos on Richmond, Virginia, to drown out a Westboro Baptist Church protest against a transgender legislator.

2023: A water-damaged and autographed Temple City Kazoo Orchestra EP turns up on eBay. It bears this inscription: “Andrew, invest in therapy.”