I.

The night before he died, I promised my father I would write a book for him. I was eighteen and harboring profound confidence charged with profound grief. He was eighty, and under so much morphine I doubt he even understood.

Not only was I unable to write my father’s eulogy, I was unable to write him a letter for his coffin. All week, in a depressed but strangely sleepless state, I filled a notebook with the same sentence: “A blank sheet of paper is God’s way of saying it’s not so easy to be God.”

II.

The dictionary defines erase as “to scrape or rub out (anything written, engraved, etc.); to efface, expunge, obliterate.” Its Latin root roughly translates as “to scrape away.” These definitions imply loss and destruction. They call to mind Richard Nixon’s audio-tape gaps, the photographic manipulations of Stalin, the Archimedes Palimpsest, the missing fragments of Sappho. Death.

Heidegger practiced erasure as a way to define nihilism (in an indefinite sort of way). In a 1956 letter to Ernst Jünger, Heidegger wrote the term being, then crossed it out: “Since the word is inaccurate, it is crossed out. Since the word is necessary, it remains legible.” Here erasure, or what philosophers call sous rature (“under erasure”), illustrates the problematic existence of presence and the absence of meaning. Crossed out, being becomes unreliable and indispensable at once.

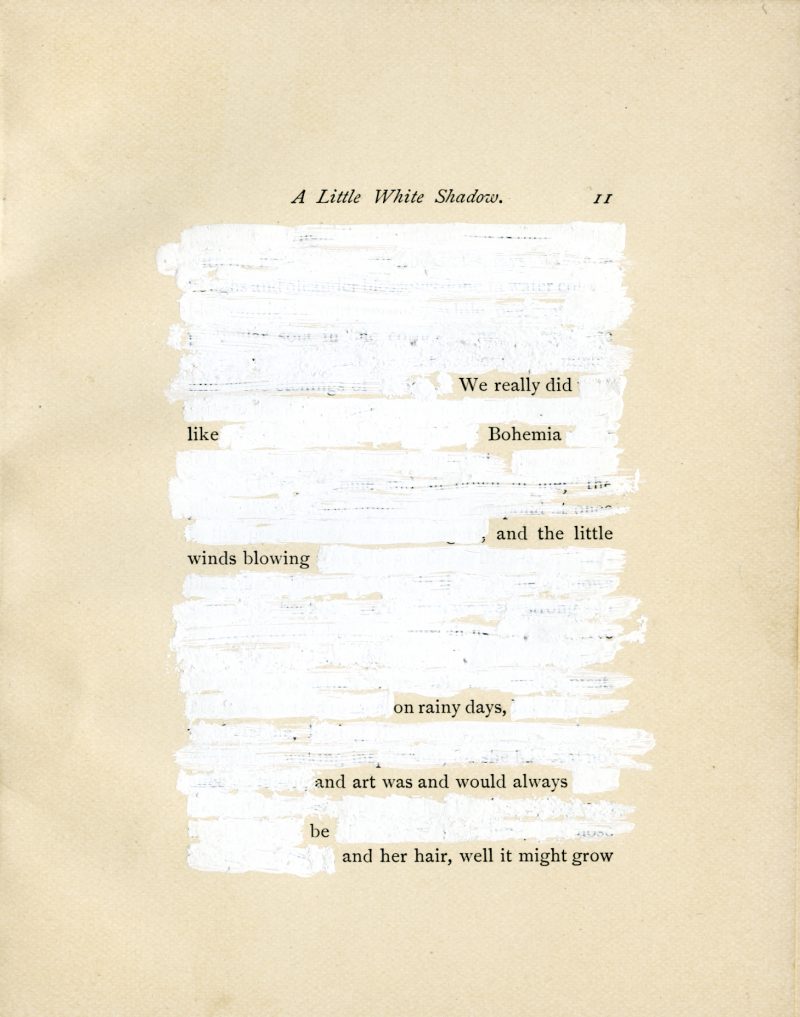

Literary erasure has its own definition. To erase is to create a new work out of an existing one: canonical, obscure, wonderful, terrible, it’s the erasurist’s choice.

When Mary Ruefle whited out select words from A Little White Shadow, an obscure nineteenth-century book published “for the Benefit of a Summer Home for Working Girls,” lines of captivating poetry emerged: “It was my duty to keep the piano filled with roses.” Wave Books brought out a facsimile of her erasure, preserving the appearance of her small, whited-out copy, under the appropriate (and appropriated) title A Little White Shadow. When Jen Bervin ghosted select words in Shakespeare’s sonnets, her own free-verse poems rose to the surface in darker ink:

Against my love shall be, as I am now,

With Time’s injurious hand crush’d and o’erworn;

When hours have drain’d his blood

and fill’d his brow

With lines and wrinkles; when his

youthful morn

Hath travell’d on to age’s steepy night;

...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in