Mayakovsky was better known as a person, as an action, as an event.1

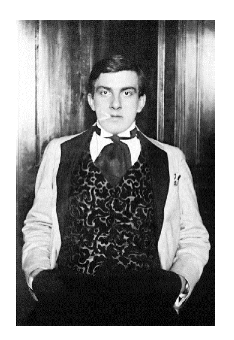

Even at this distance—more than seventy-five years after his death and nearly twenty years after the collapse of the government he fervently promoted—it remains difficult to account for the phenomenal nature, the sheer outlandishness, of Vladimir Mayakovsky. As unofficial poet laureate of the Russian Revolution—“my revolution,” he called it—Mayakovsky had unrivaled authority and glamour, taking on multiple responsibilities and roles—orator, playwright, magazine editor, stage and film actor, poster maker, jingle writer—with a singular mix of self-mockery and martyrdom.

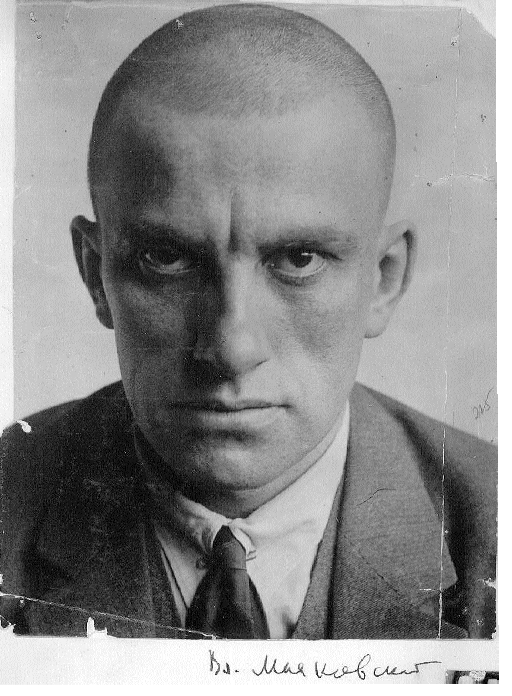

Photographs of the poet—particularly the glowering, shaved-head portraits taken by Aleksandr Rodchenko in 1924, when Mayakovsky was thirty-one—display a kind of proto-punk ferocity, a still-burning aura of tough-guy tenderness, soulful defiance. The poems are virtually inseparable from this persona, as Mayakovsky made theatrical appearances in his verse and made a spectacle of his personal life. “He felt the need,” his friend Viktor Shklovsky wrote, “to transform life.” And so it followed that for Mayakovsky, poetry itself was transformative. He channeled experiences directly into his work while being convinced that the resulting poems could pace and project the ideals of a new social order.

*

He was calm, massive, and he stood with his feet slightly apart, in good quality shoes that had metal reinforcements and tips.

It may be bewildering, now, to imagine a poet expecting his words to translate into an active force for change, but this conviction was at the center of Mayakovsky’s life and work, and it was shared by a generation of artists coming of age in the revolution’s early, ecstatic wake. (Auden’s famous circumspect assertion that “poetry makes nothing happen” would have been greeted by Mayakovsky with a howl of derision. Rodchenko and his typographical counterpart, El Lissitzky, would have whipped up terrific corroborating posters.)

Mayakovsky was born in Bagdadi, Georgia, in southern Russia, on July 7, 1893. His father, a forest ranger, died from blood poisoning when Vladimir was twelve, and the remaining family—Mayakovsky’s mother and two older sisters—moved to Moscow, where Vladimir went to high school. He had an early start in anti-czarist sentiment: incited by a pamphlet brought home by his sister, he participated in a pro-Bolshevik demonstration the year before his father’s death, became an active party member at age fourteen, and was arrested twice before being jailed for aiding the escape of a political prisoner from Novinsky Prison. He was locked up for seven months, and served much of the sentence in solitary confinement. His first arrest, the previous year, followed from his involvement with an underground printing press—solidifying the link in Mayakovsky’s mind, you might guess, between printed matter and high-stakes consequences, between language and action. In jail, at any rate, he began to write poems.

*

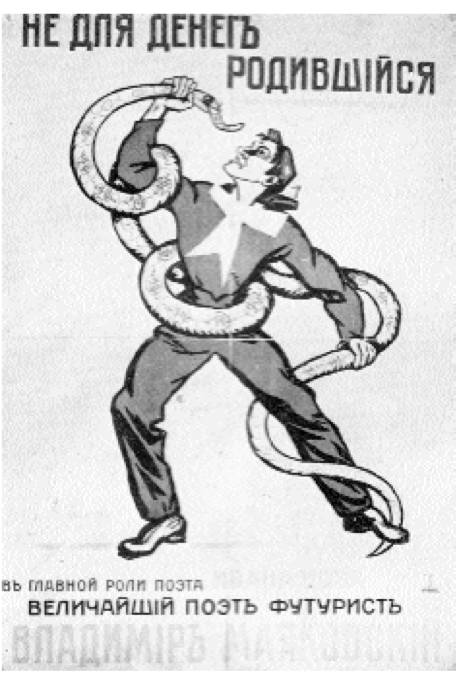

Once released, Mayakovsky enrolled in art school in Moscow, nurturing a strong if conventional skill as a draftsman, but his gift with words took precedence when his older friend, fellow student and provocateur David Burliuk, heard Mayakovsky recite a poem during an evening stroll. Burliuk declared Mayakovsky a genius. This opinion, which Mayakovsky promptly adopted, carried the poet through a quick apprenticeship and led to the formulation, with Burliuk and other young accomplices, of a Russian division of Futurism, a willfully scandalous bohemian/literary project. Like their Italian predecessors, Russian Futurists were enraptured by city life, by machine-age energy and speed, and they matched a hunger for new forms with a well-publicized contempt for artistic tradition, for contrived sentiment, for bourgeois complacency and decorum. In the words of Bruce Chatwin, the Futurists “saw themselves as a wrecking party which would unhinge the future from the past.”2 Despite, or, as likely, because of the movement’s anarchic clowning, its embrace of the inexplicable and the absurd, Mayakovsky came to absorb and enact a central Futurist ambition: to bring art closer to life.

*

For a long time, Mayakovsky had been buffeted and tossed around. He knew how to use his elbows.

Futurism’s self-promotional spirit was manifested in Mayakovsky’s glaring yellow-orange blouse, worn proudly during a traveling cabaret, a virtual two-year reading tour that began in St. Petersburg in 1913 and swept through broad patches of Russia. Accompanied by Burliuk and a handful of fellow Futurists, Mayakovsky became a supremely commanding performer, having conjured within himself a remarkable arsenal of poems, and having perfected a confident style for reciting them, in a booming voice, at once laconic and fearsome:

He stands upright, hands in his pockets… His cap pushed to the back of his head, cigarette moving in his mouth. He smokes nonstop. He sways on his hips, examining the public with cold flashing eyes.

“Quiet, my kittens.” He keeps people under control.3

The 1912 Futurist manifesto, “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste,” may now seem tamer than its title suggests, but the slap of Mayakovsky’s early poems can still carry a sting. They collide irony and sincerity, lyricism and violence, and they are uniquely pitched in a mode that James Schuyler later described as “the intimate yell.” Notable among these early outbursts are two sensationally sustained longer pieces: an eighteen-page verse play written when the poet was twenty, Vladimir Mayakovsky, A Tragedy (goofily derived from Hamlet), and then, two years later, the breathtaking A Cloud in Pants,4 an unclassifiable, delirious declaration of anguish, an apocalyptic love song. In both works the central protagonist shares the poet’s name and is essentially the same towering, raw-nerved character who, in the course of an eventful career, converses equably with the Eiffel Tower, Pushkin, the sun, the Brooklyn Bridge, and (in what became Mayakovsky’s suicide note) “the ages, history, all creation.”

The Mayakovsky persona was intact from the start, a voice at once seductive and hectoring, casual and elevated—a versatile voice employing the language of the streets, encompassing the immediacy and messiness of an engaged life. Mayakovsky was working outward from a love of words and an implicit political commitment that evolved alongside current events. By 1914 his anarchic/Futurist fury converged with a heightened recognition of the horrors of the First World War. And when at last the Bolshevik Revolution broke out, in 1917, the shift from smart-ass cultural iconoclasm to a seething political conscience to a revolutionary demand for the overthrow of the entire social order—this evolution came to seem inevitable, requiring merely a few brave forward steps. Mayakovsky took these steps, redefining Futurism to accommodate the emerging Soviet state, what Theodore Dreiser, among many contemporaries, regarded as “the most tremendous government experiment ever conducted.”5 While the experiment remained open, Mayakovsky addressed and was welcomed by a vast proletarian audience. It was a time of wrenching change, wild chances, blinding hope.

*

The lady of the house, with her large face and beautiful eyes, hunching her slender shoulders, looked at Mayakovsky as if he were a not quite tamed lightning.

Mayakovsky liked company and crowds, but by definition he was a poet, an individual spending a great deal of time alone with language. He understood loneliness as an index of conscious existence, and he recognized poetry as a way to break through loneliness.

Central to this effort, and to Mayakovsky’s enduring personal mythology, was the poet’s off-kilter romance with Lili Brik, who remained married to Mayakovsky’s publisher, patron, and friend, Osip Brik, for the entirety of their relationship. (Mayakovsky met the couple in 1915 and shared living quarters with them for most of his adult life.)

The Mayakovsky-Brik alliance can be considered emblematic of a generation’s impulse to break with convention, but it would be hard to name another sustained literary ménage so brazenly lived out in public and confided in print. Lili Brik’s efficacy as icon and muse can be traced through Mayakovsky’s career, but it is most conspicuous in About This (1923), dedicated “for Her and Me” and first published alongside eight tumultuous photo collages by Rodchenko. Rodchenko’s cover famously displays Lili’s detached and staring sphinxlike head, and half of the other illustrations show her looming over smaller figures and landscapes. What did this woman have to do with the forging of a new national consciousness, the future of socialism, the common good? The question is caught in the center of this poem, and indeed the center of Mayakovsky’s life, like a kite whirling in a high wind.

About This was, among other things, a willed respite from the poet’s ongoing effort to establish a coercive, public, “revolutionary” voice. He’d spent nearly three years (1919 through 1922) illustrating and supplying slogans for thousands of propaganda posters for the Russian Telegraph Agency. Working with Rodchenko in 1923, he devised jingles and entire ad campaigns for state-manufactured goods. (“There have never been, nor are there now, better pacifiers. They are ready for sucking until you reach old age.”) Following Lenin’s death, in 1924, Mayakovsky produced his longest poem, Vladimir Ilich Lenin, a monumental funeral procession, a bronzed tract celebrating Lenin as myth and messiah. The poem, full of topical references and foreshortened political theory, was a nominal hit, read perennially before huge congregations of workers. Very Good! (Khorosho!), commemorating the revolution’s tenth anniversary, in 1927, nearly matches Lenin in length and stridency. Throughout these didactic epics, Mayakovsky reliably smuggled in an element of cartoon exaggeration, a measure of mock heroism rising through the solemnity, but the poet’s radically personal lyricism was checked at the door. In his autobiography he described abandoning a novel during this period, admitting disgust with his own imagination, a preference for “names and facts.” John Berger’s assertion that poetry was a system of exchange for Mayakovsky, that the poet and his work depended on a circuit of immediate and measurable interactions, finds a sharp confirmation in a seldom-anthologized piece, “My Best Poem” (also 1927). In it, Mayakovsky portrays himself at a reading, responding to “questions / and barbed requests,” when a newspaper editor rushes to the podium, interrupting the poet with a whispered announcement, which Mayakovsky translates to his audience in a thundering voice:

“Comrades,

the workers and troops of

Canton

have occupied

Shanghai!”

Elated and humbled, Mayakovsky takes in the answering ovation, fifteen minutes long—“as if / they were mangling tin / in their palms.” It’s what he really craved: poetry as uproarious breaking news.

But hindsight grants a blood-soaked historical view of the revolution’s final costs, and Mayakovsky’s bluntest propaganda now feels hollow, unconvincing, and coarse. (At least, that’s how it registers in the English translations I’ve encountered. Agitprop doesn’t travel particularly well.)

*

Love was set as a distant goal, and the road leading to that goal was the same as the great goal itself.

Mayakovsky was always writing about the future. Resurrection and immortality were constant twin motifs. (Suicide was the other side of the coin.) In the last stretch of About This, the poet exhorts a scientist in the far future to restore him to life:

Your thirtieth century

will abolish

the trifles that tore our

hearts.

Will return

what we

had not time

to love properly

of future nights

countless

stars.

Revive me,

if for nothing else,

because I,

a poet,

cast off the heap

of everyday

trash,

to wait for you.

But as the consequences of the revolution became increasingly clear and dire, Mayakovsky found it impossible to wait for a diminishing future, and he chose to escape into a darkness always swimming near the surface of his poems. On the morning of April 14, 1930, at age thirty-six, he took his life with a self-administered bullet to the heart.

It was a death foretold in the poems, but its impact was convulsive. Few chronicles of Soviet history fail to mention Mayakovsky’s suicide as a turning point, on the heels of Trotsky’s banishment to Central Asia and Stalin’s Five Year Plan (the forced collectivization of Soviet agriculture, resulting in famine and an estimated 10 million deaths between 1928 and 1931). Even so, by 1935, Mayakovsky’s posthumous reputation was in the shadows, and Lili Brik enlisted a new lover who had government connections to help engineer an improbable proclamation, issued by Stalin: “Mayakovsky was and remains the best and most talented poet of our Soviet Epoch.” The opinion carried an ominous addendum: “Indifference to his memory and to his work is a crime.”

And so Mayakovsky’s second death, as Boris Pasternak defined it, went into effect. To this day, a good many citizens of the former empire, force-fed Mayakovsky in school, can count themselves guilty of this crime. For all his originality and intransigence, and even as he grew increasingly embattled and embittered, facing repressive government policy and vicious personal attacks, Mayakovsky had become a Soviet mascot and shill. The final burden of his self-reproach was, clearly, staggering.

But he staggered valiantly, up to the last. In his only poem completed the year of his death—commonly titled, in English, “At the Top of My Voice,” but presented in Ron Padgett’s impudent translation as “Screaming My Head Off”—the poet again addressed readers of the future, ideally workers redeemed at last by the triumph of communism, readers for whom a crazed Mayakovsky could reassert his unrepentant individuality, his status as a tough case, a “blabbermouth,” an untamable beast:

I’ve had every kind

of bullshit

up to here!…

For you

who can afford

to be healthy

I’ve had to sing

with the big blue tongue

of death.

To you I must look

like some flying

prehistoric lizard.

Well, yes and no. For this reader, Mayakovsky remains extraordinarily human. His best poetry has stayed fascinating and urgent. Jean-Luc Godard granted him a posthumous cameo in Les Carabiniers (1963), and you can trace Mayakovsky’s direct influence in the work of Frank O’Hara, Allen Ginsberg, and Kenneth Koch. The tender and titanic voice echoes into the current century, and in this way—a way even Auden would approve—Mayakovsky continues to make things happen.

1. All italicized quotes are from Viktor Shklovsky, Mayakovsky and His Circle, 1940; English edition translated and edited by Lily Feiler, New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company, 1972.

2. “George Costakis: The Story of an Art Collector in the Soviet Union,” in Bruce Chatwin, What Am I Doing Here? New York: Viking Penguin, 1989.

3. Sergei Spassky, in Mayakovsky and His Fellow Travelers, Leningrad, 1940, in Wiktor Worozylski, The Life of Mayakovsky, trans. Boleshaw Taborsty, New York: Orion Press, 1970.

4. Mayakovsky’s most famous poem, Oblako v. Shtanakh, is best known in English as A Cloud in Trousers; Matvei Yankelevich’s tough-minded new translation takes in the fact that the original Russian does not feature this internal rhyme, and shtanakh signifies clothing of an untailored everydayness, making pants more fitting than trousers.

5. Theodore Dreiser, Dreiser Looks at Russia, New York: Horace Liverwright, 1928.

This essay excerpted from Night Wraps the Sky: Writings by and about Mayakovsky edited by Michael Almereyda, published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, LLC. Copyright 2008 by Michael Almereyda. All rights reserved.