When I was nineteen or so, Richard Nichols, a man who was more of a father to me than my own father was, invited me to Electric Lady Studios in New York to watch Amiri Baraka record one of his new poems. Richard, who managed the Roots until his death, last July, was a jazz savant, and during his college years was a poetry student of both Amiri Baraka and Sonia Sanchez. Like Richard had in his youth, I had cultivated an interest in all things poetic, black, and avant-garde. So when he called and said that Baraka had agreed to record a poem for the Roots’ album, and that he had already reserved and paid for my Amtrak ticket to New York City, I packed my backpack and headed to the station.

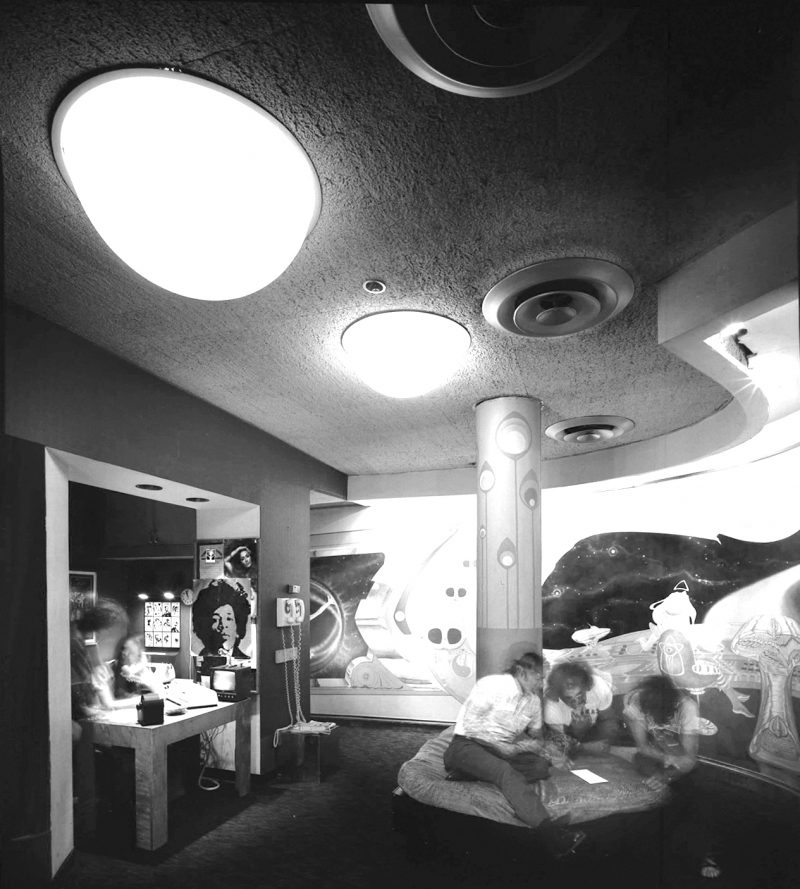

I had been Richard’s “intern” for only a few months, but my internship was a strange one. In the morning I answered the office phone and in the afternoon Richard taught me about old music he loved: Rufus Harley, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Jimi Hendrix. They were the blueprints, the models to study. Over the years, Richard had developed a quiet philosophy of freedom and self-determination and, with very little money, had somehow mentored and raised an informal village of rappers, singers, and musicians: Jill Scott, Erykah Badu, Mos Def and Talib Kweli, Santigold and Bilal. I wasn’t a musician but I came to Richard a confused kid—a black kid who felt very black but wasn’t particularly interested in the kind of blackness that the local radio stations seemed to be shilling—with no idea of what I wanted to do next. Richard, a man of zero sentimentality, rescued me by allowing me to learn about black music and culture as living histories rather than parts of a storied past. From him I knew that Electric Lady Studios was seemingly the only place in a constantly evolving city and an increasingly digitized recording industry that still somehow preserved the psychedelic sensibilities of its first owner, Hendrix, the god himself.

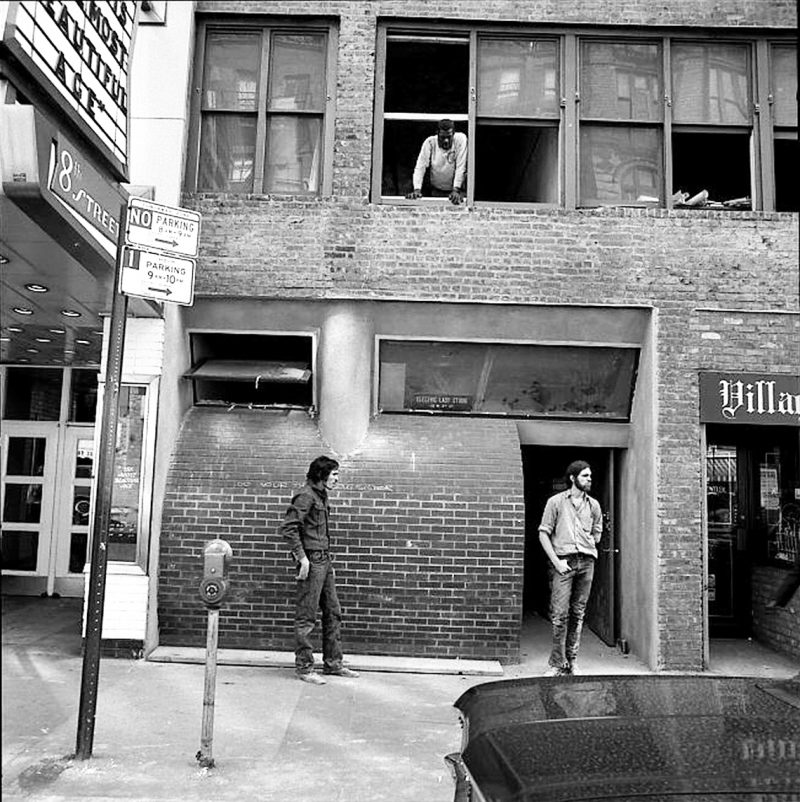

Jimi Hendrix had initially wanted to turn the two cavernous bottom floors of 52 West Eighth Street into a club, like it had been when he first visited the space. For almost forty years it had been the Village Barn, a novelty western-themed bar, and then, for a brief time in 1968, a nightclub called the Generation Club (you can watch videos of Hendrix sitting on the side of the stage there while Janis Joplin sings). It was Eddie Kramer, Hendrix’s mix engineer, who suggested he found a studio—a place where Hendrix could have some financial and artistic autonomy—rather than a club, which Kramer...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in