It is clear that if there is to be any revival of the utopian imagination in the near future, it cannot return to the old-style spatial utopias. New utopias would have to derive their form from the shifting and dissolving movement of society that is gradually replacing the fixed locations of life.

—Northrop Frye, “Varieties of Literary Utopias”

Nowadays we do not resist and overcome the great stream of things, but rather float upon it. We build now not citadels, but ships of state.

—H.G. Wells, A Modern Utopia

At the start of William Alexander Taylor’s 1901 utopian novel, Intermere, a small steamship runs into a fog bank three days north of the equator and drifts into a whirlpool. “I felt myself being dragged down to the immeasurable watery depths,” the hero recounts. He loses consciousness, and promptly wakes in a hammock on the curved deck of an entirely different kind of vessel—one with a “succession of suites and apartments, richly but artistically furnished.” The hero imagines for a moment that he is already in paradise, but the ship, a “merocar” propelled by “supernatural agencies,” turns out to be one of many technological advances engineered by a perfect society hidden inside the earth.

The jump from steam-powered transport to luxury yacht places Intermere midway along an evolution in utopian thought: A range of authors, architects, and engineers first identified paradise as a floating island, then as an island accessible by ship, and finally as the ship itself. Transport became destination.

In 2002, when the forty-three-thousand-gross-ton vessel the World shoved off from an Oslo wharf—christened by a triumvirate of Norwegian priests with a cocktail of holy water and champagne—it marked the first time it was possible to own real estate on board a ship.

The launch was greeted with telling fanfares.

“A global village at sea,” said the Boston Globe.

“Utopia afloat,” said Macleans.

*

I flew to Norway to meet the man who had coaxed utopian ships off the drawing board. Knut Kloster Jr. met me at the airport wearing a sea captain’s cap low on his brow so I could recognize him. It was odd to be met by Kloster himself. He was the father of the modern cruise industry, and the visionary scion of one of Norway’s oldest shipping families.

“I’m glad I don’t have to wear this hat anymore,” Kloster said.

On the drive into Oslo, he felt obliged to point out the city’s new high-speed train, and for the next couple of days he would sustain that act of reluctant tour guide. Kloster was almost eighty, but he was a large, buoyant, alert man, and he sluiced smartly through the streets, mumbling recriminations to drivers who didn’t quite grasp the system of signal-less intersections. We sat in the lobby of my hotel to begin our discussions. Almost all of my discussions with Kloster would be about what we would discuss in the event that we decided, collectively, that his was a story worth telling. I liked him immensely.

Kloster didn’t have a high regard for consistency, and even in our first chat he turned on a dime.

“Of course it’s an interesting story,” he said, of the grand megaship scheme he had first proposed in the 1970s. This wasn’t the World. It was a plan originally code-named the “Phoenix Project,” and over the years Kloster had spent tens of millions of dollars on it.

Then, in the very next moment, he said, “I’m a failure. I failed. You won’t get whatever you’re looking for from me. I’m not interested in cruise ships anymore.”

He took me to the only park in Oslo where he could walk his German shepherd off-leash, a sculpture garden filled with pieces by Gustav Vigeland. We climbed together to the centerpiece, Monolith Plateau, which featured a huge granite column of piled and twined bodies, people helping one another, straining against one another.

“It’s about life,” Kloster said. “Do you want to take a picture?”

I told him I didn’t have a camera.

“Good.” He was terribly relieved. “I thought you would want me to take pictures.”

Families and youths gathered around the statue, adding to the collage of forms.

“It’s about life,” Kloster said again.

*

Utopian literature is so full of ships and shipwrecks that no history of floating utopias would be complete without the story of a voyage.

My voyage began when a deliveryman ignored the threshold of my screen door and left a box in my foyer. I discovered the trespass with a little jolt of fear. Inside the box was another box, wrapped like a present with gold twine. Inside that was a leather document wallet stamped with a curious symbol. And inside that was my invitation to the World.

I met the boat in Luleå, Sweden, on the Gulf of Bothnia. The town was not exactly a tourist destination, and the only word my taxi driver needed by way of address was ship. At any given moment, the World might have a population of 200 guests and 250 crew members, giving it a unique passenger-to-staff ratio. Except there were no passengers, really. Apartments on the World ranged in price from $1 million to $8 million, and many of the residents used the ship as a second home—or third, or fourth. The World circled the globe endlessly, following world events and stopping at ports most cruise ships ignored. Like Luleå. Thus, it sometimes accepted humble moorings, and was now docked just up the coast from town, past some broken-down railroads and in line with a barnacly icebreaker named Twin Screws.

The taxi passed through the ship’s cyclone-fence checkpoint—manned by members of its Ghurka-recruited security force. I hurried up the gangway because it was raining.

A crowd of residents huddled inside, pressed together in the ship’s onboard security lock, waiting to disembark. I’d been told that privacy was the ship’s highest priority, but the residents looked friendly enough, bright and cheery, though not like tourists, and with a glow to them. The glow of knowing your time belonged to you.

*

Plato’s Atlantis, home to a “wonderful empire” that no man can visit for “ships and voyages were not as yet,” implies having floated on the surface of the ocean by sinking beneath it.

Callimachus the librarian describes Delos, birthplace of Apollo, as “a tiny island wandering over the seas.”

Lucian’s True History (circa 150 CE) satirizes a Greek tendency toward exaggeration, poking fun at Jason and the Argonauts. Its mock-epic sea voyage preludes with nymphomaniacal sirens and men using their erect penises for masts. The narrative takes off when a gust of wind lifts the ship to the moon. Back on Earth, the crew witnesses a battle among giants who sail about “on vast islands the way we do on our war galleys.”

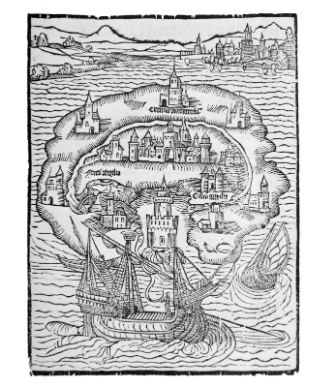

The archetypal island paradise became fixed in Sir Thomas More’s Utopia, which in 1516 gave birth to the entire utopian genre. You needed More’s narrator, Raphael Hythloday, a fool of a sea captain, to get to Utopia, but at least it stayed in one place. And so did maritime utopias, at least for a while. A couple centuries after More, utopian novels began to explore advances in naval technology, and the mobile, floating paradise was born anew.

While Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1626) looks to the distant past when the science of navigation “was greater than at this day” (think Noah), Tommaso Campanella’s The City of the Sun (1623) looks to the future, when vessels would move not with oars or wind but “by a marvelous contrivance.” After James Watt, inventor of the steam engine, proved Campanella right, it was utopian authors who anticipated ships that would become as much home as vehicle. Etienne Cabet’s Travels in Icaria (1839) describes a ferry that offers drawing rooms with fireplaces, and cabins outfitted with “all the… furnishings one might need,” and Theodor Herzl’s Jewish utopia, Old-New Land (1902), depicts the repopulation of the Promised Land via a vessel called Futuro that features an onboard orchestra and a daily newspaper. One delighted passenger never leaves, declaring, “This ship is Zion!”

In 1833, J. A. Etzler, a German inventor, proposed a fleet of huge propeller-powered landmasses closer to True History’s “war galleys” than Cabet’s or Herzl’s proto–luxury liners. Etzler un-got the joke of Lucian. The Paradise Within the Reach of All Men, Without Labor, by Powers of Nature and Machinery describes floating islands large enough for gardens and palaces, with room for “thousands of families,” and promises inhabitants the ability to “roam over the whole world… in all security, refinements of social life, comforts and luxury.” The islands could be built in a decade, he said, if only he found enough investors. He never did.

Six decades later, Jules Verne returned the idea to fiction with The Floating Island, a novel as cautionary as it is utopian. The book begins with the carriage of a French chamber quartet breaking down twenty miles north of San Diego. The hapless musicians wander onto a massive, docked “Floating Island” filled with millionaires, nouveau-riche robber barons who have shoved off to a different kind of life. The vessel is a perfect oval of five thousand acres, driven by hundreds of propellers and two dynamos that produce 10 million horsepower. Floating Island’s main town is Milliard City. The population is ten thousand, its army five hundred strong. The chamber group is contracted to offer performances for the mobile civilization, and for a time they are delighted. Yvernès, the first violin, anticipates that “the twentieth century would not end before the seas were ploughed by floating towns.”

Floating Island encounters various dangers—pirates, volcanoes, wild animals. Halfway through the book, the Floating Island Company Ltd. appoints a liquidator. “The Company had gone under”—pun intended. The millionaires produce the obvious solution: they buy the vessel themselves. Four hundred million dollars later, they’re back to island-hopping. But Verne will not permit utopia to last. In a clumsy deus ex machina, the unsinkable Floating Island begins to break apart, embodying tensions brewing between characters for hundreds of pages. The island snaps and sinks.

A century later, in 2002, French architect Jean-Philippe Zoppini un-got the joke of Verne. He proposed several designs based on The Floating Island. The shipyard that built the Queen Mary II agreed to construct the ship if anyone came along with the funds and infrastructure to operate it. None did.

*

On my second day in Norway, in the living room of his Oslo home, Kloster and I embarked again on discussions of the discussions of his story that we might eventually have.

The home reminded me of a Russian dacha: wide-open spaces, furniture from a range of centuries and cultures, original art on the walls that intimidated the viewer by looking a little familiar. Kloster was doubting himself again, and I found myself offering a pep talk to an earnest, broken utopian.

The Kloster shipping empire started with ice. Kloster’s grandfather hauled blocks by the shipload from northern Norway before refrigeration, and his father moved the business into oil when deposits were discovered in the North Sea. For a time the Kloster tanker fleet was as large as any in the world. Kloster studied naval architecture at M.I.T., and took over the family business at age thirty. He set the company on a new tack almost at once, constructing an almost nine-thousand-ton ship called the Sunward to ferry British retirees to Gibraltar. Kloster’s visionary streak poked through even then: the Sunward offered amenities unusual for a ferry—overnight cabins, onboard restaurants.

The Gibraltar plan snagged when Franco claimed the peninsula in a final power grab. As Britain and Spain waged a miniature cold war, Kloster was left with a ship but nowhere to sail it.

In Florida, future Carnival Cruise Line founder Ted Arison had precisely the opposite problem. He had built an infrastructure to fill a hole in the Caribbean cruise industry, but the Israeli vessel he had leased was recalled as a troop transport for the Six-Day War of 1967. He had a destination but no ship.

Arison rang up Kloster, and three weeks later the Sunward arrived in Miami.

The partnership was wildly successful—they added the Starward, the Skyward, and the Southward—but Norwegian Cruise Line (NCL) wound up in court. Kloster and Arison were different kinds of capitalists. Arison was ruthless, driven solely by profit and competition. Kloster wound up in tears on the deck of the Sunward, reading Charles Reich’s The Greening of America. Kloster held to capitalism like a faith, but tempered it with conscience and a belief that the cruise industry was uniquely positioned to battle back against cultural alienation and malaise, to become a medium for global communication.

The lawsuit ended with Arison retreating for the time being and Kloster moving to Florida to take over the business. In 1972, he envisioned a wholly new kind of ship. In an address titled “The Shape of Things to Come,” delivered to British travel agents in Vienna, Kloster quoted Emerson and laid out plans for a split-hull catamaran-style “ultramodern design” that would offer both an onboard observatory for astronomy and an underwater observation room for the study of marine life. The ship was no longer just a ship. Vessels of the future, Kloster told the agents, must serve as a “nexus” for three groups of people: those who visit them, those who live and work on them, and those who are visited by them.

In 1979, NCL was ready to move beyond words. The company bought the world’s last great ocean liner, the France, overhauling and rechristening it the Norway. This ship marked a paradigm shift. To that point, it was believed that twenty thousand tons was about as large as a cruise ship could get and still count on a profit. The Norway tripled that figure overnight—and it profited just fine. The ship featured a variety of shops and boutiques along “streets” called Champs-Elysées and Fifth Avenue.

Kloster hailed the “megaship” as “a destination in and of itself.”

Thirty years later, Kloster was the nice guy who had finished last. Arison had rebounded, using money that was rightfully Kloster’s to start what would eventually become the largest cruise company in the world. In the ’80s, Kloster bet everything he had on the Phoenix Project, his vision of a utopian city afloat—and lost.

*

In his living room, as I tried to convince him his story was worth telling, Kloster stared me down with a look that combined disbelief and corporate savvy.

He had an idea. He produced a small model of the underside of a boat, a tandem rudder system, and placed it on the coffee table between us.

“Say you are in a large ship. It is moving toward an island, some rocks. You need to turn—turn quickly.”

He explained that when ships reached a certain tonnage, single-rudder systems snapped from the pressure exerted on them. The solution was a second, much smaller rudder, positioned behind the first. This rudder was called a “trim tab.” The trim-tab turned the wrong way, shifting the current and creating a vacuum so that the larger rudder could turn the right way without breaking. Kloster demonstrated this with the model between his knees, moving the rudders back and forth and steering his hypothetical ship away from the rocks. The trim-tab rudder lent itself to metaphor—engineer Buckminster Fuller had been the first to suggest that it demonstrated “what one little man could do”—but sitting across from Kloster, I was baffled.

He stared at me. I asked for the toilet.

When I came out Kloster acted defeated and offhandedly showed me his home office. It was modest, a square meter beside the washroom—the office not of a mariner but of a submariner. The walls were jammed with bound collections of the correspondence that Kloster had conducted while attempting to bring the Phoenix Project to pass. The room was a dead child’s shrine. Kloster didn’t want to talk about it, but he wouldn’t throw it all away either. Now I understood. Kloster was the trim tab. He had turned himself the wrong way to steer us all clear of the rocks. It was the dilemma of all earnest utopians.

Kloster’s dilemma evolved in this way: After the cruise business had been born anew with the unholy matrimony of Kloster and Arison, Kloster charted the industry’s course with a kind of moral sextant for the next decade and a half. NCL bought an island and a few of its rivals. In 1984, the Norway was the largest cruise ship in the world, and the company dominated the business.

Then Kloster suggested an even wilder revolution.

Others had followed NCL’s lead in converting old ocean liners, but now there were none left. The only option for a revolutionary ship was to build one from scratch. Describing the initial planning of the Phoenix Project, Kloster said, “The design objective was to give passengers a sense of community.… We talked about a ‘downtown’ featuring broad streets and village squares, lined with shops, boutiques, and restaurants, nightclubs, cinemas.… In short, a city afloat.”

The Phoenix would exceed two hundred and fifty thousand gross tons, quadrupling the size of the Norway. Its aft split-hull would serve as a marina for four-day cruisers, each with the passenger capacity of the Sunward. Kloster announced “the dawn of a new age at sea,” and the plan came to include a number of smaller ships that, acting as remora to the Phoenix, would amount to a “global Chautauqua circuit.”

I gestured to the shrine.

“If there’s nothing here, then why are you keeping all these?”

“That’s a good question.” He shrugged. “There is a story here. Someday someone may want to know about it.”

*

Kloster had two sons, both of whom offered up innovative ideas for cruise ships. The older son, also named Knut, envisioned the World. The younger proposed a kind of floating beach resort. Like the father of prodigal twins, Kloster denied that either ship had anything to do with the Phoenix Project. To my mind, the World completed the story the elder Knut was reluctant to tell.

During the World’s first sail, the ship struck the same reef as Verne’s Floating Island. Its management company lost $100 million struggling through the climate of the post-9/11 travel industry. Its lender foreclosed, tried to run the ship on its own, and lost another $150 million. The future looked bleak until the residents stumbled onto the same solution as Verne’s millionaires: they bought it.

“The vessel is now a co-op,” said the San Francisco Chronicle.

*

I stepped onboard the World just in time to attend a crew recognition ceremony in the Colosseo, the ship’s theater. Almost the entire staff had gathered so that Captain Ola Harsheim, a man who looked exactly like a self-portrait of Van Gogh, could offer congratulations to various crew members on their years of service. The crew’s lodgings on the lower decks of the ship—the decks without verandas—made it easy to liken the World to a floating version of the phalansteries of utopian Charles Fourier, whose bourgeois vision retained class distinctions. E. M. Cioran had once described Fourier’s hotel-like phalansteries as “the most effective vomitive I know,” but nevertheless, a benign expression of “community” was on the lips of both residents and staff of the World for my entire stay. We’re all in the same boat, they said.

After the ceremony I was shown to my apartment. Mine was one of several spaces on board that had been compiled out of two studio apartments during a period of reorganization, and as my rooms were mirror images of each other the apartment had an odd doubling quality to it. I had two bathrooms, and two verandas with two sliding-glass doors. I had two flat-screen televisions, but only one kitchen, only one bottle of champagne waiting for me, and only one bathtub (double size). A number of strategically placed mirrors expanded the space and provided another source of doubling—or quadrupling—the result being that at one moment I could look through the pocket doors into one room and not be entirely certain that I was not already standing there, and at another moment glance into a chamber and experience a kind of vampire thrill at not seeing a reflection where I expected one. The apartment was a homey fun house, which was another way of saying that I sometimes got lost in it. It was one of the smallest spaces on board.

I stepped out onto one of my verandas just as a Swede, down by the dock, took a picture of the ship with me in it. In some ports, the World is a spectacle.

Lewis Mumford: “The autonomous machine, in its dual capacity as visible universal instrument and invisible object of collective worship, itself has become utopia.”

*

It took another French architect and the US military to make the Phoenix Project even conceivable.

“If we forget for a moment that a steamship is a machine for transport and look at it with a fresh eye,” wrote Le Corbusier in 1931, “we shall feel that we are facing an important manifestation of temerity, of discipline, of harmony, of a beauty that is calm, vital, and strong.” The son of a watchmaker, Le Corbusier was fond of saying a house was a machine to live in. In Towards a New Architecture, he argued that ocean liners already rivaled the world’s most impressive structures:

Le Corbusier went on to design buildings that looked like ships, and proposed apartment living with maid service, a kitchen staff, and a communal dining room like a luxury vessel. He insisted that “the steamship is the first stage in the realization of a world organized according to the new spirit.”

At about the same time, the US military was getting serious about bringing back the old floating-island idea. Edward R. Armstrong—once a circus strongman, later an engineer and inventor—proposed a battery of “seadromes,” floating airports that would enable fighter planes to hopscotch the Atlantic. The plan caught FDR’s eye, but advances in aircraft flight ranges made them obsolete. Another war-era plan was the top-secret Project Habakkuk, named for a biblical prophet (“Thou didst tread the sea with thy horses”—Habakkuk 3:15) and reportedly a favorite of Churchill’s. It was an artificial iceberg: a huge vessel made of “pykrete,” an ice-and-sawdust blend that rendered it impervious to torpedo strikes.

Habakkuk never came to pass either. But the floating-island concept would never fade from the military imagination. After the seadrome, the basic concept underwent periodic revision: the “megafloat” and the “Mobile Offshore Base.” In 1996, plans were drawn for the “Joint Mobile Offshore Base,” a multi-module platform like a floating Guantánamo, featuring an artificial beach for hovercraft, space for a POW camp, and room for 3,500 vehicles, 150 aircraft, and 3,000 troops. It was Lucian’s “war galley” with airports and Quonset huts:

*

I was given a tour of the public areas of the World, what in ship parlance was called “the Village.” The main hallway through the Village was “the Street,” and along it were the theater, a small sanctuary space, a (very) high-end jewelry store, an equally impressive boutique, a deli for gourmet foods or simple groceries, a cigar lounge, a small casino, an Internet café, a four-thousand-volume library, a handful of restaurants, a couple of bars, and a spa that sported quasi-spiritual massage facilities and a state-of-the-art gym. The World had been criticized as something of a ghost ship, and it was true that a lot of the time it didn’t seem like there were many folks around: the shops and the casino never opened while I was on board. But the residents argued that if others wanted a lot of cruise zaniness, late-night parties, and lines for dinner, they were welcome to it. It was not for them. Their apartments were not staterooms where they slept while on vacation. They were homes.

I was shown what a couple of the larger homes looked like. The first was a larger, grander version of my own apartment, a space that was for rent while the owner was not on board. It went for thousands per night. The second would have suited Captain Nemo. Each of the three bedrooms had its own bathroom. The whole place was paneled. The master bedroom had its own veranda and what my guide called “a religious experience of a closet.” The residents spent a good deal of time customizing their spaces, and the upper-tier staff said they’d been surprised at how unique the apartments could be made to look, transformed and modified, sometimes with furnishings, sometimes with art worth more than the apartment itself.

I met no one who had seen every space on board.

I had dinner that night with James St. John, former president and CEO of ResidenSea, the resident-owned company that managed the World. We ate at East, the ship’s generic Asian restaurant. The ship actually had too many restaurants—they opened on a rotating schedule—but East was a favorite. Most of the restaurants offered outdoor eating when weather permitted; the annual food budget was in the millions. Later, I stopped by the Colosseo to see a local combo (sax, bongos, harp, accordion, xylophone) rush through a variety of show tunes so they could disembark before the ship left Sweden. I met an older couple walking through the Village after the show. They liked the performance, they said, but they were fonder of the ship’s lecture series. Wherever the World went, it was accompanied by a team of scholar–tour guides who gave talks that put the region into historical context. The ship was now in the middle of its “Bothnian Expedition.”

“You kind of schedule your day around it,” the woman said.

It was their second time on board; they were thinking of buying an apartment. They were renters, but came for stays of around six to eight weeks. I converted weeks to dollars.

“That’s a good chunk of—time.”

“It is,” the man said. “And now it’s time to go to sleep.”

I wandered the Village. The cigar lounge was empty; the chess tables in the game room had no pieces. The World was less like a ghost ship, I thought, than an amusement park you’d leased. Or bought. At an empty bar on Deck Eleven, I chatted with a Filipino barman. He somehow knew my name. He’d been on the ship since the beginning, and had traveled around the world several times as a result. An hour after the engines grumbled to life, he looked out the window and became excited.

“Mr. Hallman—we’re moving!”

We stepped out to the rail to watch the land slink by, passing steel foundries on the edge of Luleå, their towers topped by a blue and spectral fire, the negative signature of heat. Below us, the Gulf of Bothnia was a dark winter’s sea, choppy and pleated in moonlight, like skin viewed through a microscope.

“This may be the last time I see Sweden,” I said.

“Really.” There was a touch of pity in the barman’s voice.

*

It was Fuller—of trim-tab fame—who was the first to marry Le Corbusier’s maritime idealism to something that actually had a chance to hit the water. Early in the 1960s, a Japanese patron commissioned Fuller to create a “tetrahedronal floating city” for Tokyo Bay. Fuller designed three floating cities, one for harbors, one for semiprotected waters, and one for deep sea. In Utopia or Oblivion, Fuller cited a claim that visions for perfect worlds failed because they were unrealistic from the get-go. Ship design, however, offered hope, as it required a different sort of design discipline. All of a ship’s functions had to be comprehensively understood in advance. If you were unrealistic, you sank.

Fuller’s patron died in 1966, which cleared the way for the US Department of Housing and Urban Development to get interested. HUD passed the tetrahedronal city on to the navy, which deemed it both water worthy and economically feasible. Baltimore, Maryland, remained interested in a city for the Chesapeake Bay until LBJ, also a fan of the plan, left office. Johnson took two of Fuller’s models to his presidential library in Texas. They’re still there.

*

The strange symbol on my document wallet—the symbol of the World—was not a picture of a ship. It was a picture of an island.

The original frontispiece of More’s Utopia featured not just one island but two. It’s generally held that the shape of Utopia—a crescent whose points almost touch, making for a large inner harbor—comes from Plato’s description of Atlantis. Plato, it’s been suggested, may have been thinking of the Greek island of Santorini, which is crescent shaped and has smaller islands situated between its points. This suggested to Plato a tactically perfect location to erect a fortress that would make one’s inner harbor impenetrable.

Utopia, however, did not start out as an island. It was a peninsula when the land was first conquered by King Utopus. Utopus dredged the narrow band of earth connecting it to the mainland, snipping its figurative umbilicus and delivering the infant of a better world. That Utopia was now suspiciously womb shaped nodded both to Hesiod’s Elysium (circa 700 BCE), whose “islands of the blessed” were swaddled in the ocean’s amniotic fluid, and to first-century gnostic mystic Simon Magus, whose Eden was comfortably in utero. More hyperextended the metaphor. An inner harbor guarded by a jutting phallic tower made the book jacket of Utopia a rather clinical depiction of coitus.

I would sail with the World from Luleå to Vaasa, Finland, and then down the Finnish coast to Mariehamn in the Åland Islands, a curious archipelago in the mouth of the gulf. The islands technically belonged to Finland, but the population spoke Swedish and they were recognized by the United Nations as autonomous. The tactically advantageous location of the Ålands had long been known, though it wasn’t until centuries after More that anyone tried to build a fortress there—first the Swedes, then the Russians. Nevertheless, it seemed perfectly reasonable to wonder whether More, in designing Utopia in Antwerp (far closer to Finland than Greece), might not have been thinking of Bothnia rather than Plato.

*

I woke at five a.m. to a peach-colored world, the chill blue water stripping by at seventeen knots, a warm wind puffing my curtains, and a sound like light surf rising from the waterline. From the bathtub’s window I watched the first spark of sun ignite the horizon, and room service brought a light breakfast. The ship had encountered gale-force winds and four-meter waves overnight, but the captain had deployed the stabilizers, the ship’s ten-meter wings, and we barely felt the heavy seas. From that point on in my voyage, as though the secret sharer of my subconscious recognized the feel of warm, moist containment and the possibility of months-long rest, I would be torn between trying to see the ship and just coming back to my apartment, my home, to survey the gulf. It was a womb with a view.

After breakfast I went back to sleep on the spot where sunlight had warmed the bed.

The ship had arranged a Thai lemongrass-oil massage for late morning, and my masseuse apologized for the lack of candles and incense (ship regulations) before she went to work (“Mr. Hallman, put your face in the hole, please, sir”). I met St. John for lunch and then had a tour of the back of the house. He was jolly, something like the Skipper from Gilligan’s Island. St. John had once considered the seminary, but life had tacked, and time in the military, in the hotel business, in the shipping business, and finally as the manager of a private community on Jupiter Island, Florida, left him with the perfect résumé for the World.

As we climbed downstairs, St. John insisted the World was the cleanest ship in the industry. As above, the main hallway in the back of the house was a “street.” It was utilitarian but tidy. There were two below-deck saloons, an officers’ club, and a crew bar, but in keeping with the lean-toward-egalitarian theme of the ship, staff, officers, and crew mixed freely. We visited the mooring decks as a team of men were tying us off to the dock in Vaasa with cleats the size of anvils and capstans the size of barrels. We visited the recycling facility. Ecological progressiveness was one of the few traits common among the residents, St. John said, and the ship, in addition to being the first vessel of its class to run on industrial diesel instead of heavy bunker fuel, took pains to recover as much of its waste as it could. Everything not crushed and stored for recycling was incinerated—including sewage.

“We even capture our ash,” St. John said.

The residents’ routine was morning exercise in the pools, or a walk on the track or on treadmills in the gym, and a leisurely breakfast as the ship pulled into port. Some vacated their apartments early so that the crew could get their work out of the way and go ashore for the day. The residents did the same, either renting cars for private excursions or signing up for prearranged tours that were announced in several onboard publications and on the ship’s morning TV news show. I didn’t disembark for a day or two. I played Pebble Beach on the ship’s high-tech golf simulator, I lunched with the captain, and I got a peek at the cargo-van-size engines and the onboard water treatment facility that could produce three times the two hundred tons of fresh water the ship used daily.

I went to a lecture about the Åland Islands. The archipelago sat right on an ancient line between hunter-gatherer and agrarian civilization, and the lecturer offered us his theory on how the Ålands’ aborigines, who butchered people and seals alike and buried them all in the same mound graveyards, eventually became cultural Swedes but Finnish nationals. The Gulf of Bothnia was curious not just for the Ålands, he said, but for the fact that it was all becoming slowly shallower.

The islands were moving—up.

*

The Phoenix pitted Kloster against his family. The strain began when NCL took off; the Phoenix was simply too risky. Kloster stepped down from the chairmanship in 1986, divesting himself entirely, taking only the plan with him. He turned his full attention to bringing the Phoenix to pass. A team formed around the effort, and came to include administrators of maritime organizations, two former admirals, and a former commandant of the Coast Guard. Various retrofits of the blueprint saw the ship renamed Phoenix World City and America World City. When it turned out that the vision future-shocked everyone it touched, the America World City marketing team turned to the imagery of Le Corbusier to sell it (see image on facing page).

It didn’t work. America World City came closest to being built in 1989, but Citicorp pulled out at the meeting that would close the deal. Kloster suspected Arison was involved. In 1996, Westin Hotels and Resorts backed the project, but the ship’s in-house champion was ousted in a squabble over personalities. The project stalled there.

At about the same time, Kloster’s son’s vision was just hitting the drawing board. The World suffered through five years of downsizing before construction began.

“This is the new lifestyle,” the younger Knut said when the World finally got wet. “To travel the world without leaving home.”

*

On my last day on board, I was invited along with forty or so residents to visit a few sites of interest in the Ålands. We assembled in the Village, filed down the gangway, piled onto a chartered bus. The residents were millionaires to a man, but as we pulled away they chattered and laughed like kids riding home from school.

“They’re affluent people, but warm,” I’d been told, the caveat added as though it ran contrary to expectation.

Which made me wonder whether the World, beyond allowing you to stay at home while you traveled, offered the possibility of community, of kinship, to those whose success tended to alienate them. It may be wasted compassion to empathize with the wealthy, but it seemed to me that the wealthy remained apart not because they liked being apart, but because an economic system that encouraged class division—a system in which not everyone was in the same boat—chopped people into insoluble bits: wealthy and poor, cold and warm. Dichotomies. Did utopia have to eliminate class? Could a class system figure out how to retain dignity for all involved—without inducing vomiting? Was Fourier right to imagine perfection without aspiring to economic equality? Was that the best possible world? The World was born of capitalism, but it seemed to me that it took at least one step toward transcending it. It wasn’t just the community on board, the resident poker games that sprouted up spontaneously or the karaoke nights that revealed the wealthy had the same plebian tastes as everyone else. It was, too, a conspicuous lack of currency—of transactions—on board; it was the green values they embraced, not because it was profitable, but because they thought it right; it was the government they had formed themselves, intentionally, when they bought the ship.

“By the way,” St. John told me, “I don’t think it’s utopia.” I wasn’t so sure.

Among the sights we were on our way to see in Mariehamn were the fortresses that had tried to take the tactical advantage of the Ålands that More and Plato prescribed. The Swedish castle stood boxy and tall, but it had failed to fend off the Russians, who had moved in and begun their own construction. The Russian fort was only half complete when ten thousand Frenchmen and forty British ships under Admiral Nelson attacked and brought it to the ground. It was another of the World’s lecturers—Noel Broadbent, an archaeologist with the Smithsonian—who told us this story as we stood before the ruins of one of the fortress’s walls. The residents wandered, petting the cold, thick cannon still in place and admiring the impact marks of the British ball.

We went home to the ship.

I left the following morning, taking the same plane out of Mariehamn as Broadbent. We chatted in the tiny airport. I likened the World to a votive ship we had seen in a church on our tour the day before. Common in Scandinavia, the model ships hanging from church ceilings symbolized the spiritual journey of the early Christian community. Broadbent nodded, but thought the World was closer to something from the work of Swedish poet Harry Martinson, who had mulled real-life merchant-marine experiences in books of poems called Ghost Ship and Trade Wind. Then Martinson shared the 1974 Nobel Prize in Literature for an epic poem called Aniara: A Review of Man in Time and Space, which imagined huge space vessels called Goldondas ferrying émigrés from a polluted Earth to a better Mars.

“It’s an interesting concept,” Broadbent said, when we’d taken our seats in the island-hopper to Stockholm. “If you’re self-contained—if you can do it on your own—then you’re almost like those sci-fi stories of ships carrying civilization off after cataclysm. It’s not far from that. And islands are not so different. They’re moving, too—in geologic time. Either way, it’s all about boundaries and travel.”

As the plane banked up, we had a view of the World at its mooring, as large as the city beside it but small as a toy from our vantage.

*

“I was depressed all yesterday,” Kloster told me on my last day in Norway.

I wasn’t supposed to see him at all—his German shepherd had fallen ill and needed to go to the vet—but then the plan changed. When we met in the lobby, Kloster was sad not because of the dog, but again because he thought his story was uninteresting.

We drove down to Oslo’s fjord. Several cruise ships were docked monolithically alongside the city. Kloster’s walrus-like benevolence gave him the naive serenity of a mystic. He pretended not to notice a prostitute streetwalking the pier.

We visited a series of maritime museums together. The first was dedicated to Thor Hyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki expedition. If Hyerdahl’s ocean crossing on a balsawood raft dabbled usefully with the past, I thought, then Kloster’s imaginary megaship had tinkered with the future. The second was devoted to unearthed Viking ships. I climbed a parapet to look down into the ancient wooden hulls, then glanced back at Kloster in the middle of a hallway, tourists streaming around him as though he were an atoll. The last museum was a tribute to Norway’s shipping business, a gallery of models and to-scale mock-ups of tiny crew quarters. We walked directly to the back of the museum and found the original miniature of the Sunward, set without fanfare among notable old tankers.

After Kloster left NCL, the company abandoned his guiding principles, his “process of vision.” It sailed into a whirlpool of bad luck and bad publicity. It reflagged its vessels in the Bahamas, dumped agreements that protected third-world staff, and tried to go public in 1987 only to have its IPO fall on the day after Black Monday. In the ’90s, it tried to reverse course with a more aggressive approach, but was already taking on water. Eventually even Arison joined in the bidding when the company was put on the auction block.

After the final deal to realize America World City petered out, Kloster became a different kind of utopian, proposing smaller projects that were even bigger long shots. In 2001, he suggested a seventy-story glass globe for the World Trade Center memorial, called “Planet Earth at Ground Zero.” A year later he wrote to then Secretary General of the United Nations Kofi Annan proposing Gaiaship, a goodwill vessel that could be paid for, he suggested, if all the countries of the world contributed one tenth of one percent of their military budgets.

Arthur C. Clarke wrote a letter of support—he called ocean liners “a microcosm of the Earth”—but an aide to Annan rejected the proposal.

In the meantime, Kloster’s original vision kept creeping toward reality.

After the Norway, cruise ships started getting bigger. A number of ships in the ’80s came in at around 40,000 tons, and in 1988 the Sovereign of the Seas upped the ante to 73,000 tons. Carnival broke 100,000 tons in 1996, only to be eclipsed two years later by the Grand Princess at 109,000 tons. More followed—142,000; 151,000; 160,000. Recently, Royal Caribbean proposed the Genesis Project, a 220,000-ton vessel scheduled to sail in 2010. Similarly, the World can spot competitors in dry dock: Residential Cruise Line plans a luxury ship called Magellan; Ocean International Holdings Ltd. has promised a similar vessel, the Four Seasons; and Condo Cruise Lines International claims 90 percent sales on a plan to convert old cruise ships to condominiums.

“The luxury of new views every day,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch said of the last of these.

At the shipping museum, Kloster and I came around to the model of the Norway. Kloster showed me how the Norway differed from newer monstrosities: it was small enough that its hull was curved all the way around. More recent ships were boxier, their cross-sections interchangeable. Each section of the Norway was unique.

“It was a good ship,” Kloster said, as though speaking over the remains of a man in state, one who had lived long and perhaps made a difference. Kloster went a bit woozy looking through the model’s glass case. The Norway had had a tough run. In 2001, it sprouted dozens of leaks in its sprinkler system, incurring fines, and two years later an explosion in its boiler room killed eight. It was decommissioned not long after.

I asked Kloster where it was now. He said he’d heard it was lying on a beach in India, but he wasn’t sure.

“It’s OK.” His lips formed a smile for the first time all day. “A ship can’t last forever.”