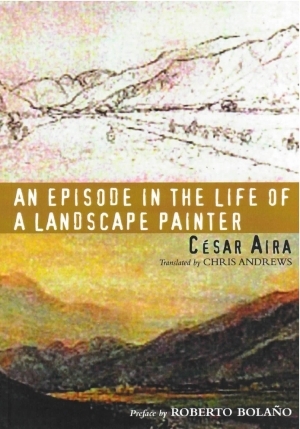

From the torrid landscapes of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Romantic writing to the angels garlanding Rilke’s twentieth-century poetry, the notion of the sublime was useful to both the generation and discussion of art. But with the advent of modernist writers like Joyce, followed by the aftershocks of World War II, this concept lapsed into disrepair as the smart set withdrew into the interior lives, narrative puzzles, and dystopias that infused much of what passed for urgent literature. Possibly not since Cormac McCarthy’s blood-sprent work has there been a contemporary novel such as the Argentine writer César Aira’s An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter—one that stresses the sublime without falling back on the props of magical realism. This fictional take on an actual historical figure is not without its surrealist touches, but such elements arise as a result of, as opposed to being imposed on, the setting itself.

The German artist Johann Moritz Rugendas (1802-1858) won acclaim for his landscape paintings and ethnographic depictions of South American cultures. Then, while traveling through the Andes in 1837, Rugendas fractured his skull in a riding accident, which left him disfigured and neurologically impaired. Reimagining the incidents surrounding this misfortune, Aira depicts Rugendas as a man who, acting against the recommendation of his advisor, the naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, is derailed by his conviction that only in Argentina would he “be able to discover the other side of his art.”

Humboldt is portrayed as an advocate of “artistic geography” who believes landscape art can further naturalistic studies by providing a documentary framework for the study of an environment. The scientifically informed artist labors to render a landscape in its “physiognomic totality.” For Humboldt, this technique finds its most beneficent application in tropical landscapes, with their numerous unique floras. Because of this, he protests at Rugendas’s desire to travel through the pampas of Argentina, believing it a landscape devoid of enough exceptional material to make it a worthwhile object of study.

As with many an exemplary disciple, Rugendas neglects the dogma but not the faith of his mentor’s program. Whelmed by the landscape that surrounds him, his desire to capture it in all its magnificence is frustrated, but persistent. The landscape makes him interrogate his vocation while at the same time holding out the promise that in its challenge rests the apotheosis of his art. The aesthetic challenges Rugendas faces lose their theoretical aspect in a lightening storm in which he and his horse are struck twice. “The horse’s mane was standing on end, like the dorsal fin of a swordfish…. the charge was flowing out of the animal too, igniting a kind of phosphorescent tray all around it…” Rugendas is thrown from his horse, but, with his foot caught in the stirrup, he is raked across the earth in the wake of his bolting animal.

Remade by the landscape, the now highly medicated artist throws himself deeper into his work. Aira shows how the painter, who initially sought objective transparency in his work, is lured on a path toward abstraction. While the novel doesn’t brim over with psychological depth— when the artist tries to communicate with his correspondents, his rather than introspective, and his impulse is declarative philosophic speculations that “art [is] more useful than discourse,” are featherbrained at best—it’s the external reality that enraptures.