Robert Smigel blew off dental school and moved to Chicago, the home of the Second City Theatre, because he loved sketch comedy and wanted to make it his job. Within two years he was the lead writer of a theater revue (All You Can Eat and the Temple of Dooom) that was a hit and got him hired at Saturday Night Live.

When I met him I was a student of sketch in Chicago and writing my own craziness with numerous groups. Robert liked my notions, we hit it off, I moved into the theater crash-pad he shared with other fringy actor types, and we started planning a show we would write together. He was hired at SNL before we got too far. Two years later I joined the staff there and got my ass kicked around the block. Robert, however, did fantastically well, writing many of the most memorable sketches of the Downey Jr. through Carvey through Sandler years: The “Cliffhanger” sketch that ended the ’85-’86 season, William Shatner’s “Get a life!” nerd-fest sketch, “The McLaughlin Group,” “Cluckin’ Chicken,” “Da Bears Fans,” and “Schmitt’s Gay Beer.” Beyond the legendary sketches, there are countless super-funny unheralded pieces that would make a boxed set of best-ofs. I was there when he wrote many of these and it was intimidating to observe.

The best sketches are great concepts, funny on their own, that also provide the opportunity for hilarious performances. Robert combined these two qualities in every sketch, and he did it very well. He worked hard, had an amazing ability to concentrate, even after a night of no sleep. He simply had skills far beyond those of the other newcomers who arrived at the show when I did and equal to those of many seasoned veterans. How the fuck did he do that? I would wonder to myself as he wrote one perfect piece after another.

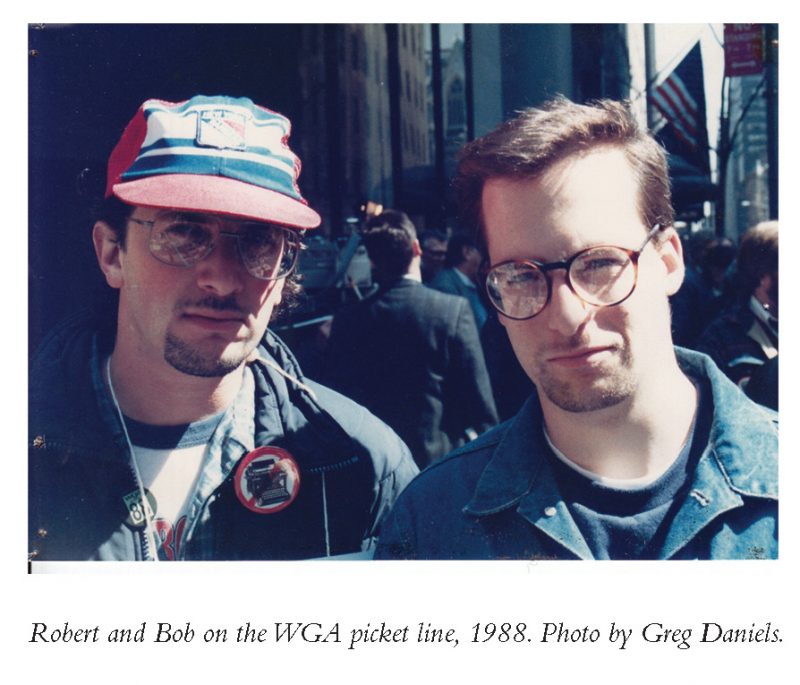

I was in the Believer’s offices in San Francisco a year ago and they asked me if there was anyone I’d like to interview. I immediately thought of Robert. Though he’s better known now for his cartoons and his work as the first head writer of Late Night with Conan O’Brien (where he created Triumph, the Insult Comic Dog), I wanted to focus on sketch writing. We agreed we’d get to it at the first opportunity. Many months later, Robert was doing a panel at San Diego Comic-Con to promote the DVD of TV Funhouse, his animations from SNL, so I took the train to San Diego and we rode back to L.A. that evening in the backseat of a Town Car with a tape recorder. Luckily, there were traffic problems, so we had almost enough time to explore “the question.”

—Bob Odenkirk

I. THE CORE JOKE

BOB ODENKIRK: Where did you learn to write sketches? Because I feel like I had such a massive learning curve. It was so hard for me. I think I wrote funny sketches when I was in junior high, really funny sketches that were kind of like clear-eyed, but that was just luck, I didn’t know what I was doing.

ROBERT SMIGEL: Really?

BO: Yeah, but they weren’t simple, they weren’t one joke things. They were just kind of good story sketches, and funny and silly. But I didn’t know what I was doing, especially when I went to SNL. Then I watched you and you seemed to have certainty about how to build a good sketch.

RS: I had it in All You Can Eat too. I mean, that’s why I got hired. Because in that comedy group I wrote a lot of the material. Some of them were like Second City sketches, but some of them were TV sketches that were on stage. You know, I was more of a TV kid. You read more books and you had a more balanced life in terms of absorbing entertainment. And I was obsessed with Saturday Night Live. It was a Rupert Pupkin affect. You know, he was not bad in The King of Comedy – I mean, Rupert Pupkin, himself. When he actually got the opportunity he was good. It was not an exciting kind of good but he was completely competent. And it’s sick – you’re just so obsessive that you absorb. He was turning himself into a completely different person, and adopting a completely honed TV personality.

Don’t get me wrong, I like to think, and I like that you think, that I have innate talent that makes what I write “the exciting kind of good” more often than not. But I definitely absorbed the template from watching. I was obsessed with Saturday Night Live when it was bad, with Jean Doumanian. That year I watched it, I was just fascinated by the craft and I wanted to see if it would ever get good. I was probably emboldened, on some level, to see it be bad. And you know the reason I moved to Chicago is I ran into Tim Kazurinsky. He was a new cast member. They’d all gotten fired and they brought in Tim. They only did three shows and they were already a lot better. I ran into Tim that summer, and he was so shocked I recognized him. That’s how big a fan I was. He was on it for three shows, and he’s amazed, “Jesus, nobody recognizes me”, so he stopped and talked and he told me about The Player’s Workshop of the Second City, an improvschool in Chicago. So I tried it because I met him, and that’s the only reason I went.

BO: You feel like you learned a lot from simply watching SNL closely. Where did you learn terms like “core joke” and other principles of sketch writing?

RS: Right, well I picked up language from the older writers.

BO: But that’s not something I ever heard or thought about, and there’s something kind of evil and wrong about that “core joke” idea, for instance. When people bitch about a sketch where all you see is the skeleton because they take one joke which isn’t that good and they just do every variation on it and you just go, “I get it, just fucking find a new joke, transform it or something.” See, before I went to SNL I’d never even had a sense of that structural awareness, I just thought, “what’s a funny idea and what would be funny to do with it.” Did you learn those terms and principles your first year or do you think you were thinking about those things before then?

RS: Certainly as a young writer, I never thought about sketchwriting as a science at all, it was more like the way you described. But once you’re in the laboratory, everything gets analyzed to death and broken down. It can feel soul-killing, but it’s not like it isn’t informative. You can break down brilliant absurdist stuff to core jokes, too, it’s just harder. But that’s the trick, to make it harder. I did do a lot of things where there was a core joke, but I tried to expand the premises beyond the predictable, or at least get out by the time it got boring. But the bad one-joke sketches really exposed the show, exposed that method for what it is. And then I got to see groups like Kids in the Hall. I came from Second City and I used to watch guys like Rick Thomas and John Kapelos every night. And I watched them develop a sketch and was fascinated and loved that process but I didn’t get to have that luxury at Saturday Night Live. When you’re in a comedy group like Kids in the Hall those guys can start with a core idea but they can play with the characters and they can build with improv, and the sketch ends up having so much more texture. Their sketches, and your sketches, are consistently more interesting because you don’t identify it from the first thirty seconds or a minute, so you’re more on you’re toes. There’s nothing wrong with a sketch that’s one joke – like The McLaughlin group [sketch] – if it’s gonna be that funny and if you can find enough ways to make it build and if you stay ahead of the audience. But if you slip up even a little bit, the audience gets ahead of you and it’s humiliating, and it exposes the worst kind of Saturday Night Live sketches.

II. SNL IS A SPORTING MATCH

BO: Is there anybody you can say you learned the most from about writing sketches?

RS: Jim Downey, I think. I mean, I never ended up writing that much like Downey. What it is more is he inspired me to try harder. He cared so much about being ahead of the audience, and not going with what he called “your first idea” – that more than anything, and the way he would break down and rewrite. Talk in the most specific ways and have it make sense about why a joke was better or why a premise was better. I never felt like I was a lazy writer ever, but I just challenged myself more and more because of him.

BO: I didn’t get hired till your third season at SNL.

RS: December of ’87…Danny DeVito… now it’s coming back to me. That was your first show and you worked on the monologue and you had some funny jokes.

BO: And that’s the third season you were there?

RS: It was my third season. Nowadays I see people bring in their friends so much more often, especially since the Downey regime went away, but you were the only person that I was like, definitely Bob, I can get Bob hired and I would never regret it he is a genius and there is no way that they wouldn’t be lucky to have Bob.

BO: You were wrong.

RS: I was wrong. I was very wrong. You alienated. But they were wrong. I was wrong that they would be happy but they were wrong that you weren’t amazing and whatever happened, you will always have the greatest character piece that’s ever been on Saturday Night Live.

BO: What was that?

RS: You didn’t write it for the show but they only put it on after you left – The Motivational Speaker. I know Chris had moves that you incorporated into that idea but it was your script. And it will always be. You know I don’t think anything will top it, it’s like Joe DiMaggios’ record. It’s like unattainable. I don’t know how anyone will top it. It’s the funniest script ever written. It’s the funniest sketch that was based on a character.

BO: Well that’s nice of you to say. That’s crazy, but nice of you to say

RS: No, no, it’s true. There’s no way, no way that anything could match it. So, you’ll always have that.

BO: That was pure. I don’t know where that came from.

RS: Well, you probably would never have written it at SNL, you were working with Chris onstage at Second City one summer and it was more of an ensemble environment and you weren’t in a hostile place.

BO: Yeah, I couldn’t make it work for me at SNL. It’s just not the way I work.

RS: Well, comedy is about confidence a lot, a lot of times.

BO: Yeah, that place shook my confidence, so hard, so hard.

RS: You questioned a lot of things and you didn’t get a lot of stuff on that you wrote by yourself.

BO: Well, I don’t think they were great pieces. Some of them had good ideas. By the way, I did one of them three weeks ago I did one of the pieces I wrote for SNL twenty years ago. Private Fireman, I did a film version of it.

RS: I don’t remember it.

BO: He’s like a private detective, he shows up when there’s a fire and he wants to talk to you about it. He’s like, “Tell me about the fire. Don’t worry, we won’t rush in. When did you first smell the fire?” And I did it as a film with Paul F. Tompkins playing the guy and I will humbly admit it’s hilarious. You can see it on Youtube, lazypants.

RS: Youtube is for lazypants. That’s my first stop when I don’t want to work. No, second. No, third. Whatever. That’s a funny idea. Some ideas are more films.

BO: Yeah, it is more of a film. But Lovitz would have been funny, I wrote it for Lovitz.

RS: Well, you get to heighten it with style when you make a film because that idea, when you put it in a cold sketch format that’s the same exact look and feel as ratatat sketches that are all joke-oriented. The camera doesn’t get to be a collaborator on the joke, and the camera is a funny participant, and I’m sure you shot it in a cinematic style that heightened the self-importance of the sketch that made it funny.

BO: It’s definitely better. I think, you know SNL is a really tough place to make something great happen

RS: Well, it’s a very limiting. No, it’s just, you are limited by the kinds of comedy you can do on that stage with three cameras. But you can’t shit on a show like Saturday Night Live now, when Kristen Wiig is up there doing things that nobody in thirty-five years has been able to do, which is pull really subtle stuff, create really quiet characters, and make them work in that room. I’m stunned when I see some of the stuff she does because, that was a part of my comedya big part of it, that I never got to flex at SNL, where the audience wants the louder, faster, or topical stuff. Never got to do it in many places since, because I ended up doing cartoons and going to work with Conan where I ended up going back to my broadest childhood instincts, which are just as much fun, but you know I reveled in writing scenes that were quiet and awkward.

BO: Yes, remember your ventriloquist bit? That’s one of the greatest bits ever. Has that ever been done on TV? You gotta do that someday somewhere somehow, you should do it as a short film like that. It would be a great short film, and maybe I could direct it. And here’s another sketch that just occurred to me. Didn’t you write Ross Perot taking his Vice Presidential choice out to a field to shoot him?

RS: Yeah. You helped me with that.

BO: I did not. Your brain is old. Dude, you also wrote, and I did help you with, the Marine Drill Sergeant giving recruits nicknames. So funny, so funny.

RS: Yes, you’re right about my brain, but wrong about the sketch, you threw in some good lines for Perot at the top.

BO: These are all things that you give me credit, it’s very nice of you to give me credit but the fact is there’s a certain element, Robert, if you have an idea that good and you take any three comedy writers you’re gonna come up with brilliant shit. A lot of sketch comedy is that way. A lot of young sketch comedy writers come to me and they wanna know about form – and that’s [important] in sitcom and film – I think in film it matters more – but [in sketch comedy] I always think ideas are more important, way, way, way more important than learning how to construct something. Who gives a shit? Anybody could learn that shit. It’s still good to learn it, but the fact is that’s why I always tell people: don’t pitch me, don’t give me finished sketches or half hour shows or anything, give me three ideas with like a basic riff on it that shows me how it plays out. Because if it’s a great idea, that’s what you need in this world.

RS: I agree but I would, you know, like there are situations where I’ve had to hire people for sketch-oriented shows I have been interested in reading full sketches only because different people have different talents. There are idea people and then there people who can do both, and then there are people who aren’t idea people but can be great at jumping in and I know writers like that who just have a different skill. And they just make my sketches much better, especially if you’re writing a show with a very limited time crunch like Saturday Night Live.

BO: You’re defending SNL there and how hard it is, and it is very hard to do, just on the face of it. People ask, and comedy writers especially ask, “how come the show isn’t better?” I look at SNL as a sporting match, and the question is “how come the game isn’t better?” The contest is; you take this cast, they’re the team, and they compete each week against not being funny. And every time they’re funny they score a point. So every week you’re watching to see if they score a few points. And if they score like three goddamn points they fucking won, you know? But it’s a shame that it’s set up as nothing but this contest because I think the preparation could be overseen better and the show could do more than just score a point or two each week. That’s my grand theory of SNL…but I would add that after years of watching, never directly, just out of the corner of my eye, I’ve concluded that I might be wrong and Lorne might have it exactly right. But we’ll never find out, will we? Sorry, world.

RS: I’m defending SNL based on the way it’s been set up. It’s written in a week and I don’t blame the writers for the compromises they have to make, as far as the process. But, sure, it could definitely be prepared more carefully – you could devote chunks of time to writing and honing nontopical and character sketches. I’m talking about time during the weeks the show is down, when people are either in St. Barth’s or curled up in a ball ordering Chinese food from their bedrooms. You know, more time in the building, more hard work. Everyone bitches about how hard the show is, but if there were more sketches in the bank, the actual production week would be less stressful and dramatic. Not as much fun to tell Tom Shales about, but more fun to watch at 11:30. That’s the answer. You’re welcome, world. By “world”, I mean Bob.

III. PURE EGO

BO: What was the first sketch you feel like was a powerful sketch. Was it the Shatner one?

RS: Yes. That was the first time, but still, you know, it’s like a curve. I mean, the first sketch I was really exhilarated by was this standup comics sketch in my first year, with Tom Hanks, where they all talked like Seinfeld rip-offs. It did really well and I was so excited – I went home and VHSed the show and I literally watched the sketch five times at four in the morning after the party. I just could not believe that this happened, that I had made so many people laugh. And not in an important way, this was just pure ego. Just, wheeeee, look what I did.

BO: So the Shatner sketch –

RS: The Shatner sketch was a whole new level, a dream. To write something that was that resonant… And again, that’s the problem with the type of comedy writing where you’re just trying to find observations. Because then everybody just observes things a million times, a million other ways, and it just doesn’t seem that interesting. You watch that scene and it’s still very funny—just because you can’t believe William Shatner’s doing it. And he’s so subtle, he’s not goofy doing it, he’s very gentle. And we wrote it, we ramped up nice and slowly to it, which George Meyer helped me do.

And, you know, that moment, that “get a life” moment, was something I hadn’t experienced, where like now I’m actually doing something that strikes such a resonant note with the audience that it’s working on a completely different level, not just being funny. But before that show I had an incredible night the show before, on the Three Amigos show where I wrote two sketches that are—well one of them is a very famous sketch for people who are fans of the show. It’s the sketch where Ronald Reagan was a genius.

BO: Oh yeah, what’s it called again?

RS: I called it “Mastermind,” and it was my idea but everybody was excited about the idea and I had a lot of help—George [Meyer] and Jim Downey and Al Franken all jumped in on it. I was proud of it because it was a way of making fun of comedy that wasn’t mean-spirited and wasn’t direct – it was a trick.

BO: Such a smart piece, “Mastermind,” where Reagan is befuddled and slow, but pretending, and then its revealed that when he steps backstage he’s incredibly sharp and on top of everything. And it was a really great thing because people laughed at how dumb he was then they laughed at the notion of, no, what if he’s really smart.

RS: It was just a “fuck you” to the premise that he’s dumb and how tired the premise was. I mean they were still laughing because they believed he was dumb but just the idea that he was a genius was so much fun to see.

BO: I want to say that when I think about your sketches, just those two sketches, “Shatner” and “Mastermind” – you know there are certain people at SNL who we both like who are writers who write really silly stuff, right? Great, genius silly stuff, Jack Handey, Andy Breckman, and I think George Meyer. And everybody writes, all those people write different things. But you, I think you had – and this is why I said that one thing in the SNL book where I said you saved sketch writing – because to me, those two sketches have commentary in them: they’re silly, they’re performance, they’re smart, but they have commentary in them about people and the way they think, or some phenomenon in the world—you know nerds at the Star Trek convention and the phenomenon of that—and yet they don’t exist solely to do that. Now, some of Jim’s pieces and they’re really, really funny, but they’re supposed to be commentary pieces. They can have silly aspects to them. But you’re stuff was more than commentary – really smart, a bit removed, not really with a simplistic point of view, but always cloaked in comedy, comedy, comedy.

RS: Well, I think you just nailed it, the three rules of comedy. “Comedy, Comedy, Comedy.”

BO: That makes no sense.

RS: …think about it some more.

BO: (thinks) Nope…still not making sense.

RS : Whatever, man. They’re your rules.