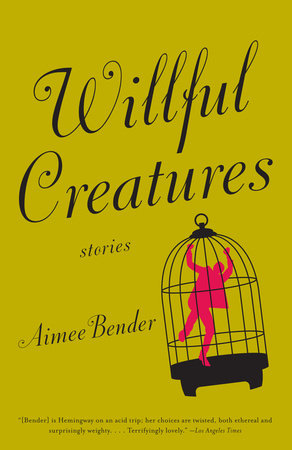

Many of the willful creatures populating Aimee Bender’s radiant second short story collection seem the innocent, cloudy-headed dreams of a child. Potato-children dotingly follow mother as she completes her chores; a miniature man lounges on dollhouse furniture and keeps a pet ant in a cage; a family of pumpkinheads love their oddball ironhead son; and a boy with keys for fingers unlocks doors all over the world.

But it’s not safe and secure. Each story is laced with a bit of arsenic that curls the tongue and sharpens the breath. Narrative storms—loneliness, suspicion, torture, and death—sweep in and electrocute the landscape with jagged lightning. Always unexpected, the events befalling these characters aren’t the whims of a cruel author who enjoys inflicting pain. In fact, Bender feels less the creator of these stories and more a charming hostess who, despite some less than ideal circumstances, makes you comfortable with affable, screwy humor, parlor-room wordplay, and some plain old cute sentences like, “He felt very very tired for four years old.” Many writers try to stand back and let their characters direct the story, but in Willful Creatures, this idea is palpable in the narrative itself. In the best possible sense, Bender doesn’t seem in control.

So who is? “Job’s Jobs” begins: “God put a gun to the writer’s head.” He makes several unreasonable, inexplicable demands in a mobster’s East Coast accent. In “The End of the Line” a regular-sized man hopes to trespass the world of the miniature people, but he feels “disgusting and huge” compared to their tiny furniture and clothes. “Where are the tall people, the fatter people?” he wonders. “Where are the aliens the size of God?” If present in Willful Creatures, God is so inscrutable nearly all have abandoned the concept. Or, they’ve figured the concept will not save, so belief is simply a matter of personal preference.

The most powerful force the creatures feel are the ones within or enacted by others. They seethe and swoon in their roiling emotions, pushing themselves and each other to the nether regions of existence. The character known only as the motherfucker—he literally fucks mothers—teaches a famous actress about desire, a house that needs closed space. “Desire runs out of doors or windows… as soon as you laugh from nerves or make a joke… then you blow open a window in your house and it can’t heat up as well.” Later, she feels “the glass bending out to the night but not breaking, the glass curved from the press of release but not breaking… something buckled inside her and made the longing bigger, tripled it, heavied it… this was not something she knew well, this feeling; she was used to seeing her desire like an angora sweater discarded on the other side of the room. And she felt like she needed him then. In the same basic way she needed other things, like water.”

Of course, Bender has crafted these stories, but to her credit, most of them reveal their stitchings only in the wonderful prose itself, and not the narrative impulse. In that sense, the all-powerful authorial presence is like a black-gloved hand stealthily moving over black velvet; we have to strain our eyes to catch it. But instead of lost, we are left to speculate the feeling marooned or awesome range of human power—how one can so profoundly change the life of another.

—Margaret Wappler