Listen to this story:

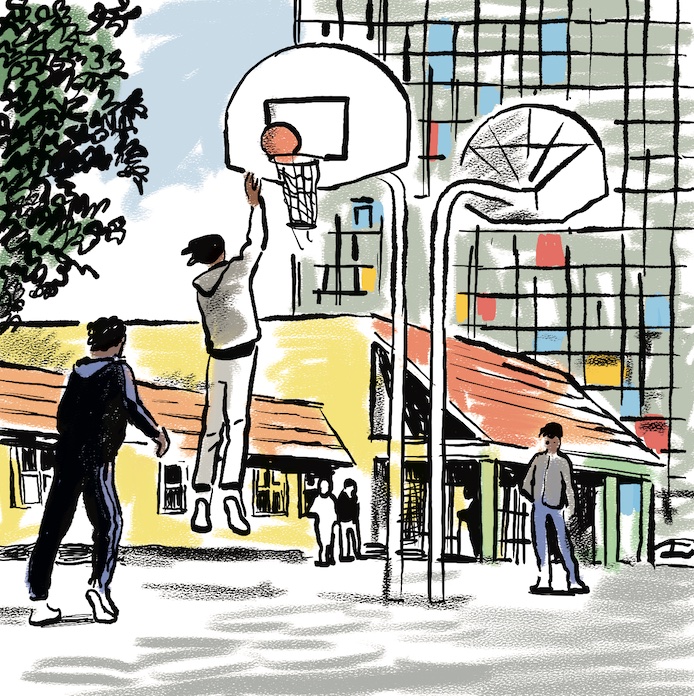

Cedar-Riverside was humming. The boys were looking fresh—Frenchy with his hair twisted up, Saiid’s beard trimmed tight—everybody edged up and faded up and straight from the barber’s chair. Once their moms were out of sight, a few boys snugged durags over their heads, and then Wali started talking about how one time his mom caught him wearing a wave cap like that and smack—he pantomimed a big open hand—too hip-hop. Wali had the boys rolling. Relatives were milling in the shadow of C Building, uncles and older brothers and former players slipping cash into the boys’ palms, something for the journey. The boys were doing that teenage-boy thing where their bodies are short-circuiting on adrenaline but they’re trying not to show it, grabbing and slap-fighting and punching a little too hard. Kids were calling down from the balconies, yelling final Somali encouragements, and even Riverside Plaza itself—those looming brutalist towers, born of 1960s utopian public housing fever dreams and then left to molder—even those concrete towers were glowing. A lateafternoon rain had scoured clean the buildings. The towers’ iconic red, yellow, blue, and white panels were popping in the Minneapolis golden hour, the women’s hijabs and headscarves were popping, the boys’ new kicks were popping, everything was looking nice.

The team congregated by the C Building fire exit until a security guard appeared, drawn by the sight of so many teen boys mobbed in his CCTV screen. As the lone white guy and the only adult, I got to vouch. “We’re going on a trip,” I told the guard, which didn’t really explain anything, and he looked at me and shrugged and went inside.

The whole scene boiled over when Coach Weber rolled up in a rented Ford Transit. florida or bust! she’d written on the van’s windows, along with all the players’ names—a thrill of public validation. The boys sent up a cheer and ran toward the van while the moms started fussing. It was really real now: their boys were driving off into the uncharted white world to play basketball.

I was standing by Yaasir’s mom. “They never go anywhere without us…,” she said, trailing off, unsure what her question was. “And now?”

I told her Yaasir was a good kid, a hard worker, and she smiled and nodded, because Yaasir was a good kid, a hard worker, and who could possibly gainsay that? It was not an answer to her question.

Coach Weber was all smiles and Wisconsinite steadfastness as the moms clustered around her, telling her to take care of their boys. But they all knew her; everyone in Cedar-Riverside knew Coach, had known her for years and years.

“You are driving off into the night,” Saiid’s mom told Coach Weber, another statement that wasn’t sure if it was asking or accusing.

“So we can make better time driving,” Weber said. “Anyway, Saiid’s gonna be calling you in five minutes because he misses his momma, who spoils him too much.”

“He is my favorite boy!” Saiid’s mother nearly shouted, taking Weber by the shoulders.

“Well, I’ve got a video of you saying he’s your least favorite boy,” Weber said.

“Yes, he terrorizes me!” Saiid’s mother yelled, laughing, and took a swipe at Saiid, who was mugging at her through the van’s open passenger-side window, having clambered in to claim primo position. She seemed to accept the fact that her sweet little masjid boy was also a big man with a beard who was going off for a week to play basketball with the Cedar-Riverside Warriors, the club team Jennifer Weber had been coaching for years in the heart of Minneapolis’s Somali neighborhood. The Warriors were heading for Orlando, a grand national stage, one that might offer—what?—scholarships, or maybe fame, or, if they played it right, they could at least score a few girls’ phone numbers. Above all, the boys were looking to redeem a season defined by tragedy—a hard few months since March.

Saiid’s mom threw up her hands in faux exasperation, then presented Coach Weber with a headscarf of her own, a benediction for safe travel, and now it really was time to go—even Mustafa Jack had finally made it, loping up late as usual. The boys, with their neck pillows snapped tight, started piling into the van. A few were in their warm-ups, which all bore Abdiwasa’s number on the sleeve: #10. There were twenty-one of us—players and coaches and JV kids acting as support staff, jockeying for seats in the Transit and in an additional sedan and minivan, elbowing one another, singing, ravaging the cache of snacks even before the van had left the parking lot. The side door hung open as family members ran alongside waving, and then our mad caravan launched into the July night.

The Twin Cities, as Minnesotans are quick to mention, are home to the largest Somali population in North America. Some people refer to the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood in Minneapolis as Little Mogadishu, although whether this nickname is used affectionately or derisively depends on the speaker. Cedar-Riverside supports an ecosystem of mosques and businesses and restaurants and malls where the roughly sixty-seven thousand Somali people in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul metro area conduct their daily affairs. In 2023, Minneapolis became the first city in America to publicly broadcast adhan, the five daily Muslim calls to prayer. The Somali community is both well integrated—with city council members and legislators and prominent business leaders—and culturally distinct. When I moved to Minneapolis in 2015 and began exploring my new city, I realized it was not uncommon to see women in hijabs and abayas walking through town. As an outsider I was intrigued by the contrast: blindingly white Lutheran Minnesota as a hub of the Somali diaspora, the land of May blizzards and Nordic ski culture playing host to immigrants and refugees from a desert civil war. It was the kind of pat observation a newcomer is liable to make about a place.

In recent years it has been especially fraught to be a Somali person in Minnesota. In 2016, Ilhan Omar—who was born in Somalia and immigrated to Minnesota as a teenager—became the first Somali American lawmaker in the US, due to the strength of the Cedar-Riverside electorate. This dovetailed with Donald Trump’s initial presidential campaign, during which, to enthusiastic applause from his rally-goers, Trump slandered Minnesota’s Somali migrants, calling them a “disaster” for the state. Trump’s 2020 reelection bid featured an expansion on this rhetoric: Minnesota was a “refugee camp” filled with “criminals”; Ilhan Omar was a “disgrace” who should be sent back to Somalia.

High-profile criminal trials also fomented ill will against the Somali community. In 2016, the nation’s largest terror recruitment probe resulted in the convictions and guilty pleas of nine young Somali men in Minneapolis who had been accused of trying to join ISIS. In 2017, a Somali American police officer named Mohamed Noor accidentally shot and killed a white woman who had placed the 911 call to which he was responding. Noor became the first Minnesota police officer convicted of an on-duty murder, despite the state’s long history of cops killing people of color. Anti-Somali harassment flourished. In 2018, two Somali men in Saint Cloud walked out of the YMCA to find deer carcasses left on the hoods of their cars. In 2020, after winning Minnesota Teacher of the Year, Qorsho Hassan found herself the target of racist MAGA slurs as she walked through Duluth. Men drove from Illinois to bomb a Somali mosque in suburban Minneapolis. The last few years have seen still more Somali mosques set ablaze, still more Somali businesses vandalized.

Sometime during my early years in Minneapolis, I heard about a traveling club basketball team from Cedar-Riverside, a group of high school–aged Somali kids coached by a local teacher, who also happened to be a white lady from Wisconsin (and if there is a cultural marker in Minnesota more charged than Somali, it is Wisconsinite). I was intrigued. At the time, I was coaching my nine-year-old in rec-league basketball and thought I might learn something about how to run a team. I began attending games, bringing my kids to watch, and started following the team on social media. They played fast. They were loud. I attended one game where the ref clearly despised them, dishing out petty technical fouls, his push-broom mustache atwitch each time one of the boys drained an ill-advised pull-up three. I am a lifelong basketball junkie with a mild antiauthoritarian streak, and, as such, their general gameplay shot lightning bolts into my limbic system. Eventually, I approached the coach with an idea: What if I embedded with the Cedar-Riverside Warriors for a season in a journalistic capacity? The team’s story was an essential one, I argued—an American story, a Somali story, a narrative of migration and integration, xenophobia and community, sports and brotherhood.

Coach looked me up and down. Said she’d think about it.

Abbas was getting churned up. Hands on knees, folded at the waist, head down. Coach Weber was running the Elite team through Hamburger one night at practice, not long before the first tournament. She was not pleased with the team’s general hardiness, and with Abbas in particular. Weber had taken a chance on him, the only freshman on the Elite roster, a team composed of juniors, promising sophomores, and two seniors who had not yet aged out of 17U ball.

“Let’s go!” Weber barked and threw the ball off the backboard, restarting the drill. Abbas tried to leap for the rebound, made small progress against gravity—he was cooked.

I’d met Abbas a few weeks back at tryouts, in early March, where nearly one hundred kids had vied for spots on different teams based on age and ability. Elite—which Weber coached—was the apex. In the gym that day she’d handed me a clipboard and a whistle, offering the thin veneer of authority, and told me to keep my eyes open for anyone interesting. It quickly became apparent that Weber did not need my input. She knew every kid in the gym, had coached their older siblings, knew their parents, asked after their aunties. The younger kids were in a perpetual scramble for her attention.

For two hours, Weber paced the players through 2-on-1s, shooting drills, 5-on-5s, testing their endurance. She clapped and yapped, her demeanor toggling between a kind of gruff maternal heckling and a harder and more exasperated tone. Face-buried-in-hands was a frequent posture, as was arm-around-a-kid’s-shoulders. She employed a rich lexicon of Coach Speak: “If you wanna sit on your butt, go to the bathroom!” I heard her yell across the court at a kid lolling on the sidelines; later she referred to someone as a “bonehead.”

The boys at tryouts ranged from the tiny and dewy-eyed to the strapping and bearded, each attempting with varying levels of success to decode his body’s control panels. Gangly youth in short-shorts sprinted up and down the floor, limbs out of sync and responding to unknowable frequencies. Occasionally a kid might finish a twisting, high-difficulty layup, flush with the insight that his body could function as a vehicle of finesse and refinement, perhaps even grace, before tripping over his feet on the way back down the court. I made notes on my clipboard and tried to look official. A tiny, cocky freshman skittered past defenders in an old T-shirt that read r.i.p. the u.s. constitution. He looked off an open teammate and hoisted a long three-pointer that snapped the net. “Abbas,” I wrote on my clipboard. He turned to flex on his defender, laughing, while his buddy playfully shoved him away.

During the Hamburger session a few weeks later, however, Abbas was not exuding that same swagger. The drill goes like this: Three players wait under the basket while the coach throws the ball off the backboard or rim, forcing them to fight for the rebound. Whoever secures the ball tries to score while the other two immediately become defenders. No fouls are called, which results in a highly physical defensive technique—i.e., two players hacking the shit out of the third as he tries to muscle up a quick shot. Once a player scores, he subs out and a new player hops into the trio. The drill’s name, Weber told me, refers to players getting put through the meat grinder, which was undeniably the case for tiny Abbas.

We’d been running Hamburger for ten minutes by that point and Abbas was trapped, couldn’t make a basket, couldn’t get a breather, was steadily being worn down. Taller boys outjumped him for the rebound. If the ball took a funny bounce and wound up in his hands, two older kids would smash him as soon as he tried to shoot. The first time he took a hard foul, Abbas threw up his hands and looked at Weber.

“You’re gonna get fouled in a game and the ref’s not going to call it.” She threw the ball off the backboard.

Another rebound came to Abbas, another smash, another side-eye at Weber.

“You are not going to get the calls you want,” she snapped. “How are you going to respond?” She threw the ball off the backboard.

Fifteen minutes now. The team was getting restless. Everyone had cycled through the drill multiple times except Abbas, imprisoned under the basket, sapped, his u.s. constitutionshirt soaked and wilting.

“We’ll stop when everyone has scored,” Weber said. She threw the ball off the backboard. “In a real game, you are going to be exhausted when you shoot. You are going to get fouled when you shoot. How are you going to respond?”

Abbas controlled another rebound, got hit, hit the floor, sat there for a moment. Weber spun toward the sidelines. “Why aren’t you picking your teammate up?” The gym had gone quiet. Someone pulled Abbas to his feet. Weber threw the ball off the backboard.

I don’t know how long it took—time began to dilate, as it does in periods of discomfort—but Abbas finally made a basket. The boys on the sidelines gave a halfhearted cheer when his shot went in, relieved to be done.

Weber lit up. “There you go!” she said, clapping, and shook his hand. Then she pivoted toward the rest of the team. “You can go run laps.” The boys stared at her in disbelief. “When your teammate succeeds,” she said, “you celebrate him! When your teammate is failing, you are failing. Think about how to be a better teammate while you’re running.”

At the first practice of the season, Weber had introduced me as an assistant coach, but the boys all knew I was a spy. While considering my initial pitch, she read some of my writing, then brought my proposal to the team; they signed off on my season of participatory lurking with something like a collective shrug: Sure, whatever.

The months sped by as we readied for Florida: practices and games, conditioning workouts, team dinners at Coach Weber’s house. The gym was forever filled with bodies, whether it was the JV team practicing alongside the Elite team, or former players sliding through to talk shit for a minute, get a hug from Coach, catch her up on the family. Younger siblings scurried around the bleachers, emulating big brothers and cousins and working on their handle. The space was abuzz with goofy teen energy, soundtracked by Weber’s playful chirping and snarking. One evening a kid on the team had the bad luck to arrive at practice with a hickey on his neck; moments later Weber was chasing him through the gym, cackling and hooting and telling him his momma was gonna whoop his butt.

Many weekends I drove the boys to and from tournaments, which was surely my most useful contribution as a coach. Abbas usually rode shotgun and took control of the aux cord. He would play Lil Durk for me—a rapper from my hometown of Chicago—cranking the volume until the silky menace of Durk’s trap beats rattled the doors of my eight-seat Chevy Traverse. The boys giddily discussed prom dates, debated who was getting the most yoked from strength training, whose facial hair was too patchy. Drifts of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos dust blew through the Traverse that season, accumulating in seat cushions and cupholders, and clouds of Axe body spray rode along air-con thermals.

We played a tournament in Saint Cloud—the Minnesota city where deer carcasses had been splayed across two Somali men’s cars; the city where, in 2016, a Somali man had stabbed ten people in a mall attack that ended when the man was shot to death by an off-duty cop. Moballer got ejected in the first game that weekend in Saint Cloud. I had never seen the heat of his temper before. He was a sophomore that season, one of many Mohameds in Cedar-Riverside, but the team had differentiated him by nickname—the Mo who was an absolute baller. Lanky and still growing at sixteen, Moballer was a burgeoning star. At the end of practice I would watch him working on his dunks, timing his leap as a friend lofted him the ball. In a few years, he would be selected to the All City Team in Minneapolis and be recruited to play college ball at a Division III school in northern Minnesota. Higher education was often out of reach for these boys for various reasons, money and grades and the necessity of having full-time jobs among them.

Moballer was stoic, often mute, and at the beginning of that season Coach Weber had suspected him of operating in outright defiance of her instructions, before realizing he was partially deaf in one ear and had perhaps not heard much of her coaching. I had seen him in moments of unguarded sweetness, but in Saint Cloud that day, in the final minutes of a tightly contested game against a team of corn-fed Minnesota boys, I watched his anger erupt. During a dead ball, while the ref was turned away, one of the white boys shoved Moballer down, then cut to receive an inbounds pass. Moballer got up, yelling, and walked toward the ref. The ref told him to play on and stop complaining—and then Moballer’s eyes went wild and dangerous, he was cursing out the ref, and then he was gone, booted, the ref barking at Weber to control her players, and Weber suggesting with some force that the ref try calling a clean contest, perhaps one where his eyes were open. That was it: the game was over, having devolved into a series of technical foul shots for the other team, free points, and a demoralizing anticlimax to a winnable game.

This was a dynamic I would come to recognize, a basketball version of the slur “Minnesota nice”—the white boys respectful to the ref’s face, embodying the “kids who play the right way” persona, yet full of cheap shots and stare-downs when the ref wasn’t looking. The Cedar-Riverside boys ran hot, unpolished. They were untutored in the ways of Midwestern nicety. They argued with referees, were generally loud and bumptious and on the receiving end of countless technical fouls and ejections during the season. By the time I discerned this dynamic, I also understood that I had become a crazed partisan, irretrievably galvanized in their favor. Any gesture toward objectivity was a sham.

After the game ended, I watched Moballer stewing at the far end of the bench. He wouldn’t talk to anyone; his face was a stony mask. Then I saw him reach a decision. He got up and stalked toward the ref who had kicked him out. I jogged discreetly after him, trying not to make a scene but wondering if I would need to intervene.

Moballer reached the ref, stood with his eyes on the floor, calmly delivered a message, looked up at him. The ref and Moballer shook hands.

I intercepted him on the way back to our bench. “What was that about?”

“I apologized,” Moballer said, searching my face for what it was that I didn’t understand. “For cursing at him.” Then he went back to collect his gear.

We drove home through the rural night. It was pitch black in the car, and I couldn’t see the boys’ faces, could only hear their voices, bantering first in English, then in Somali, cracking each other up, laughing at their own farts. I was washed in the sound of their camaraderie, cruising along, when I zipped past a state trooper parked on the median. Needlepoints pricked my stomach. My eyes locked onto the rearview to see if the trooper would follow us. Three years prior, a Minnesota police officer had shot a Black man to death at a traffic stop—Philando Castile, murdered in front of his partner and four-year-old daughter. My stomach bottomed out. Until that moment I had not explicitly considered the gravity of my situation: responsible for a carload of young Black boys square in the death-by-cop demographic.

The trooper didn’t follow us. The boys chattered on into the night. I kept to the speed limit. Frenchy was imitating someone they all knew, pontificating with a raised finger, his monologue swelling in bombastic Somali, mimicking the cadences of an imam or politician as the other boys howled. Then Moballer was telling us how he’d congratulated a Wisconsin team by going through the handshake line saying, “Good game, cheeseheads.”

“I don’t think you can call them that, wallahi,” Frenchy said.

“Isn’t that what they call themselves?” Moballer asked, sincerely puzzled.

“Yeah, but, bro, it’s offensive if you say it.”

We reached Cedar-Riverside, and as I aimed for the towers, we passed through an intersection partially blocked by squad cars. The Traverse was washed in flashing red and blue. “The block is hot,” someone murmured from the back.

The team played through Ramadan on empty stomachs. In a gym in Wisconsin, the boys marched past the bleachers, the only Black faces in the room, and headed toward a pile of gymnastics mats in the far corner. Akram opened a mobile app that points toward qibla but couldn’t get service, and so the boys who wanted to pray took their best guess at the direction of Mecca. They removed their shoes, prostrated themselves on the mats, and Saiid led the prayer while people in the bleachers stared at them.

The team’s collective vision was aimed at Florida, prepping for the national tournament. Coach Weber had ordered warm-ups for everyone, personalized with their names and nicknames. On the left sleeve we all wore #10.

In Burnsville, the Warriors won a tournament. The boys looked loose that weekend. On the ride there, Moballer sighed as we crossed the Minnesota River, then deadpanned, “The ocean is beautiful,” a comment that set the car aflame. “Wallahi, you stupid!,” everyone yelling and laughing, kicking the floor, shouting down Moballer’s protestations—“I was joking, dumbasses!”—but this segued into a discussion about who had been out of the state, out of the country: who knew anything of the broader world.

Coach Weber had new uniforms waiting for the team in the Burnsville gym. Saiid, struggling with the stiffly knotted drawstring, went into full class-clown mode, stumbling over his new shorts, pratfalling onto the hardwood. “Coach, it’s not fair, we don’t have these fancy shorts in Somalia!” He was trying to keep a straight face. “We only got leaves to wear!”

Weber was staring at him, hands on her hips. “Saiid, when was the last time you went to Somalia?”

He couldn’t hold the poker face any longer. “Uh, never.”

At the iftar dinners Weber hosted at her house during Ramadan, Saiid would sing the prayers after they broke the fast eating dates, his voice a liquid glissando. He was a maniacal talker and inveterate showman, a seventeen-year-old with an outsize fear of Smelly Melly, Weber’s decrepit and gentle beagle—a routine that was only partly a comedic bit. Whenever the elderly pooch trundled through the room, Saiid would leap onto the couch shouting, then grab me and thrust my body between himself and the dog, yelling, “Screen! Set a screen for me, bro!” In Burnsville that day, Weber had listed the roster on a whiteboard, but next to Saiid’s number she had written the pseudonym “Pain in the Ass.” He was a sharpshooter in addition to a smart-ass, drilled threes all day, and the Warriors won the tournament easily.

This was one of the few times I could remember the team having a fan in the stands. They were almost always the only Black team in the gym, and our section of the bleachers was forever barren. But in Burnsville, a Black woman wearing large BLM earrings wandered in, sat behind our bench, and began cheering for the Warriors. She had no connection to the group. Afterward, she came over to chat with Weber, and then, before heading off to find another game, she winked broadly at us. “I always got to root for the home team.”

The boys’ parents and relatives rarely attended their games, busy with the ongoing labor of being immigrants in America. They worked to establish themselves in the community, in the city; worked to raise their families; had no extra minutes in their days, or had no car to drive to a basketball game in another state to cheer for their boys. We frequently played teams that had large entourages of supporters, whole families that had traveled to fill the stands and roar for their Midwestern sons. Our bench worked to counter this, supplying all the noise we could muster, stomping and clapping and chanting, getting loud when we scored or got a good defensive stop. For this, the boys were repaid with constant hushing and shushing—from the refs, from the other fans; I lost track of the number of Minnesota moms who, from the comfort of the all-white bleachers, would yell “Sit down!” at our bench. They hated the team’s joy, and it filled me with glee to see how these boys refused to let themselves be dimmed.

From the middle of the season, one tournament stands out. There was a pall over that weekend, the boys all pissed at one another and Weber pissed at the lot of them. They got crushed by a superteam with two seven-footers. They blew winnable games. They missed defensive assignments and got into flamboyant arguments on the bench. I had my own kids with me at that tournament—nine and seven and three years old at the time—sandwiched between me and the players on the bench. After a bad defensive lapse, Saiid and Moballer came off the court heated, sat in the available seats on either side of us, and began bickering.

“You gotta communicate!” Saiid kept poking him.

“Get off my dick, bro!” Moballer yelled at Saiid, then to me, sotto voce, “Sorry, Coach.”

“Fuck you!” Saiid retorted, then as an aside, “Sorry, Coach’s kids.”

An increasingly profane call-and-response volleyed across us, my children staring saucer-eyed ahead, the boys alternately cursing each other out and apologizing to us.

A cloud of unease hung over that tournament, which took place just a few days after Abdiwasa’s memorial service. The team had buried him in March, not long before tryouts, but now it was May and the mourning period was over—they’d said dua, prayed for his soul, and it was time to move forward.

Cedar-Riverside is triangular, belted by expressways on two sides and the Mississippi River on the third. The area is choked off from the rest of Minneapolis by major transit arteries, as tends to happen in neighborhoods without many white residents.

In Cedar-Riverside, on the first day of March in 2019, Abdiwasa Farah sat in a Camry with two friends. They were in the parking lot behind an East African restaurant where they’d just eaten, and where we sometimes ate as a team after tournaments. It was nearly midnight and well below freezing, the skyline glittering in the frigid air. The towers of Riverside Plaza loomed alongside them. A car pulled up and two men in dark jackets got out. They fired twenty-six bullets into the Camry, hitting Abdiwasa nine times, seven bullets to the back and two to the head. The shooters fled. The other boys, who had also been wounded, managed to pilot the Camry two blocks before they found an ambulance, but Abdiwasa was already dead.

He was a sweet, skinny boy—Wasa, they called him, #10, the team’s little brother. He radiated a loose-limbed charm that rallied the players around him, eager to hear what hilarious nonsense he might spout next. His charisma found bodily expression in goofball dance moves: here’s Wasa grooving in his security vest as he waves vehicles into the fundraiser car wash; there’s Wasa bopping around to a country band in a roadside bar, the only spot the team could find posttournament to break the Ramadan fast. He was a diligent worker. He stood up to bullies. He was seventeen.

In Minnesota, the conservative media obsesses over the local Somali community, deploying the standard Islamophobic terminology; the rhetoric is ripe with terrorism and jihad, hand-wringing over the onset of sharia law, which is perpetually on the imagined horizon. Cedar-Riverside exists in the conservative imagination as a place of exoticism and foreignness, but Abdiwasa’s death was fundamentally American. He died by bullet, which is now the most common way for a child to die in the United States. His death was the truest manifestation of our American exceptionalism.

The drive to Florida took two days. In Atlanta, the boys got themselves into a friendly dance battle with a group of teens hanging out in Olympic Park. In Gainesville, Weber needed to sleep for a few hours, so the team played a 3 a.m. pickup game at an outdoor basketball court illuminated by the van’s headlights. When the mad caravan at last reached the rental house where we’d be staying, the van disgorged the boys in a state of joyous, jittery cabin fever. There had been a lot of slap-fighting on the drive.

Our rental was forty-five minutes outside Orlando in a swampy exurban subdivision. We were not terribly far from the place where George Zimmerman murdered the unarmed seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin for the crime of wearing a hoodie. I thought about mentioning this to the boys as a precaution, but they were already well acquainted with how to live in a world that viewed them as threats. From the van we carried in box after box of Costco purchases, our food for the week. Weber segregated items for the boys who were religious: the grape jelly was haram, made with gelatin, but the strawberry preserves were halal, just fruit and sugar.

She’d been budgeting for the trip all season, a tricky piece of bookkeeping. Since the Obama administration, the US Department of Justice had been operating CVE initiatives in the Twin Cities—Countering Violent Extremism, a loaded piece of bureaucratic jargon denoting programs whose stated goal was identifying vulnerable young men and guiding them away from radicalization. At the surface level, this often took the form of funding youth groups and after-school programs, but many in the Somali community viewed programs like these with deep distrust—another way for the government to infiltrate their neighborhoods and keep tabs on which teenagers weren’t saluting the flag with proper obeisance. In 2015, an FBI agent in Minneapolis named Terry Albury confirmed these very fears when he began leaking confidential documents showing that racial and religious profiling, intimidation, government overreach, and unconstitutional surveillance networks were woven into the fiber of CVE programming. For his efforts, Albury spent four years in federal prison. Not long after Weber launched the Warriors basketball program, the government invited her to apply for a CVE grant, but she turned down the offer—an act that simultaneously earned her the neighborhood’s trust and left her scrambling for funding. Each year, there were uniforms to replace and warm-ups to buy; vans to rent; and food, lodging, tournament fees, and insurance to pay for—always something unexpected. The entire Florida trip had been underwritten by a series of garage sales and team car washes she’d organized over the year.

No one slept much that first night, skittish and pumped full of Monster Energy drinks. The previous year had been Abdiwasa’s breakout season. He was a budding star on his high school team and a force at shooting guard for the Cedar-Riverside Warriors, who overperformed at their end-ofseason tournament in Las Vegas. The Warriors had earned a mention in the national press, and Abdiwasa’s name began appearing in preseason lists of players to watch in the Twin Cities. This Florida tournament would be his proper memorial, a chance for the boys to honor what might have been. Eventually, I drifted off to sleep on a couch in the common area, my bed for the week, to the clatter of boys playing rowdy dice games and pillaging the fridge and freezer, slamming doors, always laughing. Around four in the morning I woke briefly: Coach Weber had laid a blanket across me and was finally tiptoeing off to bed herself.

Orlando, game one—the first of three that would determine whether or not the Warriors advanced into the elite bracket, where the real teams played and future college stars and NBA prospects showed out on the national stage. I watched Moballer swipe deodorant under his arms before tip-off. Everyone was tense and uncharacteristically quiet. As we located our court for the first game, it was hard not to notice how the other teams stood taller, looked stronger, wore expensive uniforms with their individual names, with sponsorships. There were teams from across the country, from France, from Canada, from Germany. Our uniforms seemed raggedy in comparison: reversible jerseys with no names, mismatched shorts.

Weber pulled the boys into a huddle, saw how nervous they were. Her voice was steely but carried none of its frequent exasperation. “You made it here. That’s something most people can’t say they did.” She looked each of them in the eye. “You made it through the grind, the practices, the strength training. That’s inside you now. You know the plays, you know the trap defense. All you need to do is bring intensity and composure.”

Then the tip went up, and they did; Weber had spoken those words directly into their bodies. Akram tore through the game, undersize but thick, came down the floor like a boulder tumbled loose from the hillside. No one could stay in front of him. He was one of the team captains, a person who moved through the world in a state of perpetual amusement. Each morning that week in Florida, Akram had marched downstairs from his bedroom, a bright smile on his face, and rousted me from my couch-bed with his daily greeting—“What it do, baby!,” dapping me up as I struggled toward consciousness. He was charmed by the world, and it by him. He taught my three-year-old daughter to dribble in the hallways after tournaments, endlessly patient, youngest child of a big family. He was seventeen and a junior in high school that year, working overnights at the airport. He would sleep in his car for a few hours at the end of his shift, around 5 a.m., then drive on to school to flip the pages in his pre-calc textbook. When I told him how impossible that sounded, Akram just shrugged, that bashful, easy smile. “Nah, man, that’s life.”

But Akram couldn’t carry the squad alone. The other team was well practiced and local, playing in front of their own fans. They had just won a regional tournament in Florida, and by halftime the Warriors were down by two points. “You’re going to get hit,” Weber had told them. “How are you going to respond?” Akram dove for loose balls, the bench got raucous, and the ref told us all to be quiet—but this was familiar territory. We were down seven points late when Akram drained a three-pointer. Ninety seconds left, down four. Weber called time-out, set up a trap defense, and the boys forced a turnover, scored again. Down two. Minute to go. But the other team steadied themselves, maintained their slim lead, ran out the clock, and won.

Game two, the next day, was a lopsided victory for the Warriors. The boys attacked relentlessly, hungry to avenge their prior defeat, and as we approached the last five minutes, the Warriors were up thirty points. The bench was getting giddy. Everyone knew what was coming, what had long been promised. It was time for Big G.

Guled, whom everyone called Big G, had been one of Abdiwasa’s closest friends on the team, another top prospect, a tall, shy kid sporting a chinstrap beard that couldn’t disguise his baby face. He had torn his PCL at the end of the previous season and spent the year rehabbing his knee. Although he couldn’t play, he insisted on traveling with the team to tournaments, coming to practice, limping along the sidelines in his knee brace, cheering. “My team needs me, Coach,” he told me. “I need to be there for them.” Mid-season he had surgery to clean up the cartilage in his knee—another thing to heal from—and still he maintained his equanimity, still he carried his sleepy smile through an endless rehab process, still he paced the sidelines where his best friend wasn’t. Then, about two weeks before we left for Florida, the doctor cleared him to practice, although he could barely jog. At that point the petitioning began. Coach was going to get Big G some minutes, right? Wallahi, he’d been working toward it all season. He was coming to Florida—she had to let him play. Right? As the clock ticked down in our blowout, the rumblings on the bench became hard to ignore. The starters were long out of the game and all the young kids had gotten in. Two minutes left, ninety seconds left. The boys were eyeing Guled, eyeing Weber. She stared resolutely away from the bench, would execute the game plan on her own damn schedule. With forty-nine seconds left in the game, Weber called time-out, nodded toward Big G, and the boys erupted. He touched his shoes—LLW, he’d written on them in black marker, “Long Live Wasa”—and hobbled onto the court. He told me earlier he would score a basket in Abdiwasa’s honor if Coach would just let him into the game.

Immediately the team ran a play for Big G, who loped around a screen in slow motion—he could barely move—and was able to lift a long three-point shot. The bench shrieked in anticipation, holding each other back, and the ball clanked off the rim. They flopped back into their seats. A quick rebound and right back to Big G—clank. Each time he touched the ball, the bench gasped, ready to explode, and each shot missed. He got four clean looks in forty-nine seconds: nothing came even close. The buzzer sounded.

Big G looked over at us with an abashed smile—Sometimes it’s not your night, sometimes it’s not your year—but the boys ran over and mobbed him anyway.

We came then to the limit, that place where the timelines branch into what if. If the boys won their third game, on the third day, against a strong Texas team, they would enter the elite final bracket, where their aspirations lay. Lose, and they would play in the loser bracket with the other losers. They all knew the stakes. By the time we were in the van and headed for the arena, everyone had gotten into an argument with everyone else—all the boys were on edge. Then Weber seized the aux cord and put on Adele, turned the volume all the way up to drown out the boys’ interminable bickering. Within moments the players were belting along, and Saiid was in his feelings, doing operatic vocal somersaults to match. It was around this time that the skies opened with apocalyptic fervor, some grand cosmic joke, rain hammering down on the van’s roof. When we’d left the house on that third day in Florida, I was fairly certain they would lose the game, so thoroughly poisoned was the energy—but by the time we’d plowed through the deluge to Adele, I knew we were invincible.

We weren’t. They lost. The boys almost won but didn’t.

The ref came over after the game to compliment us, said we had a real nice team. They lost because life isn’t the movies, no matter how cinematic the thunderstorm, and winning the tournament will never bring your friend back, can’t unbend the arc of your life. They lost, and there was more losing to come. I watched them milling around on the court after that third game, dazed, trying to make sense of it, the comeback that never came. I was watching one of the boys, a point guard who moved like a drop of mercury, who in just a few years would be hospitalized during a mental health crisis. I was watching Moballer and Mustafa Jack, who in two years would be recruited to play Division III college basketball—both would drop out after their first semester, adrift in northern Minnesota, far from the legibility of Cedar-Riverside, drawn back by homesickness and family responsibilities. “The timing wasn’t right…,” Moballer told me later, trailing off, but he would give school another shot—sometime he would. I stood watching these boys who would soon find themselves caught up in the bustle of adult life, working overnight shifts in nursing homes, as security guards, as aides for autistic children, at the airport, or getting degrees in auto repair. They would keep hooping, and I would see them in Cedar-Riverside, where Weber kept everyone in motion, playing basketball tournaments and volleyball and doing fun runs and going ice fishing, as if perhaps they might achieve perpetual motion, moving fast enough to never be touched by the bullets that occasionally slipped through the neighborhood.

Abdiwasa was already lost, but the man who killed him would be found and arrested, convicted of murder two years later. He was legally an adult when he pulled the trigger, although he was barely older than Abdiwasa. That man will live out the rest of his days in prison.

“It could have been me,” Big G told me once, talking about Abdiwasa. “I could have been in the car with him that night.” He went quiet. “I could have died.” I remembered his words later, after Big G himself was gone. A few years after he graduated from high school, he died in a long-haul trucking accident. Big G and his uncle had been running hard hours and the truck went off the road in the night. At the funeral I stared at Guled’s lanky body outlined beneath a thin cotton shroud, resting at graveside, his baby face hidden but the silhouette undeniable, impossibly him. His name is still in the team’s group chat, and sometimes I see it and forget that he’s gone.

There were other games that week in Florida, but they didn’t seem to matter much. The dream was punctured. The boys played well sometimes, poorly other times. Our last game in Florida was a disaster. We drove forty-five minutes back to the rental house in defeated silence. Weber was pissed, her thousand-yard stare piercing the windshield. She was still pissed and still silent when she detoured shortly before our destination, took the van into the McDonald’s drive-thru. At the intercom she ordered twenty-one soft-serve ice cream cones, which the attendant thought was a prank, and so she was extra pissed when she had to repeat herself: “Yes. Twenty-one. Soft-serve. Ice cream cones.”

Throughout the season almost no one had spoken openly about Abdiwasa. He was acknowledged in hints and symbols, his #10 on our warm-ups, the LLW that the boys wrote on their sneakers. One day in Florida we went to the beach and I watched Saiid inscribe LLW in the sand with a piece of driftwood, etching it again and again as the waves erased it. But something broke free in the van that night as we ate our ice cream. Moballer—forever silent and stoic, whose face at rest is a perpetual glower—cracked open and launched into a joyous rambling monologue. For the duration of the drive, he addressed us each in turn, called us by our nicknames, made inside jokes, told us each how much he loved us. It was the most words I’d ever heard him speak. Back in the rental house, the boys were all buzzy and emotional. Moballer had unlocked a long-shuttered gate. We sat around the common area commemorating the season, and the evening soon became an impromptu memorial service for Abdiwasa. Some of the boys spoke about what Abdiwasa’s loss meant. One of Abdiwasa’s closest friends simply put his head down and sobbed, and the other boys rested their hands on him. Some of the assistant coaches—young men in their twenties who’d played for Weber in previous years, and whom she saw as role models for her players—begged the boys to talk, just talk, about their grief, their mental health; these things were still charged and taboo topics in the broader Somali community. Talk with your friends. Find out what’s going on. We can’t lose any more of you.

In the house that night they rallied around one another in their grief, naming aloud life’s daily violences, the fouls casual or axis-tilting. You get hit and you go down, over and over. You’re on the floor. You take a breath, gather yourself. Your teammate has his hand out. You get up.