I.

In 1961, a thirty-nine-year-old housewife in a quiet Vancouver suburb began work on her third novel. June Skinner had come to serious fiction writing fairly late—reviews would later wonder how she found the time, what with all the vacuuming and cooking—and she kept it somewhat apart, typing up pages at night after her three children went to bed, or tweaking text after they headed to school.

Skinner’s previous two books, both written recently in this manner, and all under a pen name, had been dark and fantastical pieces. The first, O’Houlihan’s Jest: A Lament for the Irish, examined the author’s own Irish heritage through a mythic martyr figure. The second, Pippin’s Journal, was a Gothic turn set in a haunted nineteenth-century manor.

Her third work aimed closer to home. It starred two younger leads—their grand spats, if not quite their personalities, mimicked those of Skinner’s own adolescent daughters, Mary and Jan—who spend a summer in British Columbia’s Gulf Islands. Skinner herself had vacationed on one of these, named Salt Spring, and this was the model she had in mind as she detailed the novel’s own unnamed island.

For her daughters, the book—which was unusually dark for a work about young children—took shape in tantalizing fashion, appearing on the breakfast table a half chapter at a time. The novel was read at its writing pace, and this allowed its scenes and characters to grow in scale.

I am fairly sure I can picture what this was like for Mary and Jan Skinner—the way the book’s figures would have lifted off the pages with a strange insistence. What they could not have known then—and would not learn for another forty-seven years, when the Skinners’ story and mine finally came together—was that their mother’s third novel was actually going to have two futures. And in the second of these, the book wasn’t going to fade away at all, as it seemed to in the first. Instead, it would become the object of an unusual obsession, which would involve it being rolled out in much the same manner as it was for them, only repeatedly and to many hundreds of ten-year-olds about three thousand miles away, one of whom, in 1992, was me.

II.

Likely every primary school has its resident fearsome teacher, the one whose name rattles ominously through the hallways. Anecdotally at least, this seems especially true of small, old, Northeastern private schools, like the one I attended in Pennsylvania in the early 1990s. The outside world is slow to intrude on these places, and schoolmasters’ tics may be left to metastasize.

At our school, the whispered name had a particularly auspicious sound, because it was not actually a name at all. It was a word: Sir. Sir—his Christian designation, which even other teachers didn’t seem to use, was Derek Stephenson—was a centrally cast figure of intimidation, lifted from a Pink Floyd cafeteria or a Roald Dahl recess yard and dropped into our fifth grade (which, in keeping with the theme, was actually called B Form). The honorific was a British convention. Sir was American, but he had taught in the U.K., apparently at some grimmer analogue of our own school, a few decades prior. The schoolboys there referred to every instructor as “sir,” and the tradition had resonated with the erstwhile Mr. Stephenson, who’d imported the address on his return to the States. In England, however, he’d been a sir among sirs, in nomenclature as well as style. Here he was the only one, and the title had the opposite of its old generalizing effect.

This was helped greatly by the way he looked. As a physical presence, Sir was unignorable: tall, but more pertinently wide; a ropy comb-over; stern Harris Tweed jacket and baggy khakis; Hitler mustache; a scowl magnified by brown-rimmed spectacles; a bellow given extra timbre by Merit cigarettes. Teachers like this tend to come prefaced by stories from older students, but for the most part Sir did not, probably because they would have been superfluous. The moniker was like a coefficient in front of his general size and noise.

My own turn with Sir arrived in the fall of 1992, led by a crisp plot-twist. The academy had gone coed eighteen years before, but some classes still weren’t drawing enough girls, and ours lagged at a two-to-one ratio. The administration’s solution was containment: keep two homerooms gender-even, and make the third, Sir’s, all boys. It was an auspicious echo of Sir’s old English heritage, with its hints of carved paddles and ear-pulling.

If anything, the legend of Sir turned out to be extra true. Corporal punishment was long gone, but his classroom remained stuffed with antique rituals and codes. Sir seemed to employ some alternate version of a familiar language. Singulars and plurals were Anglophilically switched, his chalkboard schedule listing “Maths” and “Sport.” Even our own names were given a Sir patina. Next to our classroom door, there was a placard on which he had scripted the B-1 membership in an ancient font: E. Q. Bullock IV, J. D. W. Poe, T. W. Schell-Lambert. These looked like ancient var.’s of our own handles, as though we were people you’d only read about. More tellingly, he often just referred to us in the collective: “you twits.”

Sir’s syllabus was full of strange assignments whose value was never quite clear. He often asked us to draw various national maps in colored pencil (tracing was wildly forbidden). A typical weekend assignment: draw Spain. This did not necessarily coincide with any study of Spanish history. A task’s difficulty appeared to be its chief justification. Being good at things was important; being bad at them was a problem. Success always seemed to call on some odd brew of skills, ones that either weren’t teachable or, you’d think, weren’t worth teaching.

Sir seemed particularly keen on undertakings with the chance of great and public error. We were required to memorize poems, which we’d subsequently recite for the class. These verses all seemed to be by nineteenth-century Englishmen. We had little idea what they were writing about, and Sir didn’t offer guidance. We knew that Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” was freighted with our possible humiliation, regardless of our sense of “stately pleasure domes,” and this seemed to be the crux of the lesson.

The academic bled into the personal. When Sir returned papers or tests, he would distribute them facedown to the entire class, then bark our last names in seemingly random order—only when yours was shouted could you turn it over, or even touch it. You could never touch his desk. When you returned from the bathroom, he would grab your hands to make sure they were cold from washing. Once, when Robbie Harvey handed in a subpar essay, Sir tore it to pieces in front of everyone, and from then on “Harvey Confetti” was a term.

III.

In B Form, the sports period was held second to last every day. This meant that we sprinted around for thirty-nine minutes, then climbed back into our mandated shirts, ties, and blazers without the chance to shower. The class that followed would carry a surreal air, as though in changing into gym gear, we’d undone the orthodoxy of the dress code—a strong sensation, as jackets and ties were so mingled with our idea of being educated, especially being educated by Sir. That period had the feel of a postlude, beyond the text of the school day.

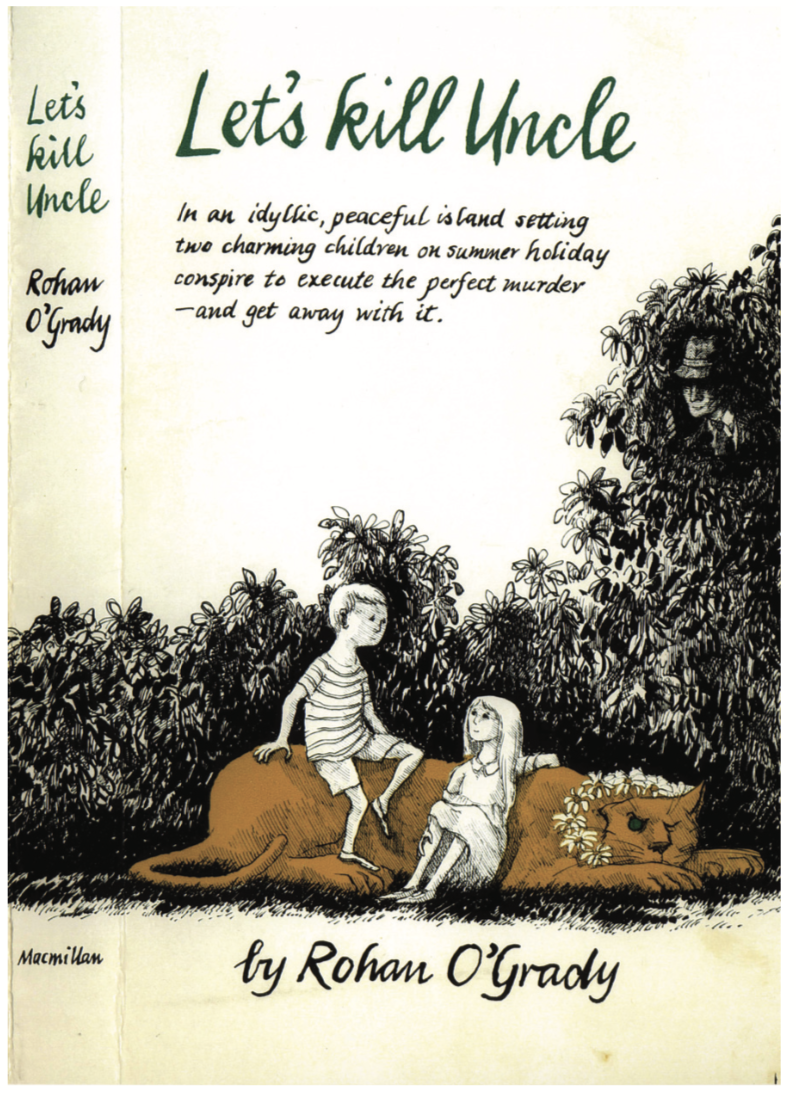

It was in one of these gauzy hours, when our guard was down and our minds were receptive, that Sir casually began to tell us about The Book. Like many Sir stories, this one took place in an earlier, more proper age. He described ducking into a used-book shop to kill some time. Possibly he needed to wait out a rainstorm. Browsing the old hardbacks, Sir happened upon an arresting title: Let’s Kill Uncle, written by someone named Rohan O’Grady, whom he had never heard of.1 The book had been published in London in the early 1960s. Curious, he’d bought the store’s only copy.

Sir went on to describe, in unusually fawning tones, how Let’s Kill Uncle had turned out to be not just intriguing but in fact outstanding—it quickly became our teacher’s “favorite” novel. The book was so good, in fact, that he’d commenced a policy of reading it aloud to each successive B Form class (by our turn, there had been a few decades’ worth). Yet he had never learned anything more about the book or its author. He now knew the text nearly by heart, but Let’s Kill Uncle remained as discrete and mysterious an object then as when he’d first stumbled upon it.

Thirteen years later, I would suddenly decide that these answers were very important to have, and I would begin the process of acquiring them. Sir would have passed away by this point; I would be twenty-three and living in a different city, not connected in any regular or obvious way to my old fifth-grade class. But that’s getting ahead of things.

IV.

Let’s Kill Uncle, by Rohan O’Grady,2 opens with two adolescents arguing over a messy incident: did Barnaby intentionally spill a bottle of ink on the captain’s charts, as Christie claims, or did he merely “bump it” with his elbow? The victim in question is the helmsman of the S.S. Haida Prince, a ferry toting passengers from Vancouver to the coastal islands. Barnaby and Christie, who have just met on board, will both be passing the summer months in one of these communities—one referred to, simply, as “the Island.” Christie has been sent by her mother to board with a Mrs. Neilsen (a.k.a. “the goat-lady”), while the orphaned Barnaby will be taking the holiday with his wealthy uncle. But for the moment, the pair is traveling unsupervised. And when kids travel unsupervised, apparently, they do things like feed chewing gum to border collies. “They just thought he’d like a wad of gum, the little bastards,” grumbles a vexed deck steward, who is left to inquire of the Prince’s first mate, “Do you know anything that will dissolve chewing gum? Something that won’t dissolve a dog?”

Almost as soon as we hear of Barnaby and Christie’s mischief, we spot its expiration. Waiting on the shore is Sergeant Albert Edward George Coulter, officer in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and customary greeter of the ferry. The Island’s lone surviving son of World War II, Sgt. Coulter is no whiny steward. “He stood as though guarding the Khyber Pass, his back as solid as his royal names and his brick-red neck immovable in his tight collar.” Learning of Barnaby’s pranks at sea, the stern Coulter sees trouble ahead: “The old people of the Island weren’t used to boys. Especially bad boys.” The novel’s first chapter ends with the Mountie’s resolution to give that boy a “firm hand. Yes, he’d watch that boy.”

For the ten-year-olds hearing all this, the teacher’s interest in the book was obvious. The novel opens onto a Sir-like world order: bad yet fixable children, brusque but noble authorities, a belief in paddlings as a cure-all. And there was glee in his voice as he took on these characters, the glee of having an argument backed up. Bastards was a categorical step up from bloody twits, and it missed none of us that this was aspersion by proxy. We were the bastards.

Still, just as in our daily schedule, knowing that was the case didn’t mean we knew why. If we spotted ourselves in these fictive characters, with their snotty voices and mussed hair, what we saw more keenly was Sir’s image of us. We never noticed ourselves doing things like throwing saltcellars or leaving blueberry pie on sofas, as Barnaby and Christie do on their Prince trip.3 But imaginary or not, that was the sort of behavior Sir’s class was designed to correct. There was even something familiar in its language—the talk of meting out “hidings” and “cheeking old birds,” the reference to an “Orient” we knew little of but which our poets often mentioned. The terms informed the style of naughtiness. Barnaby Gaunt wasn’t just any sort of delinquent; he was a twit like us.

V.

The young leads of Let’s Kill Uncle devolve even further once they make landfall. The early chapters of the book become a catalog of their offenses. Christie’s prissy urban ways don’t sit well with the goat-lady, who likes to prepare hearty country breakfasts—“fresh-picked wild blackberries, winking like garnets and half covered with clotted cream… pink ham curling prettily about the edges.”4 Christie sends back her plate “with a royal wave,” earning a rejoinder in Islandese: “No wonder you’ve got a complexion like a chicken’s foot.” Then there’s the child’s vanity and adult taste. At ten years old, she longs for a permanent.

Barnaby is rowdier still. Under the lax discipline of temporary caretakers the Brookses (his uncle remains darkly at large early on), the youth finds new outlets for his general program of mischief. If he’s not smashing the windows of Lady Syddyns’s greenhouse, he is decorating the Island’s prize bull, the Duke of Wellington, with “heliotrope-blue polka dots, the identical color of Mr. Duncan’s barn.” There is suspicion over the death of a pet bird named Fletcher.

It’s youthful misbehavior writ large. But an interesting effect emerges as the children reach the far extremes of naughtiness. In its opening section, the novel seems to cast a stern eye on its child leads; we think we are hearing a corrective from the grown-ups. But their crimes gradually become too vivid and plentiful for the critique to hold. In giving richness to their pranks, O’Grady gives her youths a sort of power: The book morphs from an apparent tract about behaving better to a tale of piquant delinquency.5 The children are running the narrative show.

A chief promise of much of children’s literature is evenhanded treatment—characters will get a fair shake, if not from each other then from the author. If they are being wronged, that will be made plain. But Rohan O’Grady is strangely reluctant to orient us this way. Her characters, at first, are demonic, and the only way we can read this is as allegory. As things progress, they’re empowered by simple abundance. Their badness fills the pages, and the mischief is drained. O’Grady’s harsh representations initially aren’t fair; then they aren’t really representative.

It is a critical development. At the most basic level, the early chapters of Let’s Kill Uncle, before the rule-breaking title is even broached, telegraph a certain dissolving of youth fiction’s laws. The lesson: Things have no obligation to work any particular way. The text doesn’t have limits. The author may be moody.

And hearing the novel as we did in the fall of 1992, walled off in its own time and space, the implications of this could be grand; the descriptions could bloom. Quickly—and with Sir’s rasp eliding differences between O’Grady’s characters and us—it ceased feeling much like any book we knew, in the sense that when you shut its covers the lines would obediently stay inside.

VI.

Ironically, this novel of fuzzy textual edges had sharp physical borders. Sir’s classroom was a place of tactility, of spaces that could either be transgressed or respected. There was his untouchable desk; our own desks were spaced perfectly, and he had mapped out who would sit where, with the effect that invisible property lines sprang up. When stray lacrosse balls smacked our windows, it seemed felonious. Things had an essential presence—they appeared in hard copy. And Let’s Kill Uncle was conceived as a sacred object. Remarkable measures were taken to ensure the book’s safety. Over our holiday break, which fell several chapters in, one of us, probably Kurz (Sir picked favorites for sport), was charged with taking the novel home and placing it under guard. And we were constantly being reminded that if we found any other copies, we should snap up every one and bring them to Sir, who would reimburse us. It was assumed that, at ten years old, we were all roughly on the case.

The book looked iconic even without Sir’s burnishing. Its hardcover was going soft, and the decades had produced a sublime discoloration—gray, brown, and yellow at once; like a literary hologram, it seemed to change colors with the light. The title was etched into the top of the spine in glinting gold leaf, the sharp serifs of the K spiking the verb with danger. (Let’s Kill Uncle’s salty-sweet allure goes past the incongruous three words, right down to the unsettling troika of initials. LKU: one is dull, one sinister, and one accommodating.) In a sense, the novel appeared as a sort of prime specimen of the fiction genus, fulfilling a matrix of color and feel and smell. Sir had happened upon it in a used-books shop; it was what one goes to used-books shops to happen upon.

Of course, being pitch-perfect as a novel also means hinting at difference from the rest—fulfilling the role means breaking it. And inside its ideally seasoned covers, Rohan O’Grady’s book increasingly plays with archetype. It is almost extra-novelistic; its urge to invent is irrepressible. Noticeable first in those preternaturally wild children—cutouts until they are uncommonly fleshy—the theme is revisited in her motley array of Island characters. These folks are constantly being tricked out with strange tics. One running subplot is Sgt. Coulter’s unrequited love for the wife of a neighboring clergyman, a Mrs. Gwynneth Rice-Hope, to whom he pens a weekly letter that belies his stern casting. “Mr. Duncan’s corn looks very pretty,” reads a typical epistle. “The leaves or whatever you call them are bright green and already have little gold tassels.” Often, O’Grady will include barbs her people don’t seem to deserve, as a matter of prerogative: Lady Syddyns, a “delightful old oddity,” is saddled with a fickle hearing aid and goofy hats. And when the author brings an aging cougar named One-ear into the proceedings, she breezily grants him a full interior monologue.

We’re in a sort of textual democracy on the Island. Plunked just offshore and never named, it has no government, and little narrative government. It is an anywhere a bit southwest of Vancouver, and anything can happen there. For one thing, literally anything seems able to grow. As Barnaby and Christie traipse about, they discover endless resources: “On the strange, fire-scarred mountainside they found ragged foxgloves rising bravely, and beneath cool ferns star-petaled trilliums winked at them. When they were thirsty they stumbled on secret icy springs. When they were hungry they found abandoned orchards where weary old trees were heavy with summer fruit.” Rohan O’Grady’s utopia of crops has nothing on her Eden of modifiers. The author is brashly anthropomorphic; her thickets can be tired, her flowers courageous. This is wild and verdant storytelling, fiction gleefully outdoing itself. Of course, by the same token, it is naturally tinted with danger. Nothing isn’t possible.

VII.

What I would not learn until much later was how much those passages, with their ecstatic and frankly rebellious opening of youth fiction’s doors, presaged a shuttering of them in the author’s own writing life. June Skinner, who was married to an American-born newspaperman with his own literary ambitions, and who in an inconvenient time of her life found a forceful muse and gave herself an elegant nom de plume—who, like her characters, executed a mad dash against type—ran up against the world soon after she completed her third novel.

Not long after Let’s Kill Uncle’s publication, June Skinner sold the script rights to William Castle, a producer of horror and gothic films. Several prominent actors were brought onto the project, including Mary Badham, the young girl who had just played Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird (not only a star, but a veteran of “kill” cinema), and the picture arrived in theaters in 1966. (The release was fairly wide, but it remained at least far enough under the radar that Sir never knew of it.)

For Skinner, however, the adaptation to film had become dispiriting. Many critical details of her novel were changed. The setting shifted from western Canada to the tropics, and the cougar that figured prominently in her plot became a tiger shark onscreen, a cat in name only. The unnamed island I would one day find in her pages was deemed “Serenity”—a stilted abbreviation of the atmosphere she’d conjured in text.

The movie experience suggests, of all things, disposability—in striking contrast to the gilded book that, not long after, the young Sir would first find and imagine as an object to protect. The film appeared, and the New York Times wrote, “Say this: It’s the least bad chiller ever made by William Castle,” and “certainly the best plot he has worked with in years,” and then it mostly disappeared. Skinner went back to work, but in her fourth novel, Bleak November, published in 1970, some of Let’s Kill Uncle’s élan is missing. It is a brisk horror piece (there is a characteristic sharpness in everything she writes), but also a bit of a hedge between the contemporary novel she wanted to write and the gothic she was asked to. What Let’s Kill Uncle offers is a sentence-by-sentence refusal to hedge on anything. It would be ten years before the author published her next novel, and that book would be her last.

VIII.

But we’re still at the part where anything could happen. Another fierce simile finally introduces the mythical Uncle, until now a spectral presence on par with Rohan O’Grady herself. The novel’s titular character arrives by air at the opening of the tenth chapter, his floatplane landing on the Island’s harbor after circling it “like a bird of prey.” By this stage, some insight into the title has been offered by Barnaby, who has been telling anyone within earshot that Uncle, a.k.a. Major Sylvester Murchison-Gaunt (Ret.), is no noble ex–army man, but a sadist who does “things—awful things.” And the awfullest is murder: Barnaby is convinced his uncle wishes him dead. At stake, apparently, is a 10-million-dollar inheritance, which would fall to the Major with his nephew gone. According to the youngster’s implausible yarn, Uncle has been chipping away steadily at the line of succession, taking out family members almost for amusement.

Barnaby is doubly flummoxed by all this. For starters, his closest relative is about to off him. More troubling still is that there’s little he can do about it. Even with unusual advantages—foresight into his impending murder, the ear of an acquaintance on the force—he is crippled by the trappings of being a kid. Sgt. Coulter dismisses his claims out of hand, trusting his sense of child/grown-up relations over what is in front of him. It is an identity problem, really. As Barnaby laments to Christie, he has been branded on the Island “a confirmed liar,” and attempts to talk his way out of it only add to the image. In Barnaby’s world, lying isn’t something you do so much as someone you are, and the supporting evidence comes mainly from your age.

Barnaby has run into the familiar wall of youth fiction and youth nonfiction alike—the part where things aren’t fair anymore. This was certainly a familiar state of affairs for the listeners of B Form, where seniority was the basic and unimpeachable rule. Sir, to a degree that caricatured teachers everywhere, was right because he was called Sir; rightness orbited him wherever he chose to stand.

Except in Let’s Kill Uncle, we’re headed somewhere quite different. O’Grady has us see that Barnaby is making a categorical mistake. Spending all his energies trying to sell the Islanders on his basic goodness, he has missed the big picture: Uncle doesn’t get to say what happens next. It is Christie who finally convinces him that new text is needed—that instead of dithering on edits they must take over authoring the story. Blasting him for getting hung up on being misunderstood—“Stop being such a baby, to begin with”—she produces a stunning crystal of a sentence: “We’ll just have to murder him first.”

IX.

What does it mean to outmurder someone? To murder someone back? Christie’s proposal is remarkable for what it suggests about youth fiction’s available options. This can be what happens next? And it speaks to what is compelling about her as a character. Whereas Barnaby always gets bogged down in the greater meaning of things, fretting about how his actions will be taken, she is a hard-line rationalist.

The distinction is more powerful than it seems. In Christie’s case, pure pragmatism becomes something of a narrative device in its own right. When she announces, after soberly assessing how she and Barnaby might handle things, that killing Uncle is the logical call, she is rather stunningly suggesting that murder can be just a medium. This amounts to a powerful point about storytelling. It makes authentic the notion that everything really is on the table. Murder can simply play as the opposite of shyness—a way to assert yourself.

Of course, for the book’s straight talk to be viable, it must also be applied to the project management. Killing Uncle, as Barnaby and Christie quickly figure out, is going to be really hard. “Victims could be run over,” they muse, going down a list of potential methods. “But alas, they could neither drive, nor did they possess a car.” Uncle’s strength as a swimmer precludes a drowning, the mode Christie “rather favor[s].” A gun seems to be the only option, and so the two set about finding one, an ongoing search casually described as “the old grind, the quest for firearms.”

Still, it’s a less-than-ideal solution, and O’Grady doesn’t hesitate to let us know how dire the children’s situation really is. “Had they any chance against a wily old pro like Uncle?” we are asked at one stage, as the Major remains several steps ahead in his own murder plot. And part of what distinguishes the novel is that we genuinely aren’t sure. When Rohan O’Grady lets the kids try to kill Uncle, she’s also informing us that it’s well within her purview to let them get killed. If few books about children allow murder from their protagonists, likely fewer still make those kids’ own demise so plausible.

The absence of the author—an unusually literal dilemma, in our case: there wasn’t even a dust-jacket picture—certainly added to this sensation for Sir’s listeners. It gave the book a startling degree of consequence and possibility. With no cushion in the real world, there was no sense of the writer as someone who would have to, at some point, obey laws. Faintly fictional herself (or, for all we knew, himself), Rohan O’Grady could offer a fiction that was entire.

What’s remarkable is the extent to which the real-life author of Let’s Kill Uncle had already moved in precisely the opposite direction by the time my class was introduced to the book. Rohan O’Grady as such ceased existing in 1970, after the publication of Bleak November. More than a decade later, in 1981, June Skinner published her final work, The May Spoon, under the pseudonym A. Carleon. The book is by far her most local and contemporary: presented as a collection of diary entries penned by a West Vancouver adolescent, it trades creaky Victorian houses for the Park Royal mall. It is also her most autobiographical—to a degree that is so slippery and transparent it becomes haunting.

The May Spoon’s central relationship takes place between two fiercely argumentative siblings, Isabel McMurry and her older sister, Marian. Isabel is our narrator—but she hates her name, so she opts to write under her grandmother’s maiden name, Ann Carleon. Ann Carleon was also the name of June Skinner’s great-grandmother. But does this make June Skinner, or even her mother, the narrator? Well, sort of. The book’s back cover features an unidentified old snapshot, taken in the late 1920s or early 1930s, of a young June and her real older sister, Eileen. The girls’ hair is bobbed, and they are wearing ruffled white dresses. But The May Spoon is set in the 1970s, half a century removed from Skinner’s own childhood. It is closer to her own daughters’. Read one way, Skinner seems to be writing as her great-grandmother, in her mother’s voice, about her relationship with her own sister, in her daughters’ world, with fight outtakes culled from her characters Barnaby and Christie, which were in turn based on Mary and Jan’s battles.

And things get heavier. Isabel/Ann writes, “The trouble with diaries is that they ought to be like stories… but nothing ever happens to me. On the other hand, if I lie (which I have an awful tendency to do) and put in interesting things that didn’t happen, then it isn’t a diary.” The dullness of her life is a reason to go fictional—or maybe the merits of truth are cause to bag fiction. She weighs pros and cons, and decides not to write a novel: “Dull as my life may be… I will tell the truth.”

The British avant-garde novelist B. S. Johnson wrote, “Telling stories is telling lies.” Reading Skinner’s final book, one senses that fiction itself, once a playing field of limitless options, has become oppressive. It is a novel that wants out of the game, that begs to be caught trespassing. Rohan O’Grady’s debut, O’Houlihan’s Jest, had eased away from the personal, cautiously building a myth as a way of speculating about family history. The May Spoon brings things full circle. Skinner does not so much quit writing fiction as dismantle its fictionality, abrading her last novel down to the street-level of her life.

X.

June Skinner’s final book is a trick of form. It looks just like a novel, but it is something else. And this is nearly a perfect reflection of what Sir was up to, or so it finally dawned on his students. Our classroom didn’t look like a novel, but that is essentially what it was.

As Let’s Kill Uncle changed, our impression of it as a teaching tool had to change as well. The novel eventually ferries between the baroque, top-down world we knew of our strict teacher, and contemporary notions of making one’s own way. In essence, it uses the vocabulary of the first to get to the second. For our purposes, that double allegiance was tough to suss out. This was another compelling aspect of the children’s decision to kill Uncle, where our grizzled reader was concerned: it is at once a completely vintage and totally modern thing to do.

And of course, it also contains a remarkably transferable image. A few tweens, tired of living under a cloak of fear, decide to strike back at their crafty oppressor. Yet if the symbol did carry over, what meta-meaning was there in Sir reading us a book about it? At one point in Rohan O’Grady’s work, Uncle puts Barnaby through a strange ritual, repeatedly offering and retracting a snack of milk and biscuits. The game sounds harmless, but it’s played as one of the boy’s harshest tortures—he runs screaming from the room—simply because Barnaby can’t figure it out. The boy’s biggest complaint about Uncle may be that he’s just so confusing. The same went for Sir. Acting like Uncle, while reading us a book in which our doppelgängers planned to murder Uncle, was itself quite Uncleish.

It is evident now, but took some unraveling to spot at the time, that this was the turn in a greater plotline. We naturally saw ourselves in Barnaby—and like Barnaby, we were inclined to mope about our rotten station. But it was Christie who held the solution to Sir’s life-size riddle. She is able to view her friend as a figment of someone else’s story. For Sir, the book was a mirror. Held up, it gave us a shot at seeing our surroundings for what they were: a fiction written by Derek Stephenson under a pen name, given the ring of biography by the use of our real handles. We were being goaded into declaring a certain kind of murder.

Absent weaponry, we were left with the metaphor of killing an Uncle: it was time to get on with something like the business of being our own authors. The particulars of this were hazy, but that wasn’t the point. In the book, Barnaby and Christie ultimately fail. They don’t even get very close. It takes a deus ex machina in the form of One-ear, a cougar who has reached his wits’ end, to pounce on Uncle and save Christie from his “well-worn” garrote. Sure enough, their survival pretty much comes down to a coin flip. But to O’Grady’s credit, the result, by this time, has been reduced nearly to a matter of passing interest. Carrying out murder is less interesting than deciding to commit it. The cataclysm has already happened.

Essentially, what Let’s Kill Uncle does is invent a before and an after. At a certain point, Barnaby and Christie realize they were children, a little while back. Sir deployed the book in a similar way—as a sort of calendar device. It ran a page break through his fifth-grade classes, so that by its conclusion the readers were on to something else. (If by its end they are not a bit impatient, they have missed the point.) And for a period of several decades, which he never knew was bisected by Ann Carleon’s bittersweet epilogue to fiction, he animated Rohan O’Grady’s set piece on self-determination, and told us without telling us that the next move was ours.

XI.

It’s often occurred to me that Sir might have wanted us to search for Rohan O’Grady forever, but never find her. The myth he fashioned around the author and her novel relied on both elements—the ongoing hunt and its perennial failure. But the problem with this way of looking for things is, sometimes you come across them. And this was how, in July of 2008, I found myself sitting in June Skinner’s living room in West Vancouver, British Columbia, sipping tea from a mug styled to resemble a cougar—painted in wildcat colors, with serrations on the handle suggesting teeth.

The two stories of Rohan O’Grady remained separate for a long time, and I’m not entirely sure why it suddenly felt urgent, in the spring of 2005, to find out about the one I didn’t know, and then bring it together with the one I did. But I think it had to do with a lingering lesson from the novel—something about getting to write the final chapter on my own. In a sense, the final untouchable Uncle that seemed to need killing was the old myth itself, the one dividing the novel from the real world.

Sir himself had died in 2002, suddenly and not long after retiring from teaching. I cannot get away from the notion that once the teaching ended, so, too, did Derek Stephenson’s great protagonist—himself. There were no more pages for him to appear on. But it was too late to get any better understanding of this from him. And for this reason, too, I turned to Rohan O’Grady.

To my surprise, after all the buildup, a few answers appeared right away. The book was apparently rare but indeed real—there were two or three copies floating around among used-book sellers—and with a certain sensation of magic I beckoned it to appear at my house. The longtime grail, a second volume of Let’s Kill Uncle, landed on my doorstep a few days later, looking improbably similar to the original I remembered: jacketless, with the dun hardcover and the wicked lettering.

Piecing together information about O’Grady herself was slower going. I gradually determined that she had written at least two books prior to Let’s Kill Uncle and one after, but I had trouble closing the system. Unhelpfully, Pippin’s Journal existed in three editions, each with a different title—the others are The Curse of the Montrolfes and The Master of Montrolfe Hall—and it took time for these several books to become one. That O’Grady seemed to have written a final book (The May Spoon), under a different name that still wasn’t her own, made for another hurdle. And what could it possibly mean that in March of 1991, about eighteen months before I entered Sir’s class, the English singer Morrissey had released an album called Kill Uncle? (Sample lyric: “Sing your life / Don’t leave it all unsaid / Somewhere in the wasteland of your head.”)

At a certain point in the process I finally lit upon the name June Skinner. This moniker appeared with some frequency in the frontispieces of the books, and when one of my online searches turned up a short bio of “Rohan O’Grady” in a British Columbian trade publication, unmasking her as Ms. Skinner and listing her as a resident of West Vancouver, I was fairly certain it was credible. However, for two years, my search remained stalled at that point. Even if Ms. O’Grady was Ms. Skinner, and Ms. Skinner did still live in West Vancouver, I couldn’t come up with a good way to locate her there.

During this time, I wondered if I had gotten as far as I would, and if that meant something—if I had been right to doubt the premise of the search and was in danger of ruining the subject I meant to clarify. That, of course, was Barnaby Gaunt thinking. Christie would have said I was just being a poor sleuth. And she would have been right. I had failed to notice a short aside in the bio—which was uncredited—mentioning that Skinner’s final book was released almost simultaneously with her son-in-law’s third. That novel was The Knife in My Hands, by Keith Maillard, who, I quickly discovered, had gone on to fill the years after Rohan O’Grady’s and Ann Carleon’s retirement with many volumes of fiction, and who was, if all my facts were correct, married to the former Mary Skinner, daughter of June. Maillard was also now the director of the University of British Columbia’s creative writing department, which augured many things, but most relevant to my immediate purposes, the odds that he had an email address. In the saga of Let’s Kill Uncle, connections can take decades to play out, or they can take half a morning. An hour later, I’d sent him an email glossing my strange relationship with a book his mother-in-law had written forty-seven years earlier, and an hour after that, I’d received an email with the following line visible in my browser window: “Dear Theo, My name is Mary Skinner Maillard and I am responding to your inquiry about my mother, June Skinner.”

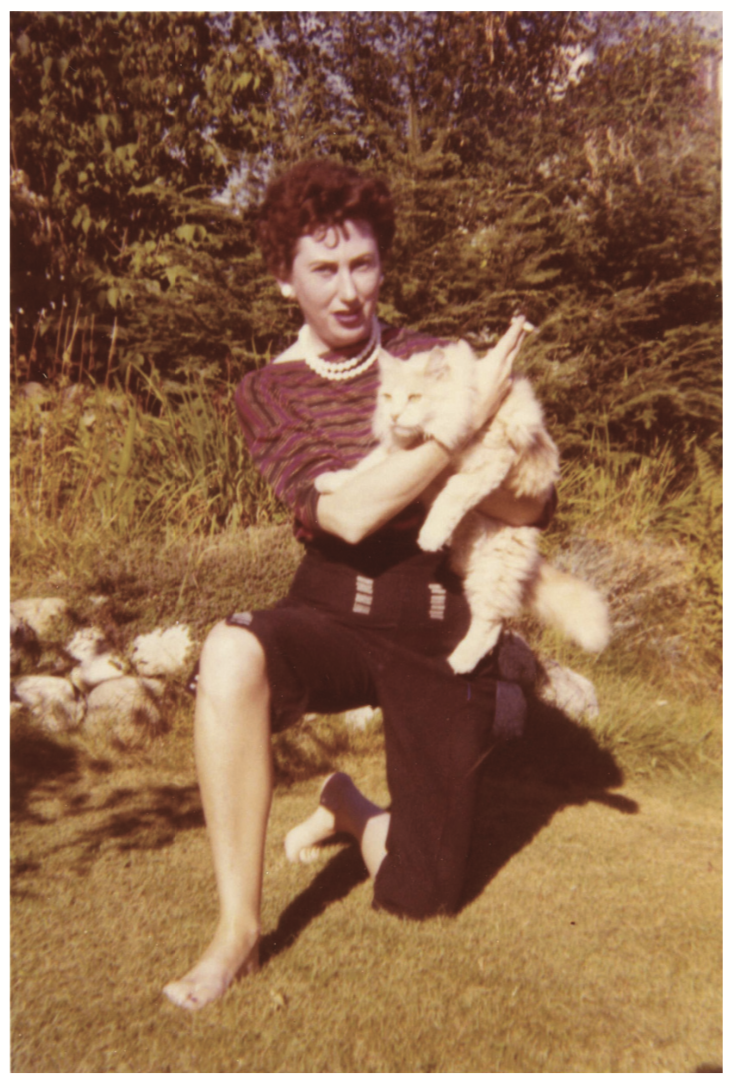

On the ride out to Ms. Skinner’s house from downtown Vancouver, my bus skirted the West End, old stomping grounds of the characters in Bleak November. After crossing the Lion’s Gate Bridge, I passed the Park Royal mall, site of many May Spoon afternoons. And inside her home, the now-eighty-six-year-old author and I, along with Keith and Mary, engaged in a surreal sort of sharing of notes. Mary brought out a scrapbook of review clippings from the early 1960s, along with a photograph, dated July 1, 1957, showing young Mary and Jan straddling a live cougar while June kept a firm hand on its back. Next to them stands a grouchy-looking zookeeper, a cigarette dangling from his lips. To my surprise, even One-ear had not been so fantastical. I passed around my old yearbook, with its photos of Sir, his glower still undimmed, and Mary immediately made the point that he reminded her of Uncle. It did not escape my attention that a remarkable inversion had taken place. Fifteen years before, I had spent many afternoons in Pennsylvania wondering about the impossibly distant Rohan O’Grady. Now I was in a different room in British Columbia, trying to reach back and invoke Sir for the author.

As I sat with June Skinner, looking out across the bay that, a few miles to the west, widened into the strait that washed up onto the Island’s twin, I could not escape the impression that she quite tangibly had gotten too close to her writing—that exactly what had made her third novel so magnetic (its totally fearless plotting, the depth of its deal with the reader) had worn on her. Her book had been sparked by that lack of quarantine, and the same thing brought her career to an early finish.

At the very end of Let’s Kill Uncle, as Christie departs with Barnaby on the ferry, her mood turns sour. Barnaby promises that she’ll still get her cut of his inheritance, despite their murder not technically coming off—typically, he can’t see that this isn’t what’s bugging her. Ever forward-thinking, she has moved on to a new plot: the eventual courtship of Sgt. Coulter. “I’m coming back when I’m eighteen and I’ve got a permanent, and I’m going to get him!” she vows. She takes out her camera and snaps a picture of the Islanders back on the dock, shouting, “Look, Sergeant Coulter, I got you!” The novel closes with the narrated remark “And she did, too.”

The line leaves things tantalizingly unclear. Does Christie really return and marry the Sergeant, or does her “I got you” simply refer to the photograph? The answer doesn’t exist in the book, but it does exist. At one point in our discussion, Mary Skinner turned to ask her mother if the implication had been serious. Had Christie indeed come back to make an honest man of the humorless Mountie? I hadn’t thought of asking this question myself; I didn’t know if I could glean plot points of Let’s Kill Uncle from beyond page 246. But the author answered without hesitation. “Oh yes,” Rohan O’Grady said, as though she’d been thinking about the couple just the week before, and she grinned.