I. “SO FAR AS I KNOW, IT’S THE FIRST BOOK BY A WHITE WRITER ABOUT A BLACK FAMILY IN THE SOUTH.”

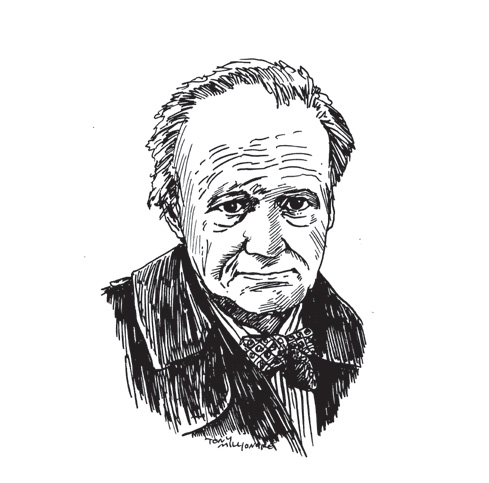

MICHAEL ONDAATJE: John, you began as a writer of radio plays. When did you start?

JOHN EHLE: Well, I was born in 1925, so it would be… hell, I don’t know, I used to be very good with numbers, but then I got older and older. When I went to Chapel Hill, I worked for a radio station, and I registered in the Department of Radio and Television, and the first assignment was to write a radio play and bring it in on Monday. So I did. I found it pretty easy, and the students liked my little play, and I liked theirs, and suddenly we were “radio playwrights.” When I graduated, in ’49, I left the university, and the faculty members wanted me to come back. They got me on salary, actually. And they got a grant from a national foundation for me to write radio plays for a series called American Adventure.

MO: One of the things that’s wonderful in your novels is the dialogue, so I’m wondering if you recognized that talent in yourself when you were writing plays.

JE: Well, the personality of a character in a story comes through in what he says. And in radio, there’s not much else.

MO: This is how long before you began to write fiction?

JE: One of the advisors for the series was Paul Green, who was a playwright, and he said, “Now, John, are you going to keep writing just plays?” And I said, “Paul, I did write a short story, and it got rejected everywhere.” Except one person had written “Sorry” on the bottom of it, and I didn’t know whether they meant the story was sorry or they were sorry they weren’t going to publish it. It was a story about a black family. And Paul Green said, “Well, let me see it.” And when he read it he said, “Now write the next two chapters and an outline of the remainder.” And I did, and he said, “That’s fine, now write the book.” So it’s about a Negro family in Chapel Hill, which I called Leafwood, I think. And we sent it to Scribner. And they wrote one of those famous letters that anyone who wants to write about black people would get. “I know you’re surprised by this, but Scribner has decided not to publish this book.” So the next time Paul Green called, he said, “John, would you mind if I show your book to Frances Phillips? She’s a relative, and she’s the head editor of William Morrow and Company.” And the next thing I got was a telegram, the next day, from Frances Phillips, accepting the book.

LINDA SPALDING: And what was that book?

JE: Move Over, Mountain. It has just been reissued. So far as I know, it’s the first book by a white writer about a black family in the South. Morrow had some trouble getting it into the bookstores. They said, “We don’t have any black readers, buyers —what are we going to do with it?”

MO: When you began writing fiction, were there influences? Who were the writers you read around that time?

JE: Oh, Eugene O’Neill was the writer I was reading. I found a pattern in his work. He contrasted life—the affairs of life, living well—and love. If a person chose love, then his life was going to pay for it. If he chose life, his love life was going to pay for it.

MO: Were there fiction writers you were reading then?

JE: No. I took courses in nineteenth-century drama, twentieth- century drama. I don’t remember ever taking a course in literature. In the summertime, I would take off for New York City and live in Greenwich Village. It was very easy back then to find an apartment for two or three months in the summer while the owners went off to the Hamptons. I rented apartments in seven different places in Greenwich Village. I was married somewhere along in there….

MO: What was this second novel?

JE: That was called Kingstree Island. I’d married Gail Oliver, and I would get up early in the morning and write twenty pages. I didn’t know how to write the damn thing, and I didn’t outline it, you see. I was living on Washington Place. Well, damn it, I wrote twenty pages a day about this island and these people and it no more made a book than a catbird, but eventually it was published by Frances Phillips, and it was well received, although I wasn’t very happy with it.

LEON ROOKE: Twenty pages every day, minimum, on a gallopading iron Underwood. Entire neighborhoods shook. Street repairs were necessary when John was writing a book.

JE: The Underwood was yours, I think. Mine was a Remington. Then I decided maybe I should write about the mountain people—the first white people who had come up with the intention of living here. I wrote 150 pages and I couldn’t figure out where the damn book was going, and again I didn’t follow— I never have followed—my friend’s advice. I didn’t outline it. So I shelved it and started another book, which came to be called Lion on the Hearth, and I finished it and sent it out to my agent, and out of the sheer meanness of agents, he did not send it to Frances Phillips at Morrow. He sent it to Buzz Wyeth at Harper. And so there you go, that’s just the way that agents do things. I had written two nonfiction books, meanwhile. The first one Frances published. And that was the story of a minister in New York City and his work with Puerto Rican immigrants. If, indeed, a Puerto Rican coming to America is an immigrant. They have the right to come. But the next book I wrote was an as-told-to book about an SS man in Germany who ended up in Vietnam and Bangkok after escaping from the French Foreign Legion.

MO: The novel, Lion on the Hearth, where does it fall historically?

JE: That would be 1920, or somewhere in there. It’s a mountain story. Then I got down the 150 pages of the other book, The Land Breakers, and I went ahead and finished it and sold it to Harper & Row in 1964.

MO: So by now you’ve written two books about the mountains. You’ve written Lion on the Hearth and The Land Breakers, which deals with the first settlers, and by the end of that book we do not want to let go of those families. The Plover girls in the books that follow continue to taunt the men innocently, utter free spirits. At that time, did you imagine writing a whole series of books?

JE: Yes, I did. I didn’t have any sort of talent. I did know that I would be very hard-pressed to name the characters in a subsequent book, because a movie contract I’d signed required rights to the characters. I did not know until I was having a movie done later for another book that there were ways around that.

II. “IT WAS REALLY ONE OF THE MORE PRODUCTIVE PERIODS OF MY LIFE.”

LR: John, maybe you should give them a précis of the good work you did in the governor’s office in the ’60s.

JE: Well, Governor Sanford was looking for someone to develop new projects with him. I didn’t know him very well, but I went to work for him, and I was there for eighteen months, and while I was there I was doing research for the next book about the building of the railroad using black labor after the Civil War. I was able to call the state library and ask them if they wouldn’t mind putting together a little research for a state project.

LS: We won’t print that.

MO: Sure we will.

JE: There were actually eight or nine projects we developed. It was really one of the more productive periods of my life. The North Carolina Film Office was the first project, the Governor’s School was the second, the North Carolina School of the Arts. And then various antipoverty programs, including what became the North Carolina Fund, which was the first statewide and nation supported project to try to find out how we could solve the problem of poverty.

LR: All John’s ideas and all his projects were actually coming to fruition with considerable results, like the black/white/first-ever Southern, residential Advancement School, which he has neglected to mention, or his astonishing notion, through his friendship with Anne Forsyth, of the R. J. Reynolds family, and her foundation, of supporting untold numbers of primary-school black kids in the whole of the South through untold years at fancy East Coast schools such as Exeter.

LS: What worked and what didn’t work?

JE: I don’t know. I mean, I never participated in the administration of any of these programs. We had actors touring the schools, doing scenes from Shakespeare—some of the people who later worked with Rosemary.

LS: So you and Rosemary are together at this point?

JE: No. I got word that the fellow who lived in my house with my first wife and me, right there at the campus—and, goddamn, I gave her that house in the divorce—anyway, we had two rooms we rented out, and one of them was to John Dunne, a Morehead Scholar, who saw himself as knowing how the South should be run better than the Southerners did. He had organized with one black man and another white man, and they had planned demonstrations in Chapel Hill to try to get the city to do a program admitting black people to restaurants, for instance, and schools, and so forth. And the boys then made the mistake of blocking traffic on a football afternoon, when the rich alumni come into town in their Cadillacs.

LR: You’re talking fifty or sixty thousand people. And your civil rights book, The Free Men, came out of it.

JE: There they were, blocking the main goddamn crossroads of Chapel Hill! Franklin and Columbia streets, sitting down and refusing to leave, and having to be picked up and bodily carried to the paddy wagons. Boys and girls. Nothing in the Chapel Hill paper about it, except the Daily Tar Heel, which was the student newspaper. John Dunne was sent to prison and so was Quinton Baker, the black partner, and so were some others. And over one hundred people were arrested. And every single one of them was given a prison sentence which was held in abeyance, to be exercised should they demonstrate again. All illegal. And the university was absolutely quiet about it, so I went over to the prison, used my governor’s office calling card. I now knew the head of the prison department very well. John was quiet, in despair. I told him I’d write a magazine article about the whole thing if he’d tell me what he was doing and, so help me god, I ended up writing a book about it. Which Harper didn’t want to print.

The book kind of made Chapel Hill look bad, and made the liberals look bad. Buzz Wyeth invited me up to his house, and he explained to me they wouldn’t be able to publish it, and how he liked my mountain books. And I told him I wanted him to think about that, because maybe I’d have to go find another publisher. And I remember he followed me out to the car and shouted, “We’ll publish it, John!” Meanwhile I was in New York City working for the Ford Foundation. I got a lot of money for civil rights, and actually for the Protestant Church. But I must say, it was not helpful with getting another novel written. And by the time I wrote it and got it to Harper, it was some years after The Land Breakers, and that was a great mistake.

MO: I’m very interested in how you researched your novels, because the reality of those times is just remarkable in them: how to build a certain kind of cabin, how to make certain foods, how to sew a dress, or make shoes….

JE: I was reading books. And I made index cards. There’d be one section on horses, and one section on bears, and one section on gardening or cooking or whatever.

LR: John often takes the “hands-on” approach to research. He’s tried growing French vines in these mountains, he’s canned peaches, cured country hams, worked the pottery wheel. Once, he and I built an outhouse, for the sheer experience of doing so.

MO: So when you said you were able to use the governor’s office for research, what kinds of things were you able to get from them?

JE: Oh, construction of the railroad. For The Road. They were able to supply me with the actual hearings held by the General Assembly of North Carolina into the tactics being used in building this railroad that resulted in so many deaths. I also had something written by a friend who said there were four hundred blacks killed from explosions and cave-ins. They built seven tunnels by hand with horse or mule. A lot of people died of pneumonia, too, because they were out there working in the wintertime.

LS: That was when they first used chain gangs, mostly black prisoners, right? And there is the amazing caboose brought up, where the prostitutes live, also locked in. The books are political, but in totally unexpected ways. Later you wrote a book about the Cherokee. When did you write that nonfiction book, Trail of Tears, about their removal?

JE: Well, that was after I’d written the other mountain books. I got a call from an editor at Scribner—I’m finding it awful hard now to remember what the hell I’m talking about—and he asked me if I’d do a book on the Cherokee removal. I said, “Marshall, I don’t have any information about this thing. And I don’t really want to get into it.” And he said, “John, you’re going to do it, I’ve already told the sales force and they are very excited….” So, hell, I had a storehouse of stuff written by scholars all over. None of it written by Indians. Cherokee also has an outdoor drama—a pageant—filled with feathers and other things. And it’s just not quite right, to be honest with you. But it’s very successful and plays to a thousand people a night, or some goddamn thing.

III. A MAN CHOOSES LIFE OR LOVE.

JE: My parents didn’t like any of my books. I visited home without mentioning them.

LS: But did you ask them questions about family things?

JE: No. But my uncle Ed had told me that in the old days of his childhood, he had an uncle who traveled out west, and occasionally came home, and when he came home, his father literally had to strap the boys to the bedpost to prevent them from going off with that uncle when he left. So I started Lion on the Hearth with that story in mind.

My uncle Ed was a fine fellow, a big success of a man, and he had these wonderful leather bags, and everybody made way for him. You could take the streetcar to the other station up to Asheville, or you could walk. “We walk,” my uncle would say. “I’ve always liked the wide road.” He had these two bags, and he’s walking—he’s walking down the middle of the road. So I remembered things like that.

LS: Why did your parents object to your books?

JE: Probably because they didn’t have enough Jesus; they didn’t tell you how to be saved!

LS: Well, I think they do tell you how to be saved. But I’m wondering if some of that was… For example, there were little tidbits, you were saying the other day that your grandmother did not invite her daughters to her weekly lunches, only her sons. And I believe there was someone like that in The Winter People. Maybe the family was finding bits of themselves that they didn’t think were particularly flattering.

JE: I got a letter from my father reflecting my mother’s opinion, and I wrote him back a letter. I sent both letters down to Chapel Hill to the Southern Historical Collection, where my papers are, including letters from my grandfather, who was the one who was a reader. He had the largest private library in Morgantown, West Virginia, which is a university town. And he used to send me books to read—Uncle Wiggily, Sabatini, and some Dickens. I think I had the first Tarzan book.

MO: Someone like Faulkner—was he a role model in any way for you? Like him, you pick that postage stamp of soil to write about. But, unlike Faulkner, there is a chronological line of this land’s history.

JE: No. I’ve not read much Faulkner. I probably read Thomas Wolfe more—I remember Look Homeward, Angel. Aunt Netty knew the source of every character in it and what date they were born. But my mother read it and told me it was a dirty book. So there you go.

MO: What did you like about Wolfe’s work?

JE: I liked his use of language, among other things. And his sense of humor. There was nothing I disliked about him. I think he’s a very fine writer.

LR: In Chapel Hill, at the university, Thomas Wolfe was the great hero. He was the legendary literary figure prior to Paul Green. So I wonder when you started doing your plays; maybe that was a legitimate outgrowth of the Thomas Wolfe—let’s call it “industry”—at Chapel Hill.

JE: No. Well, I don’t know if it was. I hadn’t read him then. But you’re right, he was a legend, and should have been.

MO: Is Wolfe the main North Carolina writer before your generation, Leon?

LR: As I see it. John might have a different opinion.

JE: I think I’d go along with that.

MO: Did the characters in The Land Breakers, like Lacey Pollard, for instance—who in the first half of the book seems one-dimensional, but who then returns to the mountain with a sense of the world outside, “the wide road,” and has seen everything that’s going on out there, as opposed to this small valley—did you even imagine Lacey Pollard emerging that way, or was that something that evolved as you were writing? Because he becomes a wonderfully tragic character.

JE: It goes back in a way to Eugene O’Neill. A man chooses life or love. Love meaning he would have stayed with his wife, and life meaning he would have gone to find out what the world was like. So he evolved. He didn’t evolve as much as he should have. I mean, he didn’t have a chance. I’m not sure that killing him with the bear was the best idea I’ve ever had, but it was convenient at the time.

MO: Wasn’t it Lacey Pollard who says to Mooney, “There’s no proper way to start a country”? He has a sense of the world, as in a way August King learns to have in The Journey of August King.

JE: And Mooney Wright comes back in August King.

LS: In Michael’s favorite scene. I looked across the room when he was reading it, and he was weeping.

MO: Well, that boy, that boy’s moment, when he touches August King’s face as recognition of something. It’s just… But now, who is that boy? He’s about sixteen years old at the end of the book.

JE: It would be the grandson of Mooney.

MO: You’ve essentially got two families: you’ve got the Wright family and you’ve got the King family, who appear all through these stories.

LS: You’ve got the Plovers, too—those wild, natural creatures unlike any others.

JE: But normally my books are written about people who are in the social upper strata, which makes them different from most Appalachian books. I didn’t know that’s what I was doing, but in looking back on it I would say I was writing about people who were part of the structure of the society they were in. They were leaders in it.

LR: I recall one statement of yours from your classroom, when I was a student in that classroom. You were saying something on the order of this: that fiction, like drama, at its simplest but most essential level, is about characters wanting something and setting out to achieve it. Do you recall this approach?

JE: Oh yes, that’s certainly the Hollywood approach. You want to achieve something, maybe a woman, or a man (if you’re a woman), or you want to steal some money, or it might be anything. But normally, in Hollywood, it had to be something the audience wanted them to be able to get. Or escape, sometimes you wanted someone to escape something.

MO: But this thing about the society is interesting. Because at first glance you don’t really think it’s about that. Being land breakers or first settlers, everyone seems close to the earth. That is all they appear to be obsessed with. There isn’t a sense of an organized community.

JE: That’s right, and so whatever community there is, those people become the leaders.

LS: It’s a very North American vision in that, here, the people who founded places, even though they were riffraff when they left their original homes, became the leaders.

JE: That’s right. You take these people who came up the mountains—Mooney Wright and Imy… They had never in their lives, and even their parents’ lives and their grandparents’ lives and on back through time, been allowed to own land.

MO: So part of the drama is how these people take on responsibility for a community.

JE: But it wasn’t in my mind that they were doing that. I wanted to write about people who were smarter than I am. I found, in my teaching days, that students were always writing about people who were not as smart as they were. That was a mistake being made by virtually every student in a classroom.

LR: It’s still true—

MO: —of a lot of famous writers.

LS: One of the most interesting things I found about The Land Breakers is that moment where Imy had died and along comes Mina. And Mooney really desires her. He really desires her. But on the other hand, he checks out Lorry, and that’s where his founding-father status emerges, because he figures, “She’s got two sons, that’s an advantage. They can give me a head start. This woman knows how to milk a cow properly, how to weave or whatever.” It’s fascinating to me. It’s calculating, but it’s not cold. It’s a warm and loving marriage, but it’s determined by Mooney’s decision to have the right woman and not the one he desires. I just find that so interesting. Everything would have been different if he’d gone off with Mina.

JE: No, no, no. Mina didn’t know how to sweep a house.

LS: And that moment when Lorry throws the first wife’s broom out—Imy’s broom—and makes her own. You know, and it’s better made. Wonderful stuff. I think what I started to say was that your sense of the person who wants to walk the wide road—to me all the women have that, more than the men. They seem worldly and wise in a way that the men don’t, quite. The men have to find it, but the women seem imbued with self-awareness. And fortitude. Even the Plovers.

IV. “WELL, YOU CAN DO IT WITHOUT ANY TROUBLE IF YOU’RE SITTING IN YOUR WIFE’S DRESSING ROOM….”

MO: What’s interesting to me about August King, though, is here’s a man who thinks he’s doing wrong all the way through the book, who’s fighting the founding-father voice or official moral stance. But, of course, August is right in what he does. You say the story evolves as you write. Was there a sense, when you were starting that book, of how it would end for August?

JE: No! No! We were in Hollywood. Rosemary and I had married the year before. She had just borne a baby, Jennifer. And we had a nanny for the baby. And we had a car, we rented a car, and we lived in Beverly Hills in a rental house, nice big house. Had the mistake of renting a house with white rugs—a Beverly Hills idea, I guess. And so Jack Lemmon was with her in a play, and he lived in Beverly Hills, and probably others from the play lived in Beverly Hills. But nobody offered to take Rosemary back and forth, of course. I think it’s a Hollywood thing that you had your own car. I had to drive her, in other words, to her performances and to her rehearsals. It’s forty-five bloody minutes to get there and forty-five minutes to get back to where the baby was. And forty-five to go back and get her, and forty-five minutes to get home. And how many stoplights would that be? So one day I decided I would just not go back. Jennifer and the nanny were getting along, and I didn’t much like the nanny, anyway. I brought a pad with me, so when she went out to do whatever it was she was doing onstage, I started writing. I liked the first page or two, and I like it yet. “A creek is an artery of a mountain, though its blood is not salty.” I think that’s the first line.

LR: One great quality of all the books is they are brimful with just riches of detail. For instance—a lame example, perhaps—in The Journey of August King, when the man is packing for his trip, he packs fifty pounds of coffee, which at the time struck me as a lot of coffee. Maybe it wasn’t, but I mention that merely as an example of those details that bring such vigor and life to the manuscript in combination with the richness of the language. It’s magnificent. But how did you come up with all those details?

JE: Well, you can do it without any trouble if you’re sitting in your wife’s dressing room and don’t have anything else to do.

MO: OK, so you started writing August King in Rosemary’s dressing room….

JE: I started writing about the place, maybe two pages about the place, and then I had to find a character, and it turned out to be August King, and something had to happen. And he saw a runaway girl and talked to her, and she didn’t talk very much….

LS: No, but the conversations between those two are the best dialogues ever written.

JE: And they weren’t in the movie at all. The director cut all that. He decided that August King just did not like the idea of girls or boys being slaves. But, you see, August was part of his community. He was a leader. And to get involved in a thing like a runaway slave was a very bad idea for his own sense of citizenship. But at the same time, when he got involved, he became rather proud of his success.

MO: And the loss of everything in the procession—his geese, his cow… It’s something that at first glance you don’t realize until you read more of your work—that animal life is equal to human life in these stories. That the cow or the goose is as important as a child. They are much more than property. It’s important to remember this when we come to The Journey of August King, even though it’s never mentioned, for he loses everything on his moral journey in helping a slave girl escape. All those animals… it’s like taking parts of his whole life away from him. An animal is what you raise and nurse and what you really own.

LS: I know Michael always says that it’s hard to say goodbye to your characters when you finish a book. So maybe you thought, Well I don’t really have to say good-bye if I resurrect Mooney in another story.

JE: No, I was always very glad to get rid of a book. I didn’t worry about what the next book was going to be. You kind of put it in its little casket and nail it up.

MO: John, I think there is more human character and more animal character in these books than in any contemporary novel I have read. It’s not just the Plovers or the Wrights or the Kings or the settlers and hunters and lost husbands who eventually return, but the red sow, and the milk cow, and various dangerous or benign bears—all of them are magical…. And then there is also this sly wit of yours hovering around in the books. I just wish these books were more available. What a shame that they are still just a delicious secret. They should be reading you in schools. Everyone should be reading you for the pleasure and adventure and history in these books.