MCMANSIONS

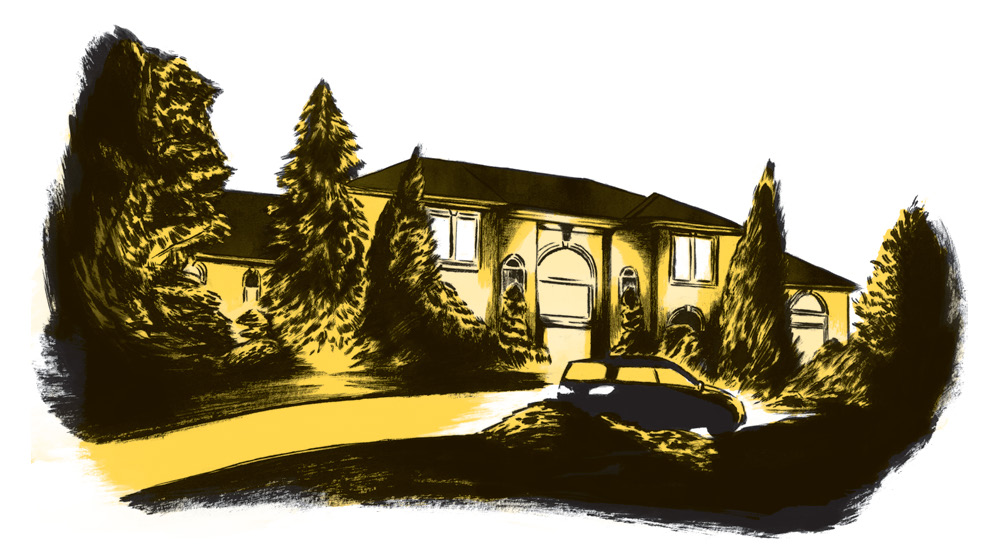

I’m driving past the dilapidated red barn on Pleasant Valley Road on the border of Marlboro and Colts Neck, New Jersey, ferrying my seven-year-old daughter to a pool party at Joey Martinelli’s house. The view is of tree-stripped low hills punctuated by colonies of pop-up McMansions, hastily built in the aughts and faced with Dryvit. Scattered among them are the remains of nineteenth-century Dutch farmhouses and Revolutionary War battle sites. There are no mature trees in McMansion Land, no; those are only in the distance, far away but there, still. This is Monmouth, the northernmost county of the Jersey Shore, one hour south of the Holland Tunnel, exits 128–117 off the Garden State Parkway.

On the Martinellis’ block, the yards are all meticulously landscaped, replete with topiaries, emerald green thuja arbor-vitae pruned in spirals, and the occasional stone lion. The street names betray aspirations they don’t quite reach: Lecarre intersects Coleridge Drive; Huxley Court runs parallel to Blake. Barbecue and grass cuttings commingle in the breeze.

“You didn’t bring Dunkin Donuts, I hope,” Jamie Martinelli calls, standing in the frame of her enormous front door. “My bulldog is allergic to gluten.” Jamie has long corn-flower locks, eyelash extensions, and muscles. She is genuine, informal, and inadvertently in-your-face—which is to say, flamingly Central New Jersey.

“Nope, I just brought Ellie.”

“And a birthday present for Joey,” my daughter adds. Guests are arriving. The bulldog, wearing a hot-pink leather collar, squeezes by Jamie, running floppy-tongued and respiratory to greet them.

“How cute is this dog!” says Jamie’s neighbor, elongating the aw in “dog.” She is dressed in a black leotard and sequined sweatpants—for an event, she explains. Her family runs a bar mitzvah dance troupe. The bulldog jumps like a spring. Kids swarm. It’s a cacophony of hellos, loud as an Italian dinner. I get a bear hug from the guy who recently designed Jamie’s bespoke home garage. It’s a marvel of sleek organization, with epoxy-coated floors, overhead storage, and slate-colored cabinets. He also coached my son’s team in Little League. Under the cathedral ceiling, two dads swap tips about where to find sales on leaf blowers. What does Bespoke Home Garage Guy talk about?

I wonder, so I linger. I overhear something about barbecuing and Peter Luger’s sauce. Then he turns to kibitz with another dad about his business delivering drums of equipment to stadiums. Jamie Martinelli gestures over the din, responding to the admiration of her family portraits—taken on the beach and mounted in ascension along the twin winding staircases. The Martinellis own a scrap-metal recycling plant. What other people throw away has made them millions.

The McMansion Tribe knows how to make a living, not by trafficking in inherited money, tech money, or private-equity money, but by dealing in old-fashioned cash. They’ve cleverly devised ways to offer recession-proof goods and services. They’re Trump supporters too: 53 percent of Monmouth County residents voted for 45.

It’s a very different world from the one I inhabited in Manhattan. There, strangers assessed one another but didn’t make conversation. I don’t miss that. In Central Jersey, the people are TMI friendly and unguarded.

The people at this party are not, of course, the mythical working-class white Trumpers, but their parents are. Mine are, too, so I know how it is that this crowd identifies with the president. Like he is, they’re derided as tacky, and like he does, they value a code of loyalty. À la Trump Tower, Central New Jersey McMansionville is the Place of Too Muchness—too much marble, too many mirrors, and oversize archipelagoes of kitchen islands. There are plenty of local middle-of-the-road Democrats, but Monmouth is hardly a liberal hotbed of resistance. Hillary Clinton, with her Yale Law degree and frumpiness, just wasn’t relatable here. Me? I’m left of Lenin. Even though my politics make me an outlier, it feels unpretentious here, almost comfortable.

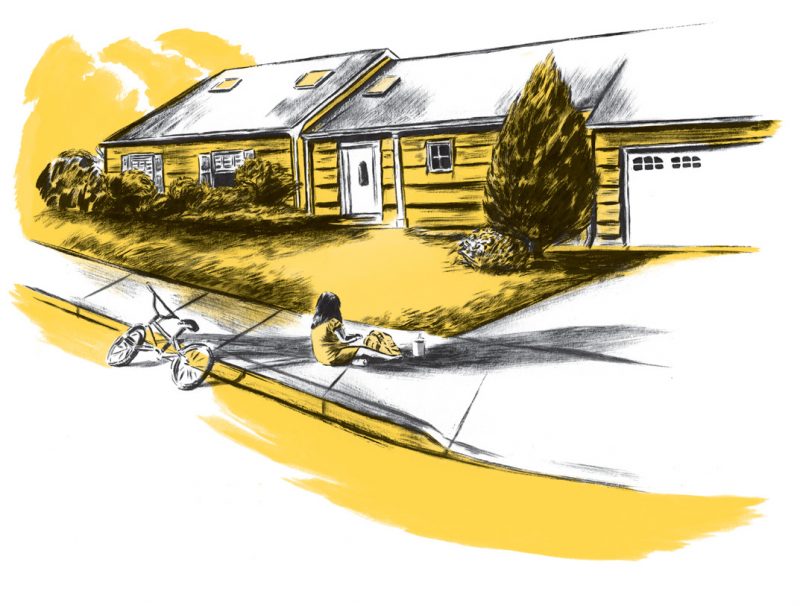

WHITTIER DRIVE

I grew up on the other side of Route 9—the modest part of town—where many families have lived for generations in what is still a Levittown-like development, the proverbial little boxes on the hillside made of ticky-tacky. This was before the real estate scandal of the ’90s, when then mayor Matthew Scannapieco took bribes from developers and the number of housing units rocketed by 40 percent, ushering in the McMansions. More recently, there has been an influx of immigrants from the former USSR. Across the street from my childhood home, where I landed postdivorce with my widowed mother and my kids, are Serge and Svetlana Gertsberg. Another Russian family just moved in next door. And my mother brings my daughter around the corner to take private art lessons in the home of an elderly Ukrainian cubist named Val.

“There are three types of Jersey people,” according to my dog walker, who has a tattoo of the state on her forearm. “South Jersey is slow as sap. Central Jersey is laid-back. It’s North Jersey that’s classy,” she says, obliquely commenting on Serge and Svetlana’s Central Jersey side yard, where they have erected a grouping of permanent pull-up bars for their boys, a mini ninja warrior course.

This isn’t cultured Montclair. It isn’t the intellectual hot-bed, Princeton. Nor is it the wilds of the Delaware Water Gap or John McPhee’s Pine Barrens. This isn’t Elizabeth, across from the jewel of Manhattan, exhaling emissions like a pipe organ with a bad attitude. We’re not quite in the hors-ier region, either: Bernardsville, Bedminster, or Tewksbury, where people go to get their Barbour jackets waxed. This is the maw of the state, where a couple’s night out is black-jack in Atlantic City and a shopping mall get is Steph Curry high-tops for the kids.

Grandmas are the unsung heroes of Whittier Drive. My mom let her grown daughter and grandkids move into her home. In the house next to ours, Ginny Hogan, a retired gym teacher, lives with her daughter, four kids, and three dogs. Across the street, Jackie and Sean Strang converted their garage into a bedroom for Sean’s mom. Living with Grandma is a thing again on Whittier, where economic necessity reigns.

One weekend night, my kids and I go to dinner at TGI Fri-days with the Reyeses, a Filipino family from down the block. Dana Reyes is a receptionist at a doctor’s office. Her husband, Leo, is an electrician. He grew up in the house they live in now. I vaguely remember Leo from high school as a friendly, quiet guy on the wrestling team.

“This house was our Ellis Island,” he tells me when I ask about his childhood here. “At one point, there were twelve to fifteen of us in this twenty-two-hundred square foot home. Come on, get in the van!” I climb into the third row of the family’s conversion van, complete with curtains on the windows and an elevated roof. Leo and Dana seem far away in front. They ought to put a disco ball in this thing. My son sits with their son, Paolo, his best friend; my daughter sits with the younger Reyes twins. “I’m warning you, and I don’t want to fight about it,” Leo says, craning his neck. We lock eyes. “Fridays is on me.”

Whittier Drive is the kind of place you have to leave at a certain time in your life, or else you never will. The Armenian woman across the street, who babysat for me when I was a toddler, sold just last year, and the McGeehans, two houses down, recently went too. Pat McGeehan died a month after they moved out. She had been a math teacher in my middle school. Her husband was on the board of education. Their redheaded son was at my school bus stop. Our birthdays were eight days apart. I can’t believe it about Pat, yet somehow, I can.

THE SHORE: REVIVAL

Any talk of New Jersey must include the 140 miles of oceanfront, from Perth Amboy to Cape May Point, otherwise known as the Jersey Shore. There’s Long Branch, with the imported palm trees of Seven Presidents Beach, and Red Bank, on the Navesink River. Asbury Park, anointed the new “it” gay hangout, feels like Coney Island with a facelift. You can see the Melvins at the legendary Stone Pony or do your wash at the Razzle Dazzle Laundromat, right across the street from the storied music venue, the Saint. Inland, in Neptune, women in fabulous hats can bring their Sun-day hallelujahs to the Victory Tabernacle of Prayer, where they can hear Pastor Everniece C. Carlisle.

Hurricane Sandy came roaring through New Jersey the year I limped back, raw from divorce, so it was easy for me to relate to the ravaged towns and lives around me. Tele-phone wires down everywhere, power out, homes destroyed, mold invading. Post-Sandy, the years of ridiculing the Jersey Shore reached a tipping point and became distasteful. Restoration and rebuilding yielded a sea change in New Jersey’s self-perception from shame to a mild swagger. It’s no longer Snookiville. Call it a revival. And to me, the transformation feels personal.

Last summer, I went through chemo. My friend Dolores still picked me up every morning for the gym. “You got this,” she said. The Reyes Family watched my kids, even took them for overnights. On my non-chemo weeks, I’d sometimes drive to Mary’s Place by the Sea, a nonprofit beach house for women with cancer in Ocean Grove, between Asbury Park and Avon. In this turquoise refuge filled with summer light, we women did guided mediation, got Reiki massages, and took yoga classes at sunset. We fed on healthy, vegan meals sourced from Jersey farms. There, with new friends from Old Bridge, Holmdel, Belmar, and Spring Lake, I healed in a community that was healing itself. We strolled the brand-new Trex boardwalk, stopping for a detour at Asbury’s Convention Hall, where kiosks sold artisan-made jewelry and letter-press stationery. This is it, I realized. The New Jersey my dog walker memorialized on her arm. The Jersey Shore as Comeback Kid. The reason Jersey Strong has fast become a popular bumper sticker. If you have enough support, disaster can make you tougher. It can be an opportunity to create yourself anew. Kicked to the wall by nature, degraded as an armpit by Manhattanites, the Jersey Shore is rising with the assistance of FEMA bucks and the can-do, never-say-die essence of its residents. We are living out our second chance.

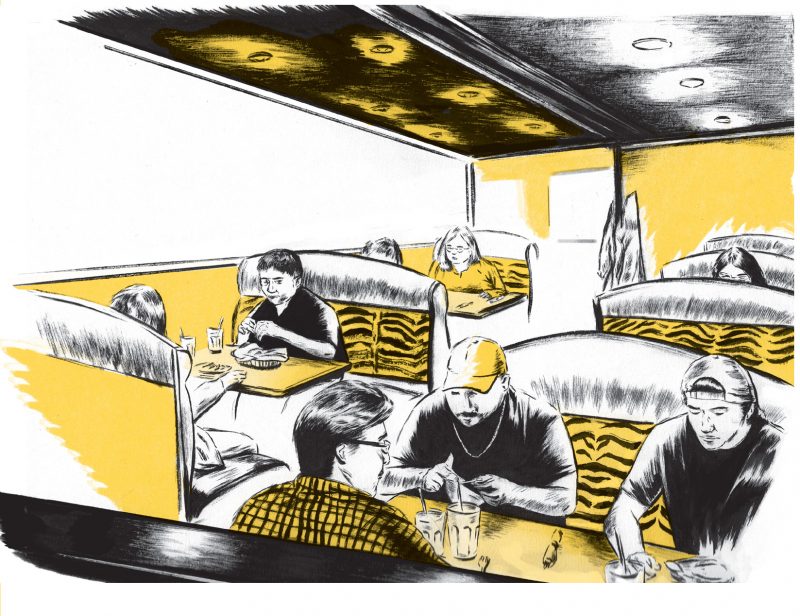

THE DINER

The grumble and hum of the industrial dishwasher in the back of the Marlboro Diner, a half mile from my childhood home, is the sound of Sunday mornings. My kids and I hang our coats on the little hooks and squeeze into a booth. Then we thumb through the laminated encyclope-dias of our menus. Both kids order chocolate-chip pancakes, which turn out to be as big as their heads. I can feel my dad, fourteen years deceased, in the air. He would tell the wait-staff precisely how to scramble his eggs. “You gotta constantly stir ’em. I like ’em real soft.” There’s even a story about him

grabbing a line cook by the collar after sending back his eggs twice. “This isn’t scrambled. This is a chopped-up omelet!” When you grow up in New Jersey, diner memories are folded into your limbic system. The Manalapan Diner, my high-school hangout, has recently undergone a Gustav Klimt–themed makeover. The servers wear a reproduction of The Kiss on their ties. Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks would have made at least some sense, but who thinks “diner” and Klimt?

The menu devotes an entire page to a celebration of the décor.

New Jersey boasts over six hundred diners,

but your go-to diner is always the one within a mile of your house. The white, lit-up sign for the Marlboro Diner is bigger than a marquee, smaller than a billboard, and juggles various typefaces. This diner shares real estate with a Russian LLC, “Joseph Youssouf, Attorney at Law,” and the Marlboro Motor Lodge, where rooms rent for sixty-five dollars a day or fifty dollars for four hours. Apparently they also rent by the week, because there’s a flag draped over the metal railing by one of the first-floor rooms, and potted plants, a scraped-up bicycle, and a faded garden gnome outside another. The motor lodge has always been here, but I never paid attention to it before returning to this neighborhood as a parent. “My bus stops at this place to pick up a kid,” my son has informed me. “He’s an Indian boy who sits alone in a two-seater. But he has an iPad. He plays with it on the bus.”

Inside the diner, there’s not a Klimt to be seen. It is twentieth-century blah, not the quilted stainless steel of the ’50s “Valentine” diners nor the old railroad-car style of the ’30s. The brown-and-black vertical-striped awnings shout “no-frills.” The place is utterly without illusion. Which is its charm. At the next table, a couple is loudly reminiscing about the food on their Royal Carib-bean Cruise.

Young guys from Guatemala and Mexico wipe down the tables. They are seasonal employees who live in the aging clapboard houses of Freehold Borough and Keyport and travel to work at the diner or the car wash or to mulch the wealthier neighborhoods via the sighing buses of New Jersey Transit.

CUZIN’S SEAFOOD CLAM BAR

Cuzin’s! It’s an empire of seafood, a clam bar in a strip mall with valet parking. Rustic reclaimed barn wood meets modern. Dozens of naked bulbs on pendant cords hang at different heights. Big-screen televisions blare above the neon-blue bar where we wait for our table.

“It’s like a cruise ship married a casino

,” my poetess friend says. She is visiting from New York and requested “the full Central Jersey dining experience.”

I’m happy to oblige her.

“The place really is owned by cousins. That’s one of them,”

I say, pointing.

“He’s so tan,” she says. A thick-necked guy sends over frozen drinks.

The bartender tells us not to mind him. “He just got out of college.” He winks.

“That means prison,” I whisper to my friend the way people whisper, “

Cancer.”

“How De Niro!” she says.

We are finally seated. My friend starts with the colossal crabmeat cocktail. The seafood arrives on towers of ice. We order and order. Swiss Alps of pasta meet the Lesser Antilles of fresh clam platters. I devour the pappardelle carciofi, a small country of roasted artichokes and spicy sausage over pasta. In this eatery of swank-meets-sleaze, you have to remind yourself to turn off your judgment brain and just open your mouth, because the food is perfection.

Groups lounge on banquettes doing shots of Cîroc. A female server in a white-collared shirt over a black leather corset smiles and weaves through the crowd. The bass beats in my ears. Cuzin’s is not fundamentally different from the trendy restaurants-cum-bars in Manhattan. The clothes are couture there and too short and tight here.

Cuzin’s Seafood Clam Bar is tastier than Central New Jersey’s chain restaurants, diners, red-sauce Italian, or take-out Chinese. And the clientele is a damn good time. They let it all hang out, with their family and friends, their meat-balls, their Parmesans and their Cadillac Escalades. Every-one knows each other at Cuzin’s and the steaks come thick and juicy. My dad, a wholesale meatpacker, would have loved this place. These are his type of people: loud, hungry, and ready to laugh. It’s easy to imagine my parents here on a date, dressed up, my mom with her one glass of zinfandel, my dad with his prime rib.

We pay the bill in cash because everyone else seems to. Twin bags of takeout go home with us. The valet brings my Subaru and I slip him a five. He opens both the passenger- and driver-side doors, chariot-style.

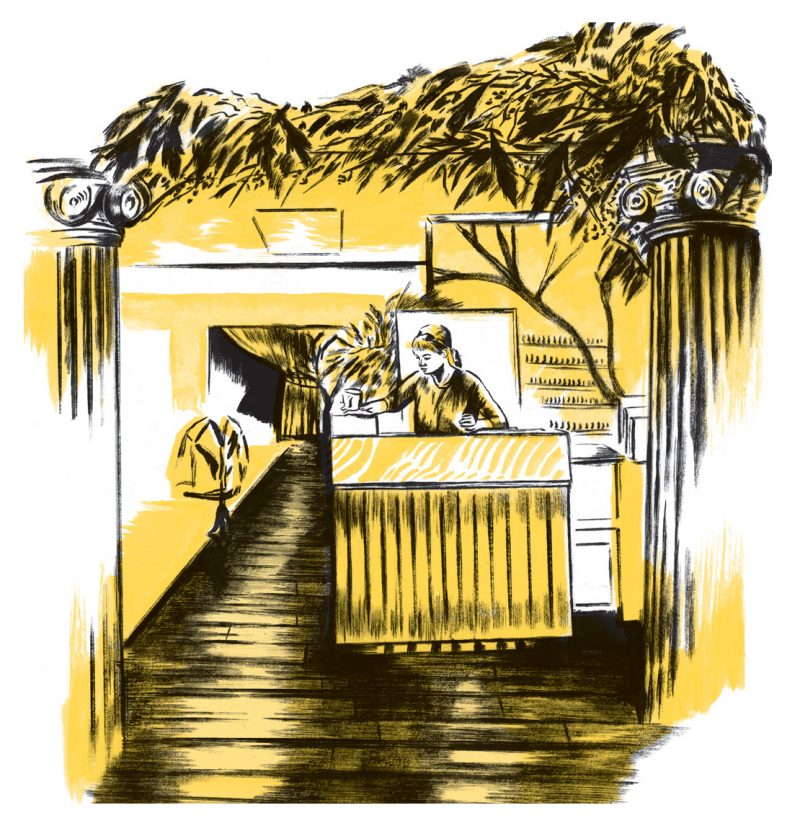

AVANTI DAY RESORT

I’m getting them. Fake eyelashes. Billboards up and down Route 9 advertise the Avanti Day Resort as “The Perfect Gift,” so on a weekend when my ex has our kids, an appoint-ment at Avanti is my present to myself. A snow globe placed over any three-mile radius of Route 9 would contain a big-box store, several tanning salons, and, of course, a sprinkling of diners. Strip malls eat up the farmland in a mash-up of all things retail. A Smoke Ringz vape shop sits a few stores down from the Foc

accaria —which is a restaurant devoted to Italian bread. Nestled in the corner of this shopping center is the Avanti Day Resort.

What is a day resort? Evidently it’s a three-ring circus of beautification right off the highway: there’s a boutique in front, a salon in back, a spa on the side. I walk beneath a tinseled trellis to enter. It’s like a holiday wonderland. The boutique is crammed with such gift items as pomegranate-scented candles, seventy-dollar shampoo, wool ponchos, and cubic zirconia studs the size of dimes. A woman with a cascade of bouncy blond curls chats me up as if we know each other. Think Dee Snider from Twisted Sister hawking ruffled baby bonnets. When I don’t seem interested,

she pitches bejeweled flip-flops.

The salon buzzes with action beneath colorful stalactites of Chihulyesque light fixtures. Stylists do “calligraphy” cuts, highlights, lowlights, the balayage technique, Japanese straightening, “Magic Sleek hair de-frizz.”

“This new guy I’m dating wants to take me to DC on Saturday,” I overhear one stylist telling her client.

“The museums there are free.”

The stylist waves her comb. “I don’t like museums!” I hear her say. “‘No learning,’ I told him. ‘It’s the weekend!’”

I cut through the manicure section

. Russian, Polish, and American-born technicians apply glitter, gel, and ombré polishes. On the list of things New Jersey is good at, nails are at the top.

I duck into the spa through a drape of red velvet. Tinkling music, a gas fireplace, and a muted television tuned to underwater sce

nes surround overstuffed, garnet-colored sofas. The massage tables in the treatment rooms are illuminated waterbeds. I pour myself something with cucumbers floating in it, grab a handful of dried apricots. then head over to the eyelash lady.

She wears magnifying glasses and shines a bright light on me while I lie back. It’s a little like visiting the doctor. She wields metal instruments and examines me.

“My technique is the best around,” she brags. “You’re going to be spoiled.” I hear about her eyelash-application education, which is extensive. Her husband is the mayor of her town. They are always entertaining. She has to get out of here early today because a guy is coming to install twin chandeliers in their dining room. Eyelash Lady lives larger than I do, for sure. And when I check out of Avanti, I know how. The lashes cost five hundred dollars and I didn’t even go for the mink. Mink eyelashes!

“You need this cleanser and these applicators and this crystal-drop coating. This is the bare minimum for my lash-ex-tension upkeep.” She hands the products to me in a black tulle drawstring bag, and I drop another hundred dollars. At these prices, I know I won’t be back “every two weeks for maintenance,” but I love my lashes. I feel like a real Jersey girl.

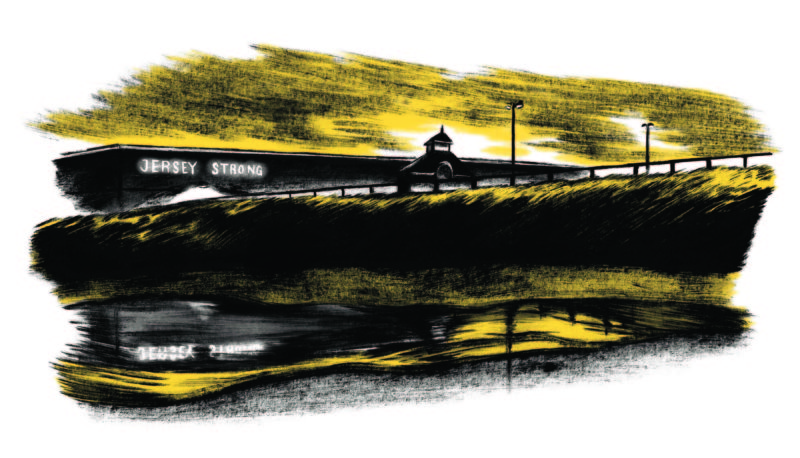

JERSEY STRONG

My friend Dolores and I are side by side on treadmills. She is wearing her Giants jersey and is tuned in to the game as she strides up the incline. I’m listening to my running mix. We’re in an amphitheater of exercise that was known, until a few months ago, as WoW or Work Out World, now rebranded as Jersey Strong, a nod to a rising tide of efforts to combat the state’s image problem (no thanks to Chris Christie). Oversize aphorisms fill the walls: “Jersey Strong is a mindset and an attitude that we can achieve anything we want. It’s not forgetting where you came from, the struggle we’ve overcome, and the future that we’re building.”

Several lifetimes ago, the place was an Acme super-market. It is massive, industrial, with pops of fluorescent green. Behind a glass door, an instructor shouts, “Fiyah hydrants!” to a cadre of women on all fours who lift their knees up and out in unison like male dogs aiming at the target.

On her treadmill, Dolores is shouting, “Defense! Defense!” I can hear her over my music. She’s effusive like that. Even her strawberry hair is full of pep. Our kids were on the same Little League team—the one coached by Bespoke Home Garage Guy. That’s how we met. She used to cheer loudly and high-five me when our boys were up at bat.

“OK, he did good, a walk is good,” Dolores would say, rip-ping off a piece of soft pretzel for me during the first game. Then, she would stick her fingers in her mouth and whistle, like the professional mommy sports fan she is.

Central Jersey folk are unabashedly open, even if, like Dolores and Jamie, they’re occasionally over-the-top. Dolores and her husband, John, adopted their son, Christopher, from Guatemala. John rigged up a batting cage in their backyard, and he and Dolores go to every one of Christopher’s practices, not to mention his games. And Jamie is always at school, volunteering, participating. People here seem at peace with themselves. Dolores and Jamie have strong accents they don’t try to curb—Jersey by way of Brooklyn (in Dolores’s case) and Staten Island (in Jamie’s), standard places of origin around these parts. People in this gym are clearly proud of their roots too. They are Jersey through and through, swigging from water bottles emblazoned with mascots from their children’s elementary schools, their calf tattoos of ’80s rock bands glistening with sweat.

Bruce Springsteen works out here. WoW/Acme/Jersey Strong costs $9.95 a month and Bruce Fucking Springsteen is a regular. I haven’t run into him, but at least three friends have sent me parking-lot selfies with the Boss. He fits right in at Jersey Strong, impossibly pumped, dedicated, and wear-ing a baseball cap pulled low like the other guys.

Perhaps it’s New Jersey that fits him. He has chosen to live in Monmouth County, where he grew up. Humility makes him true. Springsteen invented Central Jersey and the Jersey Shore in the cultural sense—rock and roll at its most blue-collar. So many people I knew growing up felt “born to run.” Being “sprung from cages on Highway 9” resonated. That was our road and our restlessness.

Outside the gym, people are texting and checking social media. The man who just bench-pressed 240 pounds is smoking a menthol cigarette. The locals of Central New Jersey do what they want. They don’t care what you think. And you never know if one of these souls, like Bruce, will translate New Jersey into art.