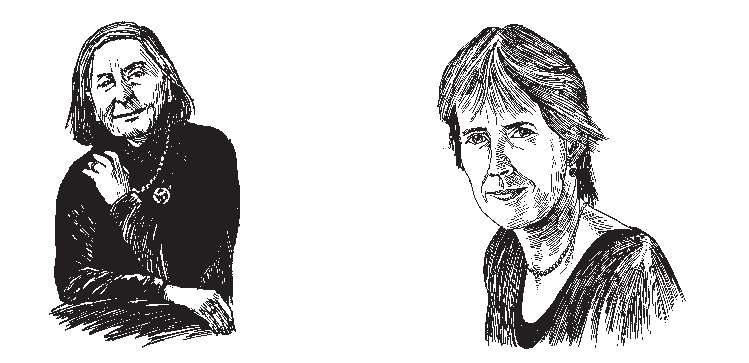

Joanna Scott is the author of two collections of stories and eight novels, most recently Follow Me (Little, Brown, 2009). She has lived with her family in Italy, pursuing her fiction, but is settled in upstate New York, where she teaches at the University of Rochester. Joanna is a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, a Lannan Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and the Rosenthal Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Maureen Howard is the author of nine novels and a memoir, Facts of Life, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award. The Rags of Time (Viking, 2009) is the last in a series of novels celebrating the four seasons. She is the recipient of the Academy Award in Literature from the Academy of Arts and Letters. She was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and made her way to New York where she has lived for many years with the comfort of family. She teaches at Columbia University’s School of the Arts.

Scott and Howard met when they were seated next to each other at dinner at a Houston writing festival one night in 1991, and continued talking at a PEN/Faulkner gathering in Washington, D.C., later that year. Joanna was expecting her first child. Maureen and Joanna have been talking children and writing ever since. Their girls are now well grown. The exchange that follows took place over email in the winter of 2009–2010.

JOANNA SCOTT: Maureen, I’ve been thinking about your memoir Facts of Life and its relationship to the fictional remembering that goes on in your new Rags of Time. I wonder if I’m right to sense that the two books share an energizing tension? On the one hand, a home is a writer’s necessary refuge—the work gets done behind a closed door. On the other hand, a home can be a “stifling refuge” (a phrase you use in Facts of Life), and the world outside the door, with its layered history, is always beckoning. The first thing your fictional writer does in The Rags of Time is to head out, away from home, into Central Park.

MAUREEN HOWARD: The exploration of place: I say that as though to introduce a classroom spin. Today we will concern ourselves with Flannery O’Connor’s confinement to Millidgeville, Georgia where she discovered the saved and the damned; to Naipaul’s childhood in Trinidad which became sacred to him in England. Well, if I seem unable to swing free of Bridgeport, even now recalling the chug-chug of factories in WWII, it may be to reconsider the best of times. In Natural History, both...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in