On September 30, 1978, a then-unknown artist named Tehching Hsieh locked himself in a cage he built in his Tribeca, New York, loft and remained sealed inside for 365 days. Cage Piece, as the work became popularly known, was the first of five extraordinary and grueling one-year performance works Hsieh made between 1978 and 1986: Time Clock Piece, a year during which he punched a time clock on the hour every hour; Outdoor Piece, a year spent without shelter; Rope Piece, a year spent tied to another artist, Linda Montano; and No Art Piece, a year in which he abstained entirely from making and engaging in anything related to art. In 1986, Hsieh announced he would spend the next thirteen years making art but not showing it publicly (a project known as Thirteen Year Plan); he emerged on the first day of the year 2000 to release a simple statement: “I kept myself alive.”

Born in Nanzhou, Taiwan, Hsieh arrived in the US in 1974 as an undocumented immigrant after slipping off an oil tanker near Philadelphia and hailing a taxi for New York City. For decades Hsieh remained on the fringes of the art world as a somewhat enigmatic and legendary figure. While championed early on by alternative-arts spaces like Exit Art and Franklin Furnace, Hsieh’s work did not receive mainstream recognition until 2008, with the publication of Out of Now: The Lifeworks of Tehching Hsieh, a monograph created in collaboration with the art critic Adrian Heathfield, followed by shows at MoMA and the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and in South Korea, Australia, Brazil, and the UK. In 2017, Hsieh represented Taiwan at the Venice Biennale.

Hsieh’s work endures because of its timeliness and timelessness. This paradox is intentional. When Outdoor Piece was first performed, it was seen by many as a parable for New York City’s poverty and homelessness problems; today, it is just as likely to be interpreted through the lens of the global refugee crisis. Hsieh’s other works continue to speak to, echo, and wrestle with our contemporary moment, from our 24-7 late-capitalist economy to the rise of the carceral state.

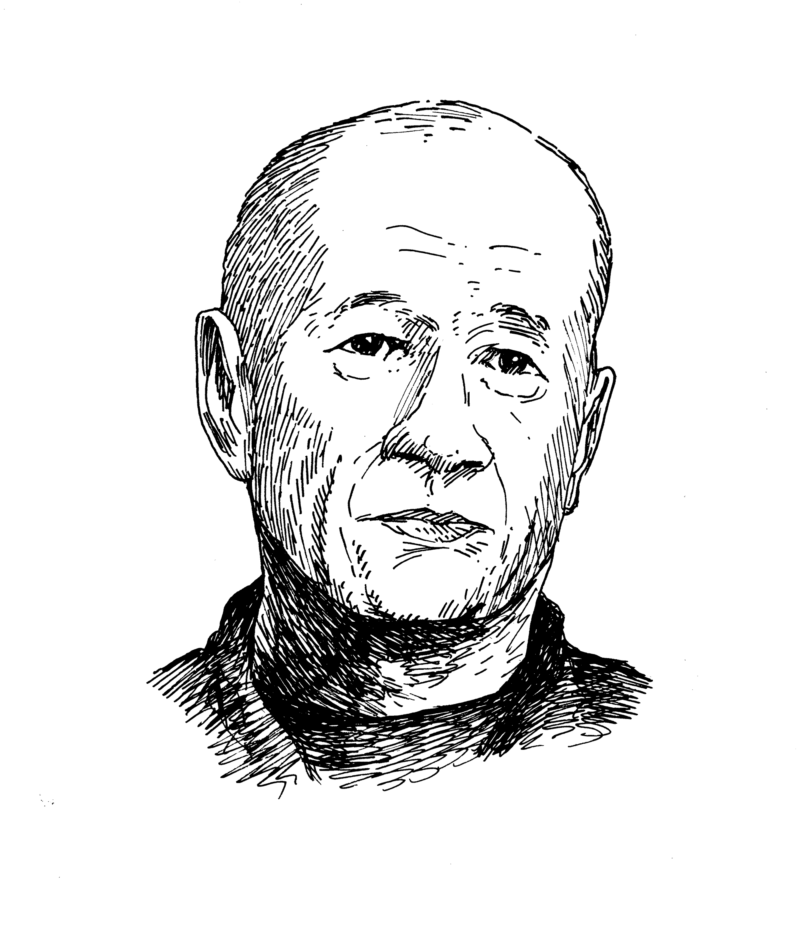

This interview took place in May 2018 at Hsieh’s sun-filled studio in Brooklyn, surrounded by shelves of archives of his artwork. At age sixty-seven, Hsieh moves quickly and decisively; several times during the interview he leaped to his feet to illustrate his points with drawings, documentation of his artworks, and a business card for his favorite Italian restaurant. After the interview he insisted on treating us to Taiwanese dumplings at the Market, the café and restaurant he now owns nearby. The interview was conducted mostly in English with occasional Mandarin, the latter translated by Anelise Chen.

—Lisa Chen and Eugene Lim

I. CUTTING OFF THE TOES

THE BELIEVER: Can you tell us about your early years in New York City?

TEHCHING HSIEH: I’ve been here since July 13, 1974—almost forty-three years. It was tough, because I was an illegal immigrant. I jumped ship. I was illegal until I was granted amnesty [under the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986].

BLVR: When you first arrived, what did you do? How did you live?

TH: At that time, I lived on 180th Street in Washington Heights. In the beginning, I was afraid of the police, because I was illegal. But when I was looking for a job, I had to take the subway, and I found some people who I could tell were illegal and asked them where I could find a job.

I was a dishwasher. I cleaned restaurants. You cannot wash dishes for more than a month, or your hands will be gone—they get damaged by dish detergent. Restaurants are busy, crazy. I worked thirteen hours a day, maybe got paid $1.50 an hour. I did this for four years.

It took me two years to find SoHo. I knew the world’s art center was in New York, but I didn’t know exactly where. One day, by accident, I found SoHo. I tried to go back. I tried to remember one building… Two years after I found SoHo, I found some Taiwanese artists. I recognized one of them in the street and got to know the Taiwanese art community here.

One of the artists owned a Chinese restaurant in SoHo. For two years I worked in that restaurant moving a hundred chairs on the tables every night, then cleaning and waxing the floor. By then, I was living in a loft in Tribeca, not making art, just thinking. I hadn’t made art in four years. I had to work at the job, and I had to get over culture shock. I was twenty-eight when I did my first one-year performance. So for four years, I really felt strongly that I was wasting time.

BLVR: You’ve said your first one-year performance, Cage Piece, is not autobiographical, but for years you were working hard in restaurants, a very difficult type of work.

TH: Art has to be from life. I cannot ask someone else to do my concept. I have to do it myself. When I say something, I am also saying the opposite. So when I say my work is not autobiographical, I am also saying that I put the hard part of my existence into it, even if it stays underground. It is still part of [the work]. When I say I’m working or I’m not working, you have to think both ways to make it complete. You can say I’m wasting time or that I’m working very hard.

BLVR: You’ve said, “Life is a life sentence.” Cage Piece is, on a literal level, an imprisonment.

TH: The Venice show is called Doing Time. In America, the expression means being in prison. But I mean “doing time” as in dealing with time.

My work is not meant to be a political statement about prison; it’s more general. Everybody has their own cage. My art is different from painting or sculpture. My art is doing time, so it’s not different from doing life or doing art, or doing time. No matter whether I stay in “art-time” or “life-time,” I am passing time.

BLVR: Let’s go back to Taiwan and your movement from painting to your action pieces. I’ve read you didn’t know the term conceptual art but you had heard the word happenings.

TH: I had heard the words conceptual art, but there was no context. But to me, it was enough to sense it. I didn’t finish high school. When I came here, I didn’t really read. I only just saw pictures. That was already enough for me.

In the beginning I liked to paint—at age seventeen, eighteen years old, that time, Van Gogh inspired me. That period of time, you know, was very important for me to grow, to learn. The work was not mature, but it was important.

Lisa, you went to Venice? So then you probably saw I had three early pieces from Taiwan exhibited there. This was the first time I used a camera. And because I did abstract painting at that time, I could already tell the workers in the street were doing great abstract painting. So I just took pictures of their work, and I called this piece Road Repair. [Hsieh shows a photo of street repair work that looks like tar drippings.] You can see, they do good work.

BLVR: How did you make the move from gesture to action? In 1973, in your first action piece, Jump Piece, you leaped from a second-story window, which caused you to break both ankles. In the ’60s and ’70s, the performance artist Chris Burden was part of a network of artists sharing ideas and work. But what’s impressive about your work is that you seem to have developed it in isolation.

TH: We live in a civilization and we all get information from civilization. It doesn’t matter if I am living in isolation. I already knew New York was the world’s art center. I came here: that means I already got the message. It’s not that different from Chris Burden and his community. I had to find my own way. I’m not good at being part of a system. I had to find my question and the answer myself. I had to do it in an isolated way. Isolation, being solitary, is very important to me.

BLVR: Does the conceptual matter?

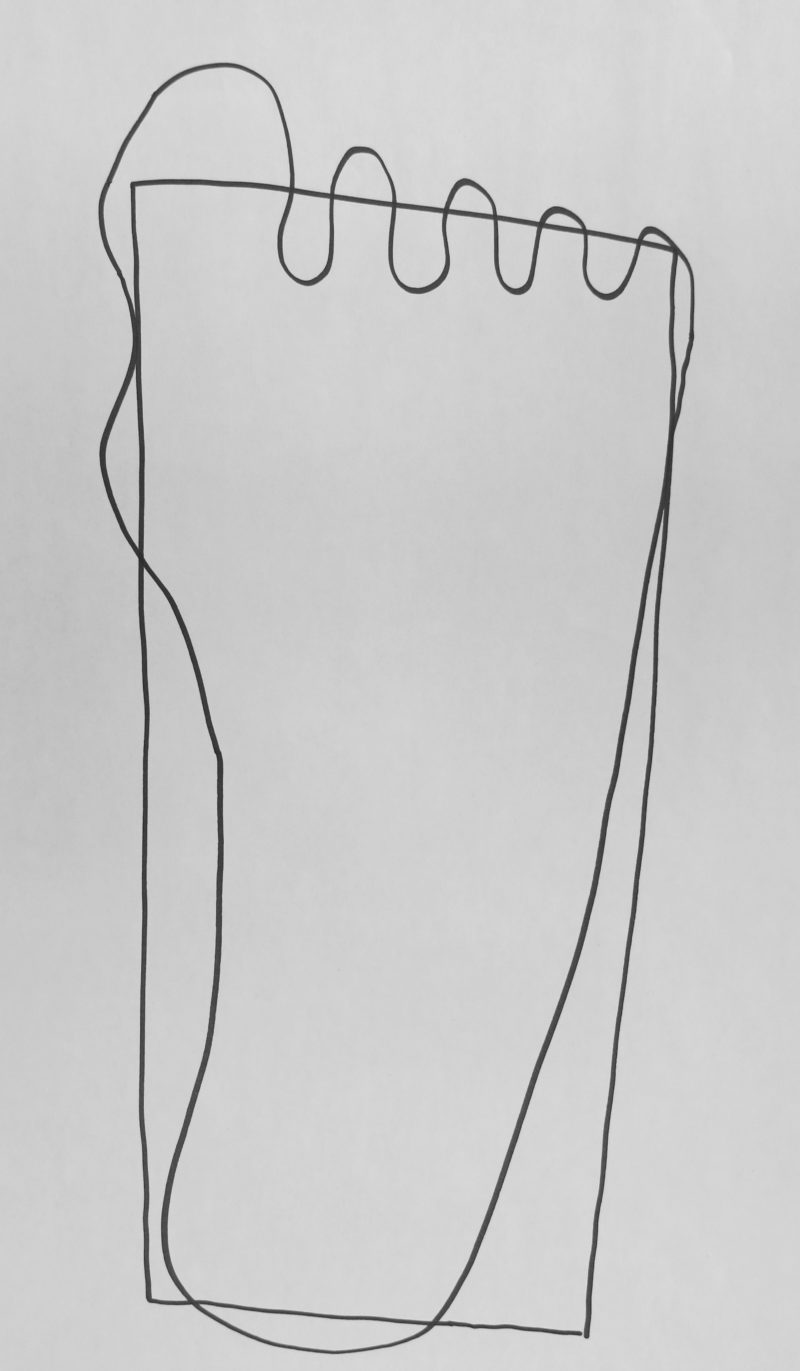

TH: My character is more like freethinking. The [label of conceptual art] cannot hold me. [Hsieh whips out a piece of paper and rapidly draws a picture of a foot. He draws a box around the foot, leaving the toes poking out of the box.]

Conceptual art is more like that… It cuts off the toes. The problem becomes that there is no foot, or human nature. They want it to be more square.

BLVR: Are there artists who come to mind who fall into this overdetermined conceptual framework?

TH: [Pauses] I have many words, but I cannot say that. Eugene, you have mentioned the conceptual a few times. I can see you feel strongly about that kind of foundation. [Laughter] You see words. I know that’s important, but if you care too much about that, you lose the natural quality. It’s not that my concept is not clear. I’m trying to give you the sense of my art; I’m not trying to give you the concept. Your questions are still trying to fit me into a concept. For example, if I punch the time clock 100 percent of the time, maybe you would say, Perfect! But I tell you, this would be like a machine. What is human about it? Being human is not about being Superman. It’s about understanding what’s nature. The rhythm. The rhythm of the universe. This is why science has a problem. If science can take over, then why do we need art? Because art takes care of some other part, some missing part.

II. “I KEPT MYSELF ALIVE”

BLVR: If Time Clock Piece had made a million dollars back in 1981, that would have been a problem. Because it would have meant you had become part of the system.

TH: If someone had offered to pay a million dollars to do [my work], people would wait in line to do it. But wasting time is my concept. When I punched the time clock, people said, “You don’t work,” but I was doing work. Being homeless is work. Homeless people are hungry and they have to eat, right? We all have to survive. If you’re alive, you work. So freethinking is work, you know what I mean? Your life, your heartbeat—that is all work to me.

BLVR: That’s why the statement you unveiled on the last day of Thirteen Year Plan said: “I kept myself alive.”

TH: I didn’t live on the street because I wanted to be homeless or to raise [awareness about] homelessness issues. I was just saying that we are no different. I work. Just because I don’t get paid means I don’t work? No, I’m still working.

As I said earlier, when I say one thing, you have to think the opposite; you can’t just follow what I say completely. In my work, I’m working very hard, but I’m doing nothing. I pass time, but I don’t do anything [except] wait for the next hour. But because I didn’t produce anything, society says, “You are wasting your time.” But if you pay someone a million dollars to do what I did, then society says, “You are doing a good job.”

BLVR: When you finished the year of Cage Piece, when you emerged from the cage, you’ve said that people looked like wolves. Could you explain this remark?

TH: It’s because I was so weak. So that even a nice little girl, for example, could seem so aggressive, like a wolf. This was because I was so weak. My body was so weak.

BLVR: Your comment then was about your own physical weakness? And it wasn’t a comment about human nature?

TH: Yes, at the time, but I’ll tell you that if you’re sensitive enough, you can see the animal nature in the human. When you watch, say, a National Geographic documentary about animals, if you’re conscious, you can see how even someone who is considered a very nice person is actually no different from an animal. We have many sides. We hide our nature. We try not to show our baser parts in public. If you bring them out in public, then chaos becomes an issue. It becomes a world without rules.

BLVR: You’re saying that secretly we are like animals. And that deep down we’re like violent animals who just want to live and eat and hunt.

TH: Right. And also like animals, we are overacting. And we eat too much.

BLVR: Did you say we “overact” or we “overeat”?

TH: Both ways! [Laughter] I mean that if you wish to stay innocent, you really cannot. It’s like that Christian phrase original sin. This is part of our instinct and strategy. Look, I’m not trying to be a holy man, OK? I see myself more as a criminal. That’s the way I approach things.

But in my criminality, maybe it’s best to add a word before criminal. I add one word—so I might be called a sincere criminal. I don’t mean 100 percent sincere. No one is 100 percent sincere. I’m what you might call a “sincere thief.” Let’s say human beings’ natural identity is that of a “thief.” My concept of an artist is that they are at a slightly higher level than a regular thief. An artist is a sincere thief… Of course, many artists are just regular thieves. [Laughter]

III. ROPE PIECE, TORCH PIECE, NO ART PIECE

BLVR: After Rope Piece, your next work was quite different. You then did No Art Piece. That was a radical change.

TH: All my work is repetition. This concept is very strong in my work… I don’t really have a new idea, but if you have nothing new, you have to ask, What can make a different angle? Cage Piece, and then Time Clock Piece—do you feel the repetition? People can answer in different ways. Some people will say, No difference! And then another person will say, Oh, it’s different! So it depends on what angle you want. All answers I give, afterward the person will respond: You answer by not answering. So that’s the way I talk about my work.

BLVR: Making art and then not making art are pretty radically different. But you’re saying they’re not very different. Did you ever worry about not producing? Marina Abramović called you a “master” and said that you’ve done important work, much more important than artists who have done many works.

TH: I only did six pieces. At the time of the last piece I was only thirty-six years old. I didn’t produce much art. Of course, some people will judge me for this. Marina is so nice to me. Did I want to continue from one year to the next even if I only had a bad idea? I’d rather not do it. People might say, Oh, you’re not very creative, but that’s OK.

BLVR: There’s a piece of yours we’ve read about that you abandoned that would have involved volunteers holding and passing a lit torch over the duration of a year, with you participating as a witness. Had you gone through with it, this piece—let’s call it Torch Piece—would have occurred right after Rope Piece. Can you talk about Torch Piece a little bit more and why you decided not to go through with it?

TH: That piece was supposed to be underground. I decided not to do the piece. It didn’t work. The concept was not clear enough for me. Also, I was having trouble finding people. I tested the concept out for one day. I found that I could not make it work. First I had to follow the person holding the lit torch. If you have the torch for three hours here and the next person lives in Manhattan, then you have to take a cab or walk, but it all has to continue for [the] twenty-four hours of the day. And also I had already designed the torch to have an alarm on it. If the person didn’t hold it when I was sleeping, the alarm would go off to wake me up.

BLVR: So conceptually it didn’t work because the logistics didn’t work?

TH: Not only that. It had to do with my personality. I’m not so good for social collaboration. I’m not a social person. Two people is enough for me, like Rope Piece. A hundred, a thousand, I feel my character doesn’t work in that kind of situation.

BLVR: That’s what we were thinking—that you recoiled because the move from two in Rope Piece to a more social endeavor in Torch Piece was too much.

TH: Also, my work between these two pieces, there’s a gap in time… OK, I’ll show you, and then you’ll know what’s going on. [Hsieh gets a chart of his planned retrospective that shows the amount of time between pieces.] OK, you see here, right? It says 361 days [between Rope Piece and No Art Piece]. I didn’t want the time between pieces, the “life-time,” to be bigger than one year. So my deadline had come, already came, time couldn’t stop, and I had no new idea, so then I just did no idea of passing time, so No Art Piece.

BLVR: You’re saying that you had the idea that the time between your pieces couldn’t be longer than a year. Did you have this idea from the very beginning, from when you did Cage Piece?

TH: I don’t publicize this idea, but that’s what I had wanted. I wanted to make a continuity. If the gap is too long, you lose the continuity. Of course, it’s impossible to finish one piece and then the next day begin another piece, but I didn’t want the gap to be longer than one year… Well, from Outdoor Piece, I was already thinking that.

IV. WHITE SAUCE AND ASIAN AMERICANS

BLVR: The rules for Thirteen Year Plan say, “I will make ART during this time. I will not show it PUBLICLY.” So our question is: what kind of art did you make?

TH: I’ll tell you about one piece that I did. It is called Disappearance, and it started in 1991. I tried to go to Alaska, but I only got to Washington State. I tried to leave society. Of course, I was not out of society; I stayed in society. But I was a stranger. Both Disappearance Piece and Cage Piece were [done] in isolation. Compared to Cage Piece, when I was in New York at my studio, I felt it was home even though I was isolated. Real isolation in Disappearance was double exile. I did it for half a year. I didn’t continue, because I felt the intention of doing “art for art’s sake” was heading toward death and hopelessness, so I gave up… In Cage Piece, I could still find a home. But in Disappearance I felt like I was back to 1974, just arriving in this country. That kind of feeling. It was very, very depressing, difficult.

BLVR: Wasn’t the time for Disappearance also very isolating? Wasn’t it just extremely lonely to live without connection, to live without friends?

TH: I know that word, lonely, but to me, in my work, I don’t really use the word lonely. Maybe I should, but I don’t use this word. Because, you see, when I was at the Venice show, then I felt this word. More than before.

BLVR: Were you lonely in Venice?

TH: I went there to do a job, to do the art show and to talk to people. But after that job, then I just went to my hotel and ate my dinner. I didn’t have an assistant. I was by myself. Probably that’s my life. My real-life existence is that way. Like in here [gestures to studio], I feel it less. But there, it was work, do the job, and then, after, you were on your own. But I enjoyed myself on my own. I enjoyed eating spaghetti. [Laughter] Every day I ate the same thing. I ate spaghetti with white clam sauce. That’s my favorite.

BLVR: [Incredulously]: White sauce?!

TH: Yeah, white sauce: it is called spaghetti alle vongole. Every day I ate that.

BLVR: Wait, in Venice? Or here in Brooklyn?

TH: Venice. But here too. I know one good Italian restaurant. But here’s what I’m trying to say: in Picasso’s early work he painted circus performers… Those kinds of people, they do their work, but, afterward, maybe they don’t have a wife, a family. They only have their isolation.

BLVR: You’re saying that after the performance, after the carnival and spectacle, the feeling the performer is left with is one of isolation and emptiness.

TH: Like a clown, you’ve made them laugh. And then you’re back home on your own. Then you feel lonely. But when I went to Seattle, when I did the Disappearance Piece, it was different. Then I think survival was more difficult than loneliness. I mean the difficult physical facts of survival, and these factors were stronger than any loneliness. I didn’t have much money and it wasn’t easy to find work.

BLVR: Speaking of isolation and art, there’s a famous conversation between you and Ai Weiwei and Xu Bing that was published in The Black Cover Book. What was your relationship with them and other expat artists? How did that conversation happen and how did you meet?

TH: Ai Weiwei was moving to New York and looking for a place. I think it was around 1983, at the time of Rope Piece. He became my tenant. I had a five-thousand-square-foot space, and I rented a studio space to him for a year or so. Around 1993 or ’94, he went back to China. I met Xu Bing in 1991 when Ai Weiwei and I went to see his solo exhibition at Madison University.

BLVR: So you all were friends. Did you feel a brotherhood, friendship?

TH: Yeah, we were and still are friends, although we are different. Isolation is a good word; it has become very important for me. I’m on my own. Until I can control my art, I need isolation to see things clearly. As a symbolic figure, Ai Weiwei has his own way of isolation. Like when you come to this country, you don’t know many people. You have no friends but you need help, right? I had a relative ask me: how can you make a friend here? I told him it’s simple: if you can help others, you can make friends; if you just ask for help, you don’t have friends.

BLVR: Everything is transactional.

TH: It’s that’s simple when you first arrive as an immigrant. In Taiwan, of course, there’s a natural order to relationships. You have your classmates, your relationships. It’s more natural to develop friendships. But I have a more isolated character. I’m more alone. I’m more comfortable that way, but you still need help sometimes.

In the beginning I couldn’t meet your kind of people. Your kind of people would say, “What is this guy, a stranger, an illegal?” Because your kind of people—this is the first time I’ve been interviewed by your kind of people in forty-two years.

BLVR: Really? Wait, what do you mean, our “kind of people”?

TH: Asian American. [Laughter] You get it! This is the first time. I’m not trying to make it an issue.

BLVR: You say this is the first time Asian Americans are interviewing you, which is both surprising and not, but you should know, for us, you are a very important precedent, a groundbreaker.

TH: I just wanted to say that it’s come late. Forty-two years late.

BLVR: In the past you’ve said your work is influenced by Dostoevsky, Kafka, and other artists. But you’ve also listed your mother. What was the influence she had on you as an artist?

TH: I was influenced by her dedication and sacrifice. My mother is Christian; she has her own faith in God. Because I am an atheist, I put my dedication and sacrifice into the art rather than God. Even though I wasn’t a filial son in childhood, I always acknowledged what I inherited from her. A priest may say things that sound good, but they may not be close to God, not like the pure worshipper. My mother has a pure, close-to-God way of believing and doing things, including how she deals with family and other people. And she has a strong will. In art, I use her way of doing things. It is not a public way. The priest is public. Art is public.

Maybe the examples I use instead are Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Dostoevsky knows human darkness. But he uses darkness to access the pure. Tolstoy is more about light and optimism. Dostoevsky to me feels more contemporary. He has a contemporary view of human existence. To me, my mother is more Tolstoy. But I’m more Dostoevsky. I do the dirty work.

But my dirty work is also pure. I’m pure in art, but I know dirtiness and I know evil. To show your art and to survive in the world, you must know a little bit about the dark side.