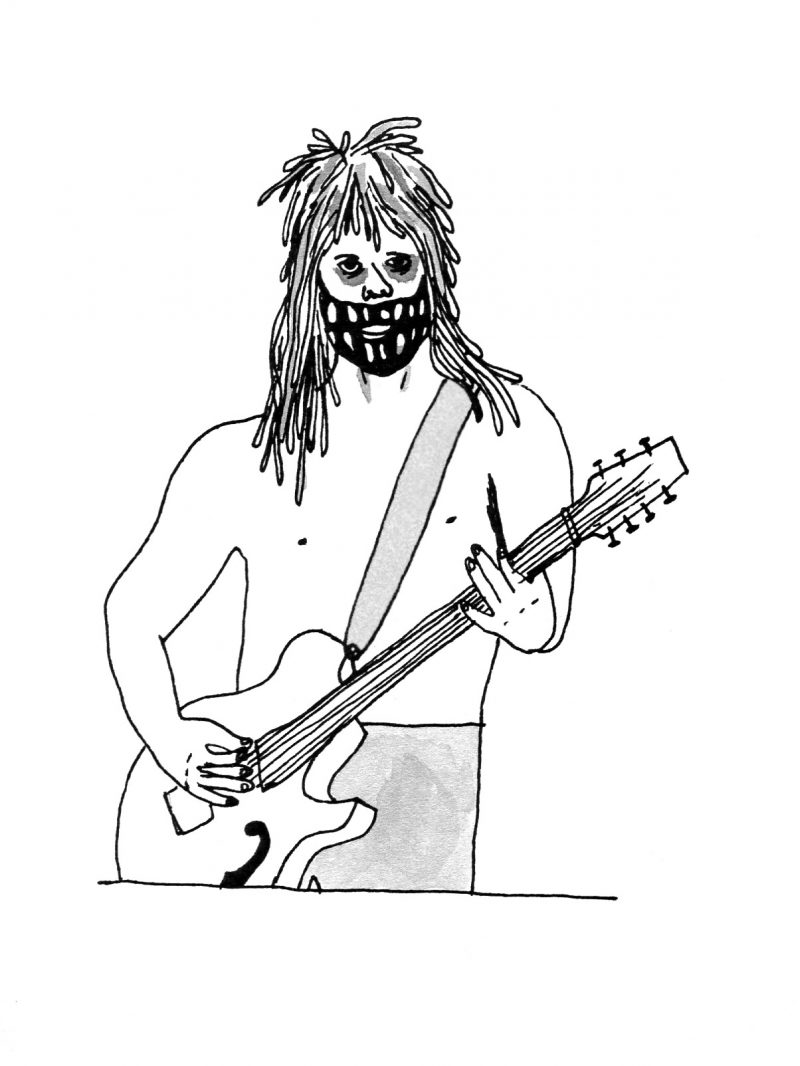

This issue features a microinterview with Wes Borland, the longtime guitar player for Limp Bizkit, a rap-rock group that came to success in 1997 while touring in support of their debut album, Three Dollar Bill, Yall$. Wes was at the band’s core, yet he was unlike the other members. Onstage, he emerged with his bandmates from a giant toilet bowl, wearing heavy makeup, black contact lenses, and sometimes a bunny suit without the head. He carried a strange lawn ornament that he placed atop his amp before plugging in his guitar, a seven-stringed marlin-looking thing on which he could produce both electric and acoustic sounds. “There’re a lot of dynamics in our songs,” explained the then-twenty-two-year-old, “so this guitar is a broader tool.” Over the next decade, Borland would quit and rejoin Limp three times, take up keyboards and cello, and sing for Black Light Burns, whose new album debuts this fall. This interview took place while Borland was in Florida visiting his parents.

—Cole Louison

PART I

THE BELIEVER: Did you always dress up onstage?

WES BORLAND: Yes. I went to an arts high school, and had always been interested in sculpture and painting and drawing. Guitar kind of became a hobby of mine, and I had seen David Bowie and Kiss and Alice Cooper and Marilyn Manson—even GWAR—and so when I started playing in garage bands I started doing little things onstage that were nothing more than a mask or minor makeup, because the stage seemed like such an opportunity to do something outrageous. And it kept growing and growing and growing. When Limp got signed, that changed my aspirations from being in fine art. Being a musician was the job I didn’t expect, and I ended up going, “How can I incorporate this?”

BLVR: By the time we saw you on MTV, you had incorporated it. The makeup was not minor.

WB: Well, I was bored. There’s so much downtime on tour. I ended up going around and finding thrift stores and costume shops in towns, spending whatever per diem or money I had on makeup and lipstick, and I started putting outfits together. And as the band gained more success—like, suddenly I didn’t have to carry anything or tune my guitars—I had more resources for stage outfits, and I started thinking about the show all the time.

PART II

THE BELIEVER: On TV you seem to have two personas. The polite, uncomfortable guy on camera feels different than the bunny monster, whose energy is both very aggressive and very engaged.

WES BORLAND: It’s what allows me to have that power. And I’ve noticed that the more elaborate the costumes got over the years, the more they developed into characters, the more I felt like someone else. It’s like pulling on a shirt, but having the Superman symbol underneath. There is also a very different character I have in Black Light Burns, my other band. I grow my hair and mustache out, and wax the mustache and then paint it on even bigger. I’ll wear period clothing that looks like Bill the Butcher. But in that band I’m the singer, so I don’t wear any contact lenses, because I feel that takes the audience away from me. When my eyes are dead and black-looking, I lose a connection with people who are looking at the singer to connect with the band, so I won’t do that.

PART III

THE BELIEVER: How did your bandmates feel about playing hard rock/ rap with someone dressed like a vanilla gorilla?

WES BORLAND: At first I tried to get the other guys to dress up, too, but they didn’t want to do it, so that sort of became the thing in Limp Bizkit—you’ve got a bunch of guys who look like normal dudes, and then one guy who dresses like a space alien or a zombie. But soon I started getting into

more-serious art and artists, then started going to the opera. I went to The Damnation of Faust that the L.A. Opera put on, like, eight years ago, and was just thrilled by the costumes. So I started researching opera-costume makers and stage makeup, and it just built and built.

BLVR: You’ve left the band twice, citing artistic differences, yet over the years your playing and performance have intensified. It seems like you’ve turned everything up instead of down to try and fit in more.

WB: Yeah, exactly. When I was out of Limp I was briefly in Marilyn Manson. And that was a different experience, because nothing I did onstage was ever going to top what anyone else was doing. There was a different feeling playing those shows. It made the theatrics and costumes not seem as extreme, when everyone on-stage was so dressed up. It all just looked like we were in uniform.

PART IV

THE BELIEVER: There’s a recent YouTube slideshow of your stage costumes, where each costume has a name, as if they’re personalities. Someone else did it, but I wondered if costumes ever develop into personas, like a cast of characters?

WES BORLAND: Performing, I never want anyone to think this or think that. None of the characters have names. Usually, making them up, I’ll just be into different artists. Like last year a lot of costumes were Matthew Barney–esque. In Drawing Restraint 7 there’s a couple of satyrs that are driving around Manhattan in a white stretch cocaine limousine. They’re wrestling in one part, and they kind of look like goats. And that was an instant thing where I went, I want to have something that looks like a goat. I want to be real fleshy and pinky and the opposite of what a scary heavy-metal creature would look like. This year I’m into Eiko Ishioka. She did all the costumes in The Cell and The Fall [and Bram Stoker’s Dracula, for which she won an Academy Award]. Her costumes are totally insane.

PART V

THE BELIEVER: Your costumes never seem to connote just one thing, like one thing that’s scary, one thing that’s ironic. What comes to mind right now is the Technicolor lounge-singer phantom who’s not wearing any pants.

WES BORLAND: Oh, yeah! The prom outfit. The hair for that is made of feathers. But all the characters come from what effect I want to put out. That’s the main thing: everything onstage has to make me feel, in some way, tapped into this little-boy thing, where I want to be a superhero or I want to be a warrior. I want to be filled with all this energy that comes from tricking myself into thinking that I’m more powerful than I am, or have more confidence than I would be capable of in normal clothes. It’s just becoming a monster in some way, and that helps me go out in front of ten thousand people and act like I own the place.