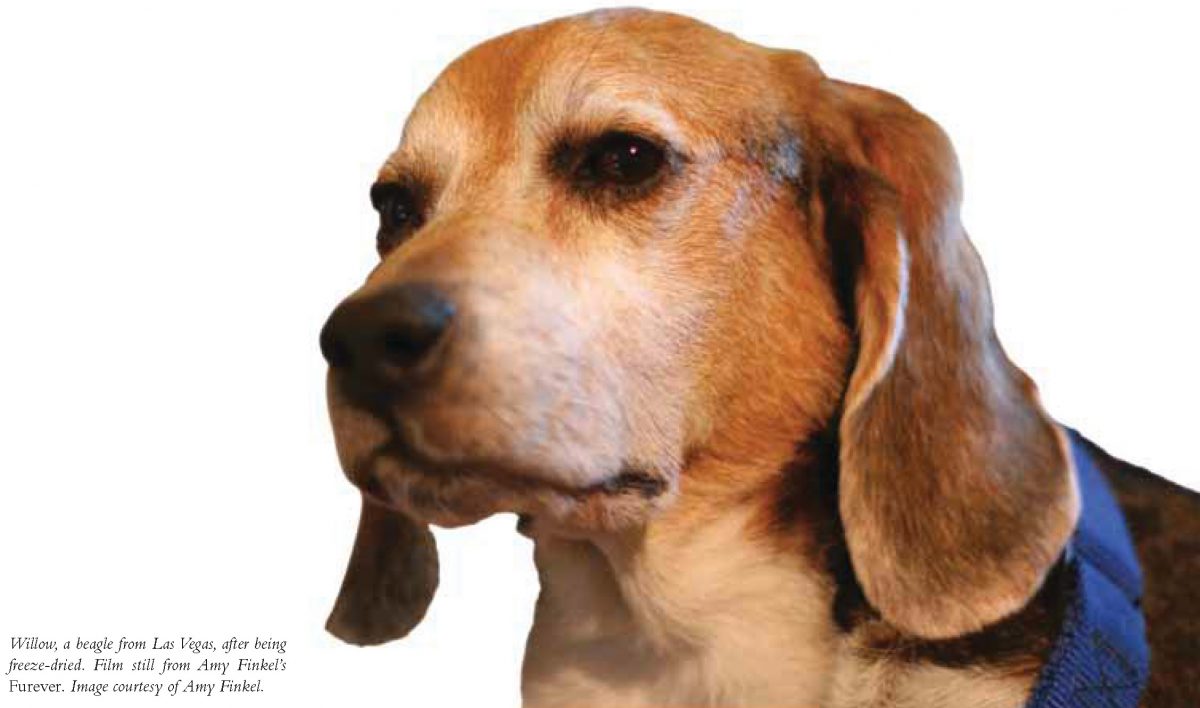

This issue features a microinterview with Amy Finkel, conducted by Molly Oswaks. Finkel’s first documentary film—Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart: The Banjomaniacs of Guthrie—was nominated in 2004 by the International Documentary Association for the prestigious Pare Lorentz Award. Her newest project, Furever, is an exploration of pet preservation, the processes by which a deceased pet is professionally conserved. Through expert interviews with grief counselors, pet preservationists of all sorts, and grieving pet owners, Finkel aims to open up a new perspective on grief, death, and mourning.

–Molly Oswaks

PART I

THE BELIEVER: How difficult was it for people to relive these very devastating pet-death experiences with a camera and mic shoved in their face?

AMY FINKEL: First of all, I don’t know if it’s the freckles, but I look young, so people trust me––as they should; I’m a thinking, feeling individual, and can totally sympathize with everything they’re going through. Half of the interview footage is people just bawling through basically the entire thing, then they would stop, then occasionally I would cry with them.

There is so much emotion coming from these people. It was tough. I’m not trying to sensationalize. If someone asked me to stop, I did. It didn’t feel like a reality-TV set in any way. It felt like reality.

BLVR: What are some of the weirder things you’ve come across in your research?

AF: Someone had a dog who’d just had his leg amputated. He wanted the leg preserved. The dog was fine, but he wanted the leg. That, to me, is creepy. That goes to a very different level, and I have a tough time understanding it.

PART II

THE BELIEVER: Is there anything you’ve come across that seems dangerous or destructive?

AMY FINKEL: You can’t fault someone for loving their pet too much. But sometimes people so do not want to let go of their pet—they are so attached that they let their pet suffer at the end. It’s upsetting. Like, they let their dog live two weeks longer than it should. People like to hold off death as long as they possibly can. Hopefully preservation will make it so that people are less terrified, and they can euthanize on a quicker basis, and then get their pet back sooner.

I remember one experience. My rat had passed away––I think in Seattle rats have a better reputation than they do in New York. They’re very smart; she was cage-trained. I would come home from high school and she would sit on my shoulder for five hours sometimes. So we became very close. And of course, we project onto these pets, we anthropomorphize them, which I find endlessly fascinating as well. So we became close friends. And she passed away, and my parents were not home from work yet, and I remember being just devastated––and with small animals, rigor mortis sets in quite quickly, so here was this hardened, dead rat, and I’m holding on to it for probably an hour or two before my parents got home and pried her out of my hand… I didn’t want to let go yet.

There’s a little bit of a disconnect, sometimes, with my subjects, where they think that their preserved pet is still living. But beyond that, if preservation offers comfort, what’s the big deal?

PART III

THE BELIEVER: You’ve received a lot of positive early attention for your film. I’m curious whether PETA has had anything to say.

AMY FINKEL: There’s been a lot of negative press, not about me as filmmaker, but rather about the effect of preservation on the pet. But the pet is dead—it doesn’t know what’s happening. From an ethical standpoint, there’s absolutely no difference between what these people are doing and what happens to humans when they die. Cremation? I mean, that’s brutal. Embalming, autopsies––there’s nothing pretty about that situation. So what’s the big deal with pet preservation? Does it hurt society in some way?

PART IV

THE BELIEVER: Why make a documentary film about all the weird ways people preserve their dead house pets? It’s a pretty strange subject.

AMY FINKEL: I’ve always been a pet lover, and my parents were really cool about it; we would adopt rats and geckos and parakeets and dogs. I had friends, but for some reason I became so attached to my pets, and letting them go was almost the most brutal thing I’ve ever had to go through––almost more so than with humans. So I really empathize with my subjects that way.

You know, a lot of people think the people I filmed are kind of crazy––and they are kooky, and maybe there’s something a little odd about them, but for me the sociological implications are what interest me. Human bonds, family bonds, are sort of atrophying, so people are moving further away from one another. People are having more pets now instead of children. What does it mean that these pets, who are replacing children in our lives, have a lifespan of ten to twenty years? Now we live in this society where we can get anything we want, anytime we want. Given the new technology that’s available to us, do we need to let go? That these people can keep on looking at their pet… to me, it would offer no comfort to have my pet on a mantel, knowing that the pet is dead. But to them, the pet is not gone. A lot of the women I filmed are very religious. It’s interesting to see them wrestling with the concept of “Will I be reunited with my pet in heaven?” When I was growing up, there was none of that. When the pet is gone, they’re gone. You’ll never see your pet again. We buried our small pets in the backyard.

BLVR: How many pets are in that backyard cemetery?

AF: Oh, god! Well, we were not great with birds, and when you’re adopting a rat after it’s been alive for a year… they only have a lifespan of one to two years. I would say ten to twenty creatures. We had a lot of pets.

PART V

THE BELIEVER: Have any of these people gone on to get new pets, in addition to their freeze-dried pets?

AMY FINKEL: They have, and watching how their pets interact with the freeze-dried pets is interesting. They’re especially curious about it, usually for a couple of months. Then it just becomes part of the furniture. It also depends where people keep their pets. I interviewed a woman, she was twenty-six years old, and what it came down to was that she simply did not want to bury her pet. She was from rural Pennsylvania, and she said, “I don’t know where my husband and I might move to in the future, and I want Yogi to be with me for eternity. I don’t want him to be buried in this home, because what if we move homes?” That was a story I heard quite frequently. So she keeps Yogi in a box in her closet. It’s like a mobile burying unit. Brenda, who was interviewed with her grand-daughter—she really felt that she was cheating death by freeze-drying her cat. She really felt her pet was still “around,” essentially. She talked about sleeping with the pet in the future. She said, “I understand that Tiff will be hard, and she won’t move with me in the way that she used to, but it offers me comfort to do this.”

PART VI

AMY FINKEL: I’m interested in the psychology of people who preserve pets. I have pet-bereavement specialists, ritual specialists, people talking on religion. Beyond that, it’s about the specific pet-preservation techniques and what they mean. There’s pet mummification, and pet-ash tattooing, where people tattoo the ashes of their pets into their bodies. LifeGems: people make diamonds out of the carbon remains of their pets. I touch on cloning. Pet bequests: people give millions of dollars to their pets when they die. Vinyl records: people record their pets’ sounds on vinyl, and then a company in London puts the ashes of those pets into the vinyl, so you have a record pressed with the ashes inside it. Taxidermy, which encompasses a number of different ways to preserve an animal. The reason people don’t taxidermy pets very frequently is because it’s very expensive. The freeze-drying process essentially is: They take the pet, they take the internal organs out, clean it, dry it, stuff it with straw and wires. When your pet dies, you have to put it in the freezer immediately. Then when you take it out of the freezer, the rigor mortis is gone. Freezing removes it.