I visited Michael Heizer’s City for the first time in my dreams, twenty-seven years ago. I was twelve years old, living with my family in Kuwait, when I started to experience a recurring dream where I found myself wandering, naked, through an unfamiliar city, engulfed in shame, desperately seeking a wall to hide behind—but none existed. The city’s landscape was a blend of concrete ruins, sandy dunes, and winds that deepened my embarrassment with every gust. It was an abandoned city without visible inhabitants, yet I felt their eyes peeping at me. With no walls to shield its secrets, the city should have been an open, liberating space. Instead, I wandered, immersed in my shame, hopelessly seeking refuge.

I never shared this dream with anyone; it was etched into my memory as the ultimate image of embarrassment and shyness. Naked in a city without walls.

In my twenties, I learned through reading psychology books that such visions—constructed around shame and body vulnerability—are frequently associated with the adolescent phase of boys’ development. I felt satisfied with this explanation; however, my dream city continued to haunt me as an allegory. I kept looking for it in literature and art—until two years ago, when I stumbled upon a story in The New York Times about City, a monumental art project Michael Heizer has been working on for over fifty years. The report displayed the first-ever photos and videos of this enigmatic “sculpture,” which few had ever visited.

For me, it looked intimate and erotic, a solid, smooth egg floating over a milky ocean. I shivered as I looked at those images, and felt a terrifying sense of déjà vu. Seeing one’s dreams materialize into someone else’s life’s work is an unnerving realization.

I grew deeply fascinated with City, which was made available to the public in 2022, though visits are possible only during its open season, which typically lasts from May to November. During this period, only six people may come per day, and on only one of three days each week (Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday). To arrange a visit, one must fill out a reservation request form and submit it to the Triple Aught Foundation (TAF), a nonprofit organization based in Nevada that owns and operates City. If your application is selected, you then receive further instructions.

Through friends in Las Vegas, my name eventually landed on the waiting list. The invitation started with a message asking if I could visit on June 6, 2023. I answered “yes” and then received emails with forms to sign and instructions to follow. Among these was an important warning: “Unfortunately, no photography or videography is permitted on-site.” TAF advised us about the heat, recommending we wear sunscreen and stay hydrated. TAF also suggested we use the bathroom before leaving, and bring snacks with us, as the trip to City takes two hours. We would stay there for three hours, they said.

Adhering to the instructions, I left my home in Las Vegas at 1 p.m. and drove north, through the desert, to Alamo, Nevada. Alamo is a small Western town in Lincoln County. The streets are quiet, lined with modest homes and businesses that supply the needs of locals and the occasional visitor. It’s known for being close to the Nevada Test and Training Range and the secretive Area 51, which make it the subject of conspiracy theories related to UFO sightings. But when I got out of the car, I smelled my childhood village in Egypt. I felt a sense of déjà vu, seeing the same unpaved roads, tall trees, and wild shrubs—the unmistakable boredom on the faces of dawdling teenagers.

The TAF office in Alamo was housed in a single-story building and shared space with a local pharmacy. It was a study in minimalism: an open area featuring only a couple of desks. There was a guest book on one of the desks, along with a selection of books focused on Heizer’s art. At the heart of it all stood Ed, a towering figure in his sixties, with a welcoming smile. Clad in blue jeans and a cap, he introduced himself as our tour guide and cheerfully announced that I was the first to arrive.

A part from me, the other visitors had traveled from Oregon: a couple with their young daughter, and another young couple. Ed invited me to take the seat beside him. “Your primary task,” he said, pointing to the satellite phone nestled in the car, “is to remind me to make a call every time we stop.” I did this for him, though he never explained whom he was calling.

We followed the main road for about half an hour before veering onto a rocky path. Ed and I talked about Lake Mead and its declining water levels. We exchanged tips on lakes suitable for swimming, spots to find spring water, and the best places for summer camping. Our discussion was interrupted by one of our Oregon comrades, who asked, “Have you ever seen any lights at night?” It took me a moment to grasp what he was hinting at, but Ed, with his experience, quickly replied, “Oh yeah, we encounter weird lights around here all the time, right?” He turned to me for confirmation. Fully aware of the importance of alien tourism to Nevada, I affirmed, “Absolutely.”

We stopped in front of a sign that read BASIN AND RANGE NATIONAL MONUMENT. It was our last chance to take pictures, so we did so in front of the sign, to document our trip. Then we continued driving, passing green wild grass and calm cows chewing alfalfa. There were metal water tanks for the cows to drink from and mountains in the distance. After the land was colonized and its people—the Nuwu (Southern Paiute) and Newe (Western Shoshoni)—were displaced, settlers had tried to build a dam that eventually failed, leading to the abandonment of the land. In the 1970s, Ed’s grandfather recommended it to Heizer. He then transformed it into his residence and the center for his artistic projects. Ed grew up knowing Heizer and in recent years began taking care of his ranch and cows; his stories painted a picture of a peaceful life shaped by isolation and the land’s rustic beauty. The depiction did not exactly resemble Heizer’s own characterization of his life in the valley. In an interview with The New Yorker, he told Dana Goodyear: “I like runic, Celtic, Druidic, cave painting, ancient, preliterate, from a time back when you were speaking to the lightning god, the ice god, and the cold-rainwater god. That’s what we do when we ranch in Nevada.”

Michael Heizer was born in Berkeley, California, in 1944. He was an unusual kid, and his family came to the conclusion early on that formal education did not suit him. So when he was twelve years old, they gave him a year off from school, and he traveled with his father, Robert F. Heizer, an archaeologist and historian, to Mexico. His father would dig, and the kid would do the site drawings. Dr. Heizer was the head of the anthropology department at the University of California at Berkeley; his most significant breakthrough was in 1968, when he discovered La Venta pyramid in Mexico.

This early childhood trip was influential for young Heizer. As William L. Fox wrote in his book Michael Heizer: The Once and Future Monuments, “The sculptures of [Heizer] are never far from the intellectual and aesthetic lessons learned while accompanying his father to sites such as temple monuments in Egypt.” What exactly were these lessons? His father was interested in religious monuments. Perhaps young Heizer thought that gods had made these giant monuments, or that they were made for gods. Or maybe, standing before these expressions of power, he thought something else entirely.

In 1965, Heizer arrived in New York City as a young American artist. He found himself in the company of Walter De Maria and like-minded artists such as Carl Andre and his future adversary, Robert Smithson. This group was united in its quest for a more expansive canvas, far beyond the confines of gallery walls.

Smithson, a particularly influential figure in this circle, was not only an artist but also an influential writer and speaker. His writings from the 1960s—especially the 1967 article “A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey”—reshaped perceptions of landscapes and were pivotal in the early conceptualization of Earthworks, a movement aimed at integrating art with natural landscapes; the concept would later evolve and become known as Land Art.

Heizer’s presence in New York did not last long. He went west to Nevada. It was here that Heizer created Double Negative in 1969 and 1970. This monumental work, which became a Nevadan landmark, consists of two colossal rectangular trenches carved into the desert landscape. It was a feat of both artistic vision and engineering, involving the displacement of 244,000 tons of earth and rock. Heizer’s bold move, from the intellectual art discussions in New York to the physical creation of art within the American landscape, marked a significant chapter in the story of Land Art, and cemented his legacy as a pioneer in the field.

After an hour of driving on dirt roads, our car stopped before a metal gate. Ed stepped out to open it. “For security,” he explained, although it was hard to imagine a trespasser in such a place. He pointed to a large house standing a mile away in the valley, identifying it as Heizer’s residence. From this distance, we could see solar panels and a gigantic yellow crane—one of Heizer’s art tools used for lifting, cutting, and shaping the large rocks he works with. The whole valley was his studio, and these construction machines were his art arsenal.

Heizer bought the land in Garden Valley with a loan from the art collector and his patron Virginia Dwan (1931–2022) and moved there in 1972. At first, he lived in a trailer while he built his house, and he began work on his life’s masterpiece in the backyard. It was also during this time that he traveled with his father to Egypt, a journey that profoundly influenced him. Several art critics have noted the connection between Complex One—the first structure he built in City—and the Step Pyramid of Djoser.

I’ve never much admired the Djoser pyramid, which is in Egypt, where I was born and lived most of my life. For archaeologists and Western visitors like Heizer and his father, the Djoser pyramid is revered as the first pyramid, dating back to the twenty-seventh century BCE. It signifies a pivotal shift in construction from mud brick to stone. For me, it represents another piece of state propaganda that I find suffocating. When I gaze upon the Djoser pyramid, I don’t see gods. Instead, I see the echoes of the first civil war in history, following the collapse of the second dynasty. I see the ascent of the third dynasty under Djoser, whose path to the throne remains mysterious. It was during his reign that the structures and laws of the more centralized authoritarian state were established, demanding people’s taxes and labor to erect massive monuments glorifying a single man who saw himself as both the state and a god.

The old Egyptian rulers used to be buried in the south, in the holy city of Abydos, where gods were also buried, according to Egyptian mythology. But starting with Djoser, kings became the new gods, and rather than being buried in Abydos, they began building pyramids in the north. The holy wisdom of Abydos and the decentralized communities were fading, dissolving into the Nile with their mud bricks. Djoser marked the emergence of a new state and new deities.

As we approached City I began to think about all the new American gods around me now. The gods that had emerged out here in the Nevada desert after World War II: atomic bomb deities, military and air force deities. Here was evidence, all around, of this state’s power. And then, in the middle of all that, a monument.

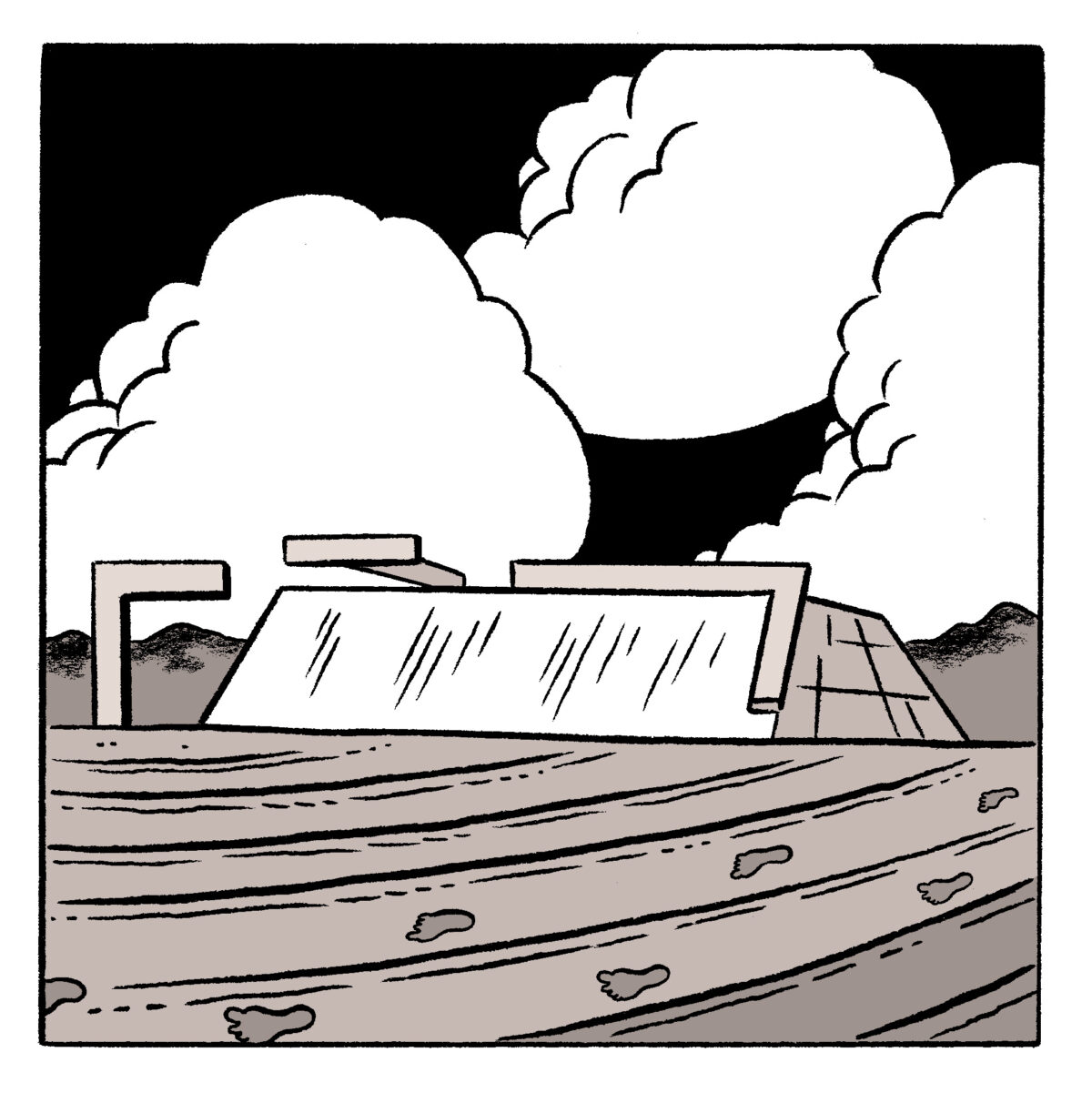

Upon our arrival at City, Ed pointed to the left and announced, “Here is Complex One, the first structure built in City.” Complex Two stood right beside it. Then, gesturing to the right, he added, “And over there is 45°, 90°, 180°.” He cautioned us against climbing the rocky slopes, warning that they could be hazardous, but otherwise, we had three hours to explore as we wished. When someone in our group asked why Ed would not be joining us, he replied, “Because they know you’ll have questions, and they’re afraid I might give you a silly answer that could influence your experience.”

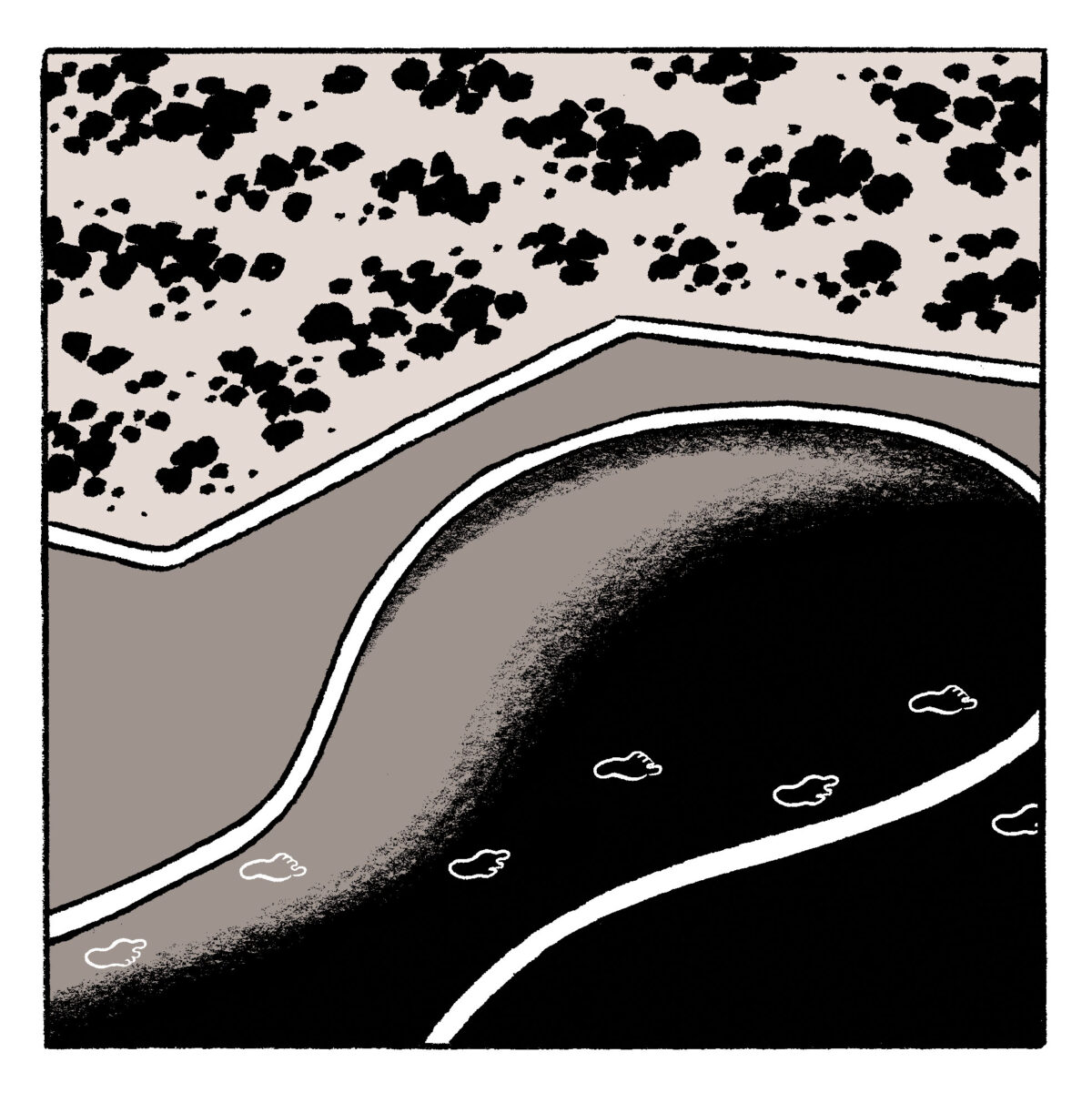

City lacked any signs or labels, but to me the most striking feature was its lack of gates or walls. The others decided to start by exploring Complex One, considering it was the first construction erected and thus the beginning. I bid them a temporary farewell and walked toward 45°, 90°, 180°. With each step, my heart flickered; with every stride, I felt as if I were delving into my past, a distant one, before the revolution, the prison, the exile that shaped my current life. I was transported back to my teenage dreams, and a gentle dizziness overwhelmed me.

I climbed to the highest point near 45°, 90°, 180°, from which I could see the whole sculpture. But when I reached the top and looked down at City, I saw a body. A body lying in the valley, its contours smooth, devoid of sharp angles. Its “skin” was made of various pebbles, with roads weaving over and around the rocky, fleshlike dunes. In the middle of this body was the “city” center, a small green island of grass, the only living plant that was allowed to grow within the work. It’s the first thing you see when you enter and exit City. I thought of it as a belly button; however, from my elevated vantage point, it transformed in front of my eyes into a dry cup… a holy chalice.

Layers of interpretation stacked upon one another, open for exploration. I was absorbed in the art, walking within the very body and existence of the artist. City, with its abstract mounds, prismoids, arenas, ramps, and pits, resembled veins and arteries, bulging muscles and sagging fat—a body aging yet dreaming of immortality.

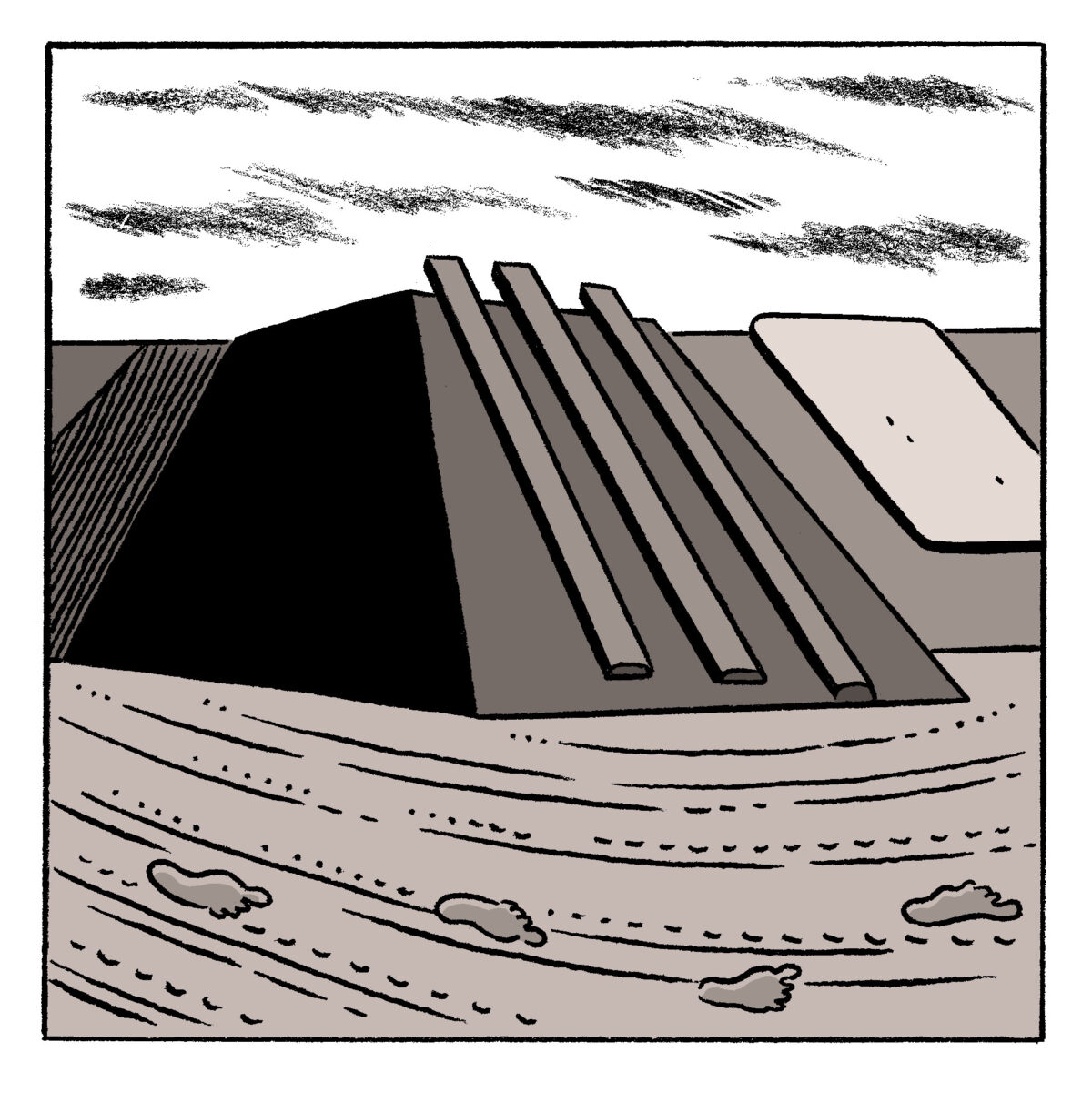

I descended with a mix of reverence and awe into 45°, 90°, 180°. It’s the only space in the city with a concrete floor. The entrance evoked poignant sadness—it was a shrine, a tomb, a eulogy. The arrangement of shapes unfolds in a deliberate sequence. Initially, one is met with a pair of small concrete triangles, setting a stark geometric tone. This prelude is followed by three larger triangles, leading to a group of four towering triangular structures. Beyond these, two contrasting cubes add to the complexity of the space. A path leads to another trio of triangles, and guides the visitor farther into the heart of the complex. At the end of this concrete spectacle stands a splendid concrete wall with two triangular arms at each side, embracing a trio of rectangular concrete blocks. These blocks resemble tombstones, and suggested to me the presence of death. Notably, one block leans against the wall, creating a triangular void, an architectural whisper. All I could think of here was death and desire.

I set my backpack on the ground, removed my white T-shirt, followed by my pants and underwear, and stepped into the shrine, naked except for my sneakers. Streams of cold air poured through the gaps between the concrete triangles, giving me goose bumps, even as the sun provided a blanket of warmth. As I marched naked through these triangles, I wondered: Are the goose bumps a result of the chill? Or are they born of nostalgia or euphoria? Admiration or sexual arousal?

When City opened, it became one of the world’s largest artworks. However, the artwork is not limited only to its structures; it’s an interactive performance that requires participation and adherence to its rules, starting with signing an agreement. TAF selects and invites you, and then you must travel by airplane and car to be picked up as a guest by a driver. It’s a gesture of generosity, of course, but it also implies that once you’re there, leaving on your own isn’t an option.

Inside City, you don’t merely experience Heizer’s devotion and the magnificence of his vision; you feel his authority, his force. Its vastness overwhelms your senses, making it difficult to comprehend its limits. Georges Poulet, the Belgian literary critic, thought of sculpture as an unrevealed secret. You want to circle a sculpture because it gives the illusion that there is something in it that, from a different angle, you might be able to see. But in Heizer’s City, the sculpture is circling you. For three hours, you are subject to its gaze.

What can you do in front of such power? Do you kneel or rise?

I walked toward the concrete tombstones, and when I got close to them, the sky erupted with the cries of ravens. A duo carved through the air, their wings beating furiously against the wind. I thought they were greeting me, perhaps as part of this “art show”—after all, every graveyard needs its blackbirds. Then I saw they had their nest above the rectangular concrete headstone. They were guarding the sculpture that had become their home.

As I walked around 45°, 90°, 180° naked, I was surprised to see red and black marks. Someone had written a date: 7/24/03. There were red lines on another surface and the word CRACK written in black. To me, the human marks spoke of the relentless passage of time, to a crack that had been made in this monument.

In one corner, I noticed piles of rat dung. I imagined desert rodents seeking refuge here at night or escaping the relentless summer. I felt a heightened awareness of everything. I hadn’t expected life to make itself known in City, which has been meticulously maintained to prevent natural growth. Ed told me later that around five employees are responsible for its maintenance, which involves, in part, removing grass or weeds that sprout, to preserve the work’s rocky aesthetic.

Among the rat dung, something shone like gold. When I got closer, I realized it wasn’t gold but scores of scorpion tails. The mystery unraveled when I looked up again to the raven nest and saw a third tiny raven. The ravens feasted on scorpions and desert rodents, leaving their leftovers scattered below. City cost forty million dollars to build, and forty million has been put in a trust to maintain it—which means preventing nature from taking it over—but all that couldn’t stop an ecosystem from establishing itself within its territory.

Suddenly I heard a loud explosion. In a panic, I hurried to get dressed while searching the sky for the source of the sound, but I couldn’t see anything. Then I remembered Ed mentioning that aircraft from Area 51—which is about seventy miles away—often break the sound barrier. Disturbed by the presence of military aircraft, I hurriedly finished putting on my clothes. After dressing, I took out my notebook and tried to jot down some notes, but waves of emotion prevented me from writing anything. Instead, I sketched some drawings of the area and a diagram of 45°, 90°, 180°. An hour and a half had already passed when I picked up my things and walked to Complex One.

It should be about one and a half miles from 45°, 90°, 180° to Complex One, but it feels longer than that due to the undulating terrain of the road, which takes you on paths that aren’t visible when you set out. After a while, I lost my sense of direction and began to feel detached from reality. Eventually I noticed a few of the other visitors, ghostly figures passing by in the distance. Even as I waved to them, I questioned if they were merely mirages.

In front of Complex One, I knew immediately the connection to the Djoser pyramid was far from accurate. However, I understood why art critics, who might have seen Djoser only in pictures, made the connection. Building pyramids started with constructing steps above a tomb. Then one step became two steps, and so on, until there was a pyramid. Complex One is just one step and is not made from mud bricks, like the early pyramids, nor from carved stones, but rather from modern construction materials. Heizer claims to use materials from the land around him, but I don’t think concrete and iron naturally grow in the valley.

What gives Complex One its character is the T-shaped concrete structure that stands in front of and above the step. Its shadow on the step makes it appear to be a container: a womb, a birthplace from which everything starts. From Complex One, you can’t see 45°, 90°, 180°—just as, when we are born, we cannot predict our journey’s path. But from 45°, 90°, 180°, you can look back and see your whole life, the roads you’ve walked, the shadows in the valley, the illusion of your life’s achievements.

As our three-hour visit neared its end, I found myself sitting atop a hill, inhaling the spectacle of the sunset as it wove its shadows and hues across the city. I meditated on the experience of traveling out here. The work changes every minute, depending on the sun’s position in the sky. Moreover, it’s not open at night and cannot be visited at any time during the year. Could I truly claim to have visited or seen City as I had “seen” other pieces of art?

Given that only six people are allowed per day, fewer than one thousand visitors come to City annually. This means that, if everything goes as planned, fewer than one hundred thousand people will have the opportunity to visit in a century, which raises clear questions about accessibility. Each visit to City offers a unique experience. If two people visit City at different times during the year, they will see different artworks. Still, they will experience the same interactive performance art in which they enter Heizer’s domain.

I admire Heizer’s dedication to creating work that aspires to match the grandeur of ancient monuments in Mexico or Egypt, a goal he has undoubtedly achieved. Both Heizer’s City and these historical monuments represent a combination of political power and wealth, serving to immortalize their creators. Some of the names of the workers who built the Giza complex have been preserved, with records that detail their conditions and schedules. However, when I researched Heizer’s project, the only names that appeared alongside Heizer’s were those of supporters, organizations, and donors, including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Dia Art Foundation.

Additionally, Heizer’s project received political support, notably from Harry Reid, the long-serving Nevada senator and leader of the Democratic Party. Since military bases encircled City, several military and nuclear projects threatened its continuation. However, Reid and Heizer consistently leveraged their political connections to oppose such projects, compelling the federal government to abandon its plans. Ultimately, during the last years of Obama’s presidency, Reid helped push through an executive action designating Garden Valley and the surrounding area part of the Basin and Range National Monument. This granted Heizer’s organization a unique legal status: it holds privately owned land that also enjoys special federal protection.

It’s said that during their construction and throughout the pharaohs’ lifetimes, the pyramids were secured places, not open to the public. The authorities wanted to display their power, but only to a select group of privileged people. Nowadays, the pyramids have transformed into tourist attractions, where hustlers might offer to take a photo of you jumping high, seemingly perched atop a pyramid, for a twenty-dollar fee.

I’m uncertain if Heizer’s City will undergo a similar transformation, but he is currently involved in a project in AlUla Valley of the Arts in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. There, His Royal Highness Mohammed bin Salman is investing billions of dollars to install monumental artworks in the Arabian Desert, with the goal of immortalizing his name and attracting tourists.

The sun was coloring the sky orange. The air was unbelievably fresh. I told Ed that I envied him for living here, surrounded by all this beauty and cleanliness. We were waiting for the rest of the visitors to come out when I started noticing circular patches on the ground, empty of grass. They looked geometric and precise. I suspected they had a connection with City and asked Ed what they were.

“Ants’ nests,” he said.

He explained that the valley is inhabited by red ants, which build their nests underground. They remove any green grass on the surface and use it to construct their colony below. They even design chambers for the queen to lay her eggs. The juxtaposition of and contrast between the two projects was hard to ignore: an artist builds an empty city, all the while surrounded by ants who are constructing their own city underground.

I came here chasing an old dream, only to find myself in another person’s dream. I tried to deconstruct both dreams to uncover some kind of meaning. But I don’t think the meaning resides in these gigantic constructions or on these gravel roads. Meaning is never inherently present in the sign or in the artist’s biography; rather, it lies in the gap between the signs. It’s found in the connection between the city and its surroundings: the mountains, the military-industrial complex, the presidential executive orders safeguarding it all—and the ant colonies underground, where maybe a young ant is currently dreaming of a city without walls.

Correction: In an earlier version of this article, 45°, 90°, 180° was mistakenly referred to as Complex Two.