A Review of The Hashish Films of Customs Officer Henri Rousseau and Tatyana Joukof Shuffles the Cards (a Novel Against Psicho-Analise)

Daniel Elkind

According to writer and translator W. C. Bamberger, around 1912 the poet Blaise Cendrars “started a small press, Éditions des Hommes Nouveaux with the help of an anarchist who owned a clandestine printing press at the Mouzaïa Quarter, 19th arrondissement.” That anarchist was Emil Szittya, the pseudonym of the writer, critic, and painter Adolf Schenck, whose legacy has largely remained in Cendrars’s shadow ever since. His biography bears the telltale marks of a bygone Europe: born to a Jewish family in Budapest, he died in Paris in 1964, having traveled everywhere in between to witness the death of the old order and the birth of a modern, cosmopolitan Europe—as bewildering and miraculous as it was stimulating—a world in which the work of a Jew from Hungary could be “gaped at in the Louvre by tall, thin Englishwomen.” On the other hand, Zurich, where Szittya befriended the Dadaists Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings, was to him forever “a city that smelled of cheese…”

Perhaps best remembered today for his gossipy 1923 book Kuriositäten-Kabinett (Curio cabinet), in 1925 Szittya wrote, with Selbstmörder, one of the first histories of suicide. A polyglot vagabond like his friend Cendrars, he knew just about everyone worth knowing, and often embellished the truth, claiming to have written books that have since been lost or that never existed—though his fellow hashish enthusiast Walter Benjamin does attest to a missing edition of an early work, Ecce-Homo-Ulk, in his essay “Books by the Mentally Ill: From My Collection.”

Published in German in 1915—and this year in English by Wakefield Press—The Hashish Films of Customs Officer Henri Rousseau and Tatyana Joukof Shuffles the Cards (A Novel Against Psicho-Analise) is Szittya’s first extant book. Mixing phenomenological descriptions of mental states and impressions with psychedelic images, it testifies to the narrator’s dedication to hallucinations via hashish and opium. As the subtitle implies, Szittya took aim not only at the period’s fashionable psychoanalysis but also at traditional narrative itself: his outsize avant-garde ambitions established a now-familiar relationship between linguistic obscurity and literary marginality. (It is no coincidence that assassin and hashish are etymologically related.) According to art historian Magdolna Gucsa, friends and colleagues such as Hugo Ball referred to him variously as “the knight enshrouded in fog, the pariah dog, the oddball, the satyr or the holy seraph.” The narrator’s confessions can often apply to the author just as well: “Now I cavort with visions. I have never made concessions to life. It is lovely to be in disguise and to dare to confide in no one.”

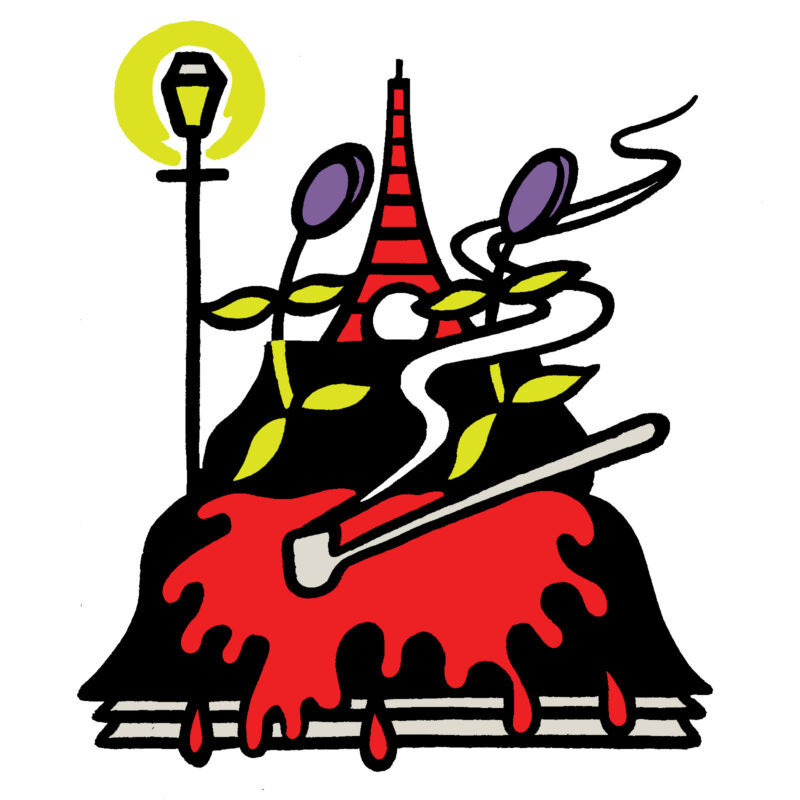

As often happens in drug-induced reveries, the sentences themselves make sense but the connective tissue between these hashish films often seems to be missing or elided, compounded by the author’s unorthodox spelling. As Szittya acknowledges, “I have stolen myself from a film. Now I am strolling along the ocean shore. And I still have not spliced my paragraphs into the proper order.” Like in the sordid tales of fellow Hungarian Géza Csáth, author of Opium and Other Stories, Szittya’s Paris is a province of the demimonde—a midnight city of brothels and sleazy hotels, pimps and prostitutes, a place where boredom blossoms, black tulips frolic, mountains neigh, and blood paints waves of rain. Nonetheless, Szittya manages to complain: “I never have enough images.”

That so little of Szittya’s work has been translated into English thus far is not surprising, given the towering legacy of Cendrars, the anti-bourgeois ambivalence of his fiction, and the provocative, sometimes grotesque images he employs—a relic of the casual prickliness of the interwar avant-garde. The effect may be slightly confused, but it is not without its charms and minor epiphanies.

“The world is only beautiful,” Szittya insists, “when it has no purpose.”

Publisher: Wakefield Press Page count: 80 Price: $13.95 Key quote: “Out of my sadness I paint garish posters for illuminated dilapidated houses. My train has just steamed off with a spring landscape. It is hateful to be a clown.” Shelve next to: Guillaume Apollinaire, Hugo Ball, Blaise Cendrars Unscientifically calculated reading time: The time it takes streetlight cleaners to cycle through Mark Twain’s top hat