Taking amusement, even inspiration, in the stubbornness of the elderly is predicated on a rather dark notion. Old person, you are on your way out. There’s no point arguing against your notions, our laughter would say if it had to explain itself, because at your age, notions are not worth changing.

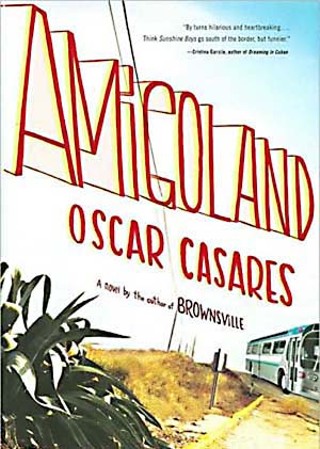

This fatalism is not lost on the two estranged brothers in Amigoland—stubbornness is the moon that carves the tides. It drives the aging Rosales brothers apart, where a sense of fusty fatalism keeps them. Both live in Brownsville, a Texan town on the Mexican border (and the eponymous setting for Casares’s charismatic 2003 story collection). But they haven’t spoken in ten years. The younger Don Celestino, recently widowed, scratches chores over the confines of his calendar lines. His ninety-one-year-old brother, Don Fidencio, has been committed to Amigoland nursing home, where, life being served to him, his memory starts to slip. He engages himself mainly by policing the punctuality of the meal and medicine carts.

When Celestino begins seeing Socorro, his much-younger Mexican housekeeper, he gains a new lease on life. But as is true of leases, it comes with a risk—one he can’t stop worrying about. Socorro wishes to meet his family, and, after hesitation, Celestino seeks out Fidencio and begins visiting him. One thing leads to another, and in part because of Socorro’s encouragement, in part out of brotherly obligation, Celestino steals Fidencio from Amigoland so that the three may journey into Mexico to fulfill Fidencio’s promise to his grandfather to find the ranchito from which he was kidnapped.

Amigoland has the tightness of a short story. The care and humor with which Casares initially pots his characters in their isolated environments afford leisure with plot. (The trio doesn’t board a bus until two thirds through the novel.) Casares grows his characters slowly and organically so that, thriving side by side, their tanglings become inevitable. The characters are so well developed, in fact, that Casares can seamlessly pan multiple perspectives in a single sentence. “He would have put his brother’s medicines in there as well,” Casares writes mid-journey, “but the old man said he didn’t want to arrive in town with his hands empty, like some trampa.” The funniness of a man grasping at dignity by clenching on to his bag of meds is textured with Celestino’s inflection. Old man is Celestino’s term, desperate as he is to differentiate himself from his brother....

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in