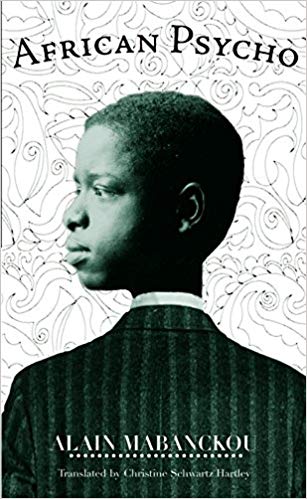

The man who can murder as an act of vanity! As an act of self-expression! The narrator of African Psycho expresses the pathology this way: “to kill at last, crush… I was going to exist at last, that’s it, exist… I was going to be somebody.” Such a lunatic yearning is familiar in fiction, a trick that goes back at least to Dostoyevsky. Likewise familiar is the challenge before the protagonist. The drama’s in the waffling: will he or won’t he? Alain Mabanckou’s novel, the first of three of his books to appear in English this year (the Congolese author has won a number of prestigious prizes in France, including the Renaudot), discovers a fascinating new way to hang readers on those tenterhooks. African Psycho presents no gloomy Raskolnikov, nor the fixed sneer of Patrick Bateman, but a haunted burlesque.

The narrator’s name, Gregoire Nakobomayo, may contain a clash of cultures, colonizer and indigenous, but the man proves easy company. An orphan raised largely in the streets of his African metropolis, Gregoire achieved most of his education via a mashup of comic books and “the prestigious titles of the Pleiade collection.”The result is a voluble palooka, likable, with a knack for car repair and a loyalty not to his city or country, which both go unnamed, but to his shanty neighborhood, very much named, in one of the cleverest of the novel’s frequent onomastics: He-Who-Drinks-Water-Is-An-Idiot. He can laugh at his bouts of drinking and masturbation, and get off snappy put-downs, too.

But lately Gregoire’s thinking has turned from the comic to the noir. He dwells on murder and on one murderer in particular, the legendary Angoualima. This name is another shotgun marriage, part French royal family and part Congo River tributary, and so Angoualima holds up a shadowy mirror to Gregoire.

The “Great Master” of killing had magical gifts: “He lived underground because the worm was his totem… he lived at the bottom of the sea because the shark was his totem… he lived in freight trains because… he was able to turn himself into a package….”

The translation, by Christine Schwartz Hartley, locates an effective balance between the mythic “totem” and the mundane “package”; the dilemma for the story is whether its mayhem-minded narrator can achieve the same. Gregoire talks a violent game and he takes instruction from the ghost of his master, yet he can’t stop asking a very different question: “Where are we going?” His destination may not turn out to be steeped in blood. His delusions of Scarface grandeur (the film’s a hit with Gregoire’s old gang) are belied by the humble and comfortable home he’s made with his intended victim, the prostitute Germaine. And on those few occasions when Psycho depicts actual rather than imagined violence, it generates a chilling verisimilitude as powerful for its hesitations as for its blows and cries.

Mabanckou’s sprightly negotiations of extremes and opposites demonstrate anew how the novel form is nothing if not flexible—a significant demonstration given the book’s provenance. The author, who has been called “the most prolific contemporary writer in the French language,” breaks with the norm for novels out of Africa, these days. Celebrated cases like Uzodinma Iweala’s Beasts of No Nation and Aminatta Forna’s Ancestor Stones have been documentary at bottom; what matters most is getting the pain right. But this splendid freak show reminds us that no novelistic record of sensibility (especially an entire continent’s sensibility) can be complete without its Dionysiac yawp.