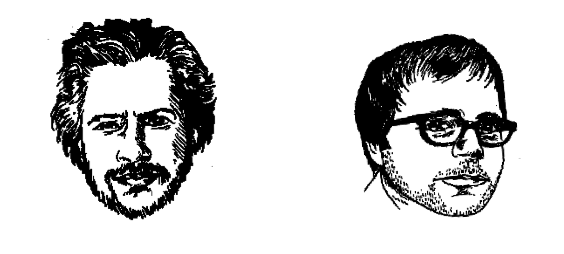

Ben Gibbard fronts Death Cab for Cutie, a band from the Pacific Northwest whose moody, rigorously introspective music rose up in the patch of scorched earth left by ’90s alt-rock behemoths Nirvana and Pavement, coming into play as a sort of post-millennial soundtrack for young people. After releasing several successful records on indie label Barsuk, they made the decision to enter the major label arena in 2005, releasing the wildly successful Plans on Atlantic Records. Gibbard also shares songwriting duties with laptop innovator Jimmy Tamborello in the Postal Service.

Wayne Coyne has been, for the past quarter-century, the central creative force behind the Flaming Lips. Their most recent album, At War with the Mystics, finds them at war with contemporary popular music, as they retool and reverse-engineer the form with an invigorating recklessness. The Lips’ determination to make music as vast and cataclysmic as a Venusian storm front will not surprise auditors of albums such as In a Priest-Driven Ambulance, Clouds Taste Metallic, or The Soft Bulletin, but the crazed vocal harmonies and startling atmospheric flourishes of At War with the Mystics remind us that we haven’t yet mined a fraction of what’s possible in rock.

The following conversation occurred by phone; Coyne sat in a hotel room in San Francisco, having just taken part in the Noise Pop festival. Gibbard had just arrived in Austin as part of a tour of the Southwest.

I. ARENA ROCK

WAYNE COYNE: Hey, Ben. I’m sitting here in San Francisco.Where are you at?

BEN GIBBARD: We just pulled into Austin about fifteen minutes ago. We’re in the midst of our first full-production, arena-style tour. We’re carrying a PA and all that kind of stuff, and we’re co-headlining with that band Franz Ferdinand—

WC: Oh, right—cool! Do you guys play after them?

BG: We’re flip-flopping. It’s kind of intimidating, playing after a band like that, because they’re so high-energy. We have our rocking moments, but we’re nowhere near as high-energy as these guys are. But I’m getting this impression from the crowd that people are coming to see us be us, and to see Franz Ferdinand be Franz Ferdinand. I think that we’re both learning about ways to integrate the other band’s elements into our own, to kind of make the show seem more cohesive, if that makes any sense, you know?

WC: Well, right. You want to make the whole show good. That’s what I think bands forget a lot of the time, that you don’t want the opening band to suck. You want the opening band to be good. You want the whole night to be good for the audience, not just your ninety minutes of stage time. It sounds like you have an interesting bill. Do you guys feel like you’re sort of becoming arena rock bands?

BG: You know, I think the whole experience for us so far has been very surreal and—I would never want to say “uncomfortable,” but I think that we’re all kind of trying to determine whether this is something that we want to pursue on this level. I mean, Franz Ferdinand is a huge, massive band that’s known all around the world, and I think that coming to the States, for them, is kind of a step down from what they’re used to. Their shows are kind of geared toward bigger venues, and while I think that things are going pretty well for us so far, by the time we’re done with this tour we’ll have a better understanding of the kind of venues that we want to play. Because you guys could, if you wanted to, probably walk into San Francisco and play, you know, the Bill Graham, and sell it out, and I’d pay, but it seems like—

WC: Right, I know what you mean about the bigger venues. All the logistics of “how much do you sell tickets for?” You know, I still feel weird when people have to pay thirty-five dollars a ticket. You’re kind of like,“Oh, damn.” And a lot of people think that that’s a great price.

BG: We’ve been just looking around at bands that are around the same size as us to determine who’s on the high end, who’s on the low end, and trying to come up with something in the middle, where we’re not totally cutting our costs to the point where we’re losing money, but where we’re also not raking people over the coals.

WC: I think that that’s the perfect way to do it. I’m always surprised that people will buy a fucking T-shirt for thirty dollars. You know,it’s just a damn T-shirt,but then I’ll easily go to the movie theater and watch some dumb Hollywood movie and buy a bag of popcorn that costs six dollars, you know what I mean? And I think, well, that’s fine. And then I’ll go down to the store and buy a fucking bottle of water for two dollars, you know? It’s water, Ben—you know?

BG: Yeah, you know, the six-dollar bag of popcorn, it’s kind of built into the experience of going to a movie theater. It’s going to be ten bucks to get in, and it seems kind of futile to say,“Ten fucking dollars to get in? Are you kidding me? There’s no way.” There’s no point to even bitching about it, you know? That being said, it can get out of control, like when you know you’re paying three hundred dollars for the Rolling Stones—

WC: People do it, I know! I mean, I wouldn’t do it. But people do it and they do it sort of gladly with, like, some sense of pride, like “I paid three hundred dollars just to see the Rolling Stones.”

BG: Yeah. At the same time, though, I know enough people who would pay that much to see them, who would say, “You know, actually, it was worth every penny because they were the Rolling Stones.”

WC: I think it comes back to that experience. They to go to some place where Mick Jagger is actually standing, and he cares about them, and maybe that’s what matters, you know, that it’s whatever you make of the experience. So let’s hope some of that is working for you and me, right?

BG: I hope so, yeah. [Laughs]

II. THE SANTA SUIT

BG: Even though the profile of our band has sort of grown over the past couple years, my opinion of myself hasn’t really changed one bit, but it seems like people— and I’m sure that you probably get this even more than I do—like, you know, you walk around in life as a pretty normal person, and then all of a sudden it’s time to climb onstage and there are thousands of people there who see you as more than just Wayne Coyne, you know?

WC: I think most crowds still think that rock stars are born, and then they’re just carried around on pillows all their lives, and then there are the regular people who just get what they deserve. And you and I know that we just do it because we like it, that it’s just dumb luck that these people like what we do, and we just go with it. And maybe our audience knows that too, but I just beg them to play along. The reason that people love the Rolling Stones shows is that when the Rolling Stones come onstage people go crazy, like it’s the greatest thing that ever happened. And I try to play up our shows that way. If we make our show seem like it’s the greatest thing that ever happened, it’ll just be a lot of fun. We know that it’s not the greatest thing that ever happened, but if we act like it is, we get to do that thing. And so I just beg them to play along, like we’re the greatest cultural event that ever happened, and, you know—

BG: And a lot of times Flaming Lips concerts are the greatest concerts that have ever happened.

WC: [Laughs]

BG: I mean, I really—I feel bad for any group that has to go on after the Flaming Lips because I don’t think that there is any band that can compare with the experience that you give the people in the audience. I just can’t believe that you guys can pull that off—that any human being can pull that off. I remember the first time that we ever played with you guys at this festival in Spain, maybe four or five years ago. I remember watching you guys and being like, wow; it was as if this guy Wayne Coyne came off a spaceship and landed onstage, played the show, and then was beamed back up. We were watching your DVD, The Fearless Freaks, in the tour bus, and we were all talking about how we’d always wondered things like, “I can’t imagine Wayne Coyne mowing his lawn, or doing his nails,” and you put it all out there in the film. I was really impressed with the amount of access that you were giving Lips fans to your personal life. I mean, you go so far as showing the cross streets where you live.

WC: Maybe we’ll live to regret that, but, you know, most of the people in Oklahoma City who would be watching that movie already know where I live. It isn’t one of those cities where there are a lot of people coming through. I’ve thought occasionally about some kid driving from Chicago to Los Angeles feeling compelled to stop by—but, you know, I’ve done that same thing. I remember we were on tour and we were going to be driving through the town where Dr. Seuss lived, and I thought, “We should drive by his house!” I thought, “Maybe he’s going to be out there mowing the lawn or something.” Me and one of my older brothers, we were going to drive up to New York to see if we could spot John Lennon walking around Central Park—just a couple of months before he got shot. So I can see where people—and I don’t look at myself as being some fanatical weird fan—I just think it’s interesting to see, “There’s their house, and that’s what kind of car they drive, and look, they got some trash over there on the side of the house that they haven’t picked up.” Anything that gives you a bit more insight into what they’re really like.

BG: I would assume from the movie and just from what you’ve talked about now that you’ve had people roll up on your house. How do you deal with that?

WC: Well, the analogy I use is, let’s say you’re at the shopping mall with your girlfriend, and you guys have a fight. You know, you’re arguing about something—you know how those things go—and some friend of yours comes up that you haven’t seen in a year and is like, “Hey, Wayne and Michelle, how’s it going?” You just pretend that you’re not really fighting. You get through it in the best way you can. You say, “Hey, good to see you again!” and then when they leave, you get back to your fight, you know? And, in a way, I look at all these people, these Flaming Lips fans, as someone who, you know, they kind of know me. I’m putting music out there, I’m telling them about my life, I want them to know me. I want them to be fans of our ideas and our art or whatever, and so it doesn’t surprise me that they might think,“Hey, I know that guy, and I’ll just go up and say hi.” But I take the responsibility of saying, “It’s up to me to deal with them.” It’s not their problem of how they deal with me, it’s my problem of how I deal with them. I should be the one who knows how to handle it. And so I treat it like: if I was going to meet some rock star that I really liked, how would I want them to be?

BG: I really kind of envy that position you’re able to have, because I just find that whatever mood I’m in, whether I got enough sleep the night before or whether or not we had a bad show, or let’s say I had a fight with Joan on the phone, or whatever else, I tend to let that affect the way I deal with people.

WC: Sure.

BG: And I’ve sometimes felt, when somebody walks away, that they didn’t get the experience they wanted from me, you know? And not in the sense of like, we’re not going to become best friends, but just, maybe I was a little curt, or I didn’t, you know—

WC: In the end I kind of look at it like, what did you want when you met Santa Claus for the first time? You didn’t really want to know that he was just some guy who was lucky to have a job being Santa Claus for two months around Christmastime. You wanted it to be the real Santa Claus. And at some point, you and I, we put on a little bit of the Santa Claus costume and go out there and do the show. So I can look at it like, if I met Santa Claus, would I want him to be tired and grumpy and say, “Hey, little kid, leave me alone, goddamnit”? I would want him to handle it and let me walk away with that image and that belief still in my mind. And so, I don’t know,I think in that sense I always feel like I owe the audience. Someone comes up to me, you know, I owe it to them not to have bad breath and be grumpy.

BG:Tell ’em,“Get the fuck out of here, I’m eating,” that kind of stuff?

WC: Well, right. You know, and I’ve met people like John Waters, where I walked away from meeting him and he’s perfect, just the way I wanted him to be. It just seals it in your mind forever when you feel like you’ve smelled them and you’ve touched them, that they are what you thought they were going to be. And then there’s other people that you meet and just, frankly, don’t even like, and I would never want that to happen to this great thing that’s become the Flaming Lips, I would just ruin twenty-five years of all these great accidents and all these wonderful things that have happened to us in two seconds, when someone says,“Ah, fuck, he was a dick. I don’t like them.” I value every fan—they’ve given me this life, and if they want to talk to me for a couple of seconds, no big deal, right?

III. GERMAN JOURNALISTS

WC: Do you still have awkward moments when people who are interviewing you ask about things you don’t feel comfortable answering?

BG: At times, but I kind of feel like I get a read on people pretty quickly as to how the interview’s going to go. When the first question is “How did you get the band name?” and the next question is “What are your influences?” you kind of get a sense of how the interview is going to go, and you can only give them so much. But when I start talking to people and I find that there’s a rapport and they’re intelligent and they have a similar sense of humor, I don’t feel that there’s anything I really feel uncomfortable talking about outside of broadcasting where my family lives and stuff like that. Or when we’re in Germany, and we end up answering questions in translation like “So your last record was one of the greatest records ever made by mankind. Your new record is—‘swill’? Am I saying this right? ‘Swill’? How do you explain why you made such a horrible record after making such a great one?” And we’re like, “Well, I don’t really know how to answer that question.”

WC: I know! Fucking German journalists! They don’t even realize how real that is, and I don’t think they know that they know that they’re being so fucking harsh or so critical. They just act like,“Well, I’m telling you the truth, that’s what you want to hear. ”And you’re like, “Well, fuck.” I was talking to one guy, and he actually said,“Excuse me, I need to take a shit very bad, so it will take me a couple of minutes.” You know, if I need to take a shit or something, I just say, “I need to go to the bathroom,” or whatever, but he was like, “Excuse me, I have to take a shit and it will take me a couple of minutes.”

IV. THE MAJORS

WC: Well, you guys have done it. You guys have done it, man. I mean, when people come to your shows and people see you, even when people read about you and stuff, you guys have really done the thing that I was hoping would happen: that it wouldn’t be like, “Oh, everybody loved us when we were on an indie and now we’re on a major and you see the disaster that’s happened.” You guys just sort of seamlessly said, “We’re doing our thing and it’s just not going to matter.” And it’s just worked perfectly. That’s the secret—the secret is that it could have gone—

BG: Oh, without a doubt, it could have been a horrible mistake.

WC: And you guys could have just said, “Oh, the majors suck, and nobody knows what they’re doing, and the world sucks,” and all that. And the other side of it is that you have to sign up for the work, you know, the work starts.

BG: I think the most important thing about making a transition like this is not looking back. Or maybe “not looking back” is not the right term, but doing it unapologetically, to say, “You know what? We want our band to be successful, and we want people that haven’t heard our music to hear it.”

WC: And this idea that the major labels are obviously the enemy of indie music—well, whoever still believes that is obviously tripping anyway. It’s just not real. Each band seems to take control of their own destiny more than anybody gives them credit for. And that’s the part of it that I like about you guys—that part of the story doesn’t really seem to matter anymore. It’s really about you guys, and the major label and the indie part—who cares? It’s you guys and your music making it work. It’s not about a label making it work, it’s you guys and the audience.

BG: I can’t imagine what it must have been like for you guys starting out when the indie labels were these seemingly way, way, way left-of-center kind of entities that put out records and there was no way to get your music into any—

WC: You know, I don’t think we even considered major labels or anything like that. I think our biggest goal was to be on SST Records. We never dreamed that it would be anything else. I didn’t even know what a label was when we started. I just thought that there was this band with music, and what’s a label, what’s a promoter? I didn’t give a shit about that, I was just a guy in the audience who wanted to make music, you know? And I think that most of the audience is still like that. I think that when people go on about labels, and about radio, and all that, I think that most of the audience is like, “What’s all that? Who cares? I thought it was just about sex, drugs, and rock and roll.”