Adrian Tomine’s signing last March at Brooklyn comics shop Rocketship drew a legion of devoted readers. Eager fans admired the preliminary studies and black-and-white drawings for the latest installment of Optic Nerve while waiting to approach the bearded California-born cartoonist. Tomine was genial but observation revealed that his focus was rather determinedly directed at the task at hand: his precise, slightly ornamental rendering of fans’ names onto copies of the issue. The exacting style that characterizes recent issues of Tomine’s ongoing series entails a high level of absorption in his work, yet the social unease that distinguished his presence that evening is perhaps the most recognized feature of his stories.

At age twenty, Tomine signed on with Canadian comics publishers Drawn & Quarterly, and his talents were quickly recognized: The following year, Optic Nerve, which had begun as a self-published venture, was nominated for a Harvey Award for Best New Series, and Tomine himself won the Harvey for Best New Talent. Over the next decade, Tomine continued the series and published collections of it and his early work; he earned a degree in English from the University of California, Berkeley, and moved to New York; and his illustration work began appearing in the interiors and on the covers of magazines such as the New Yorker, Rolling Stone, and Esquire. It’s a fair bet that his new book, Shortcomings—which collects issues 9 through 11 of Optic Nerve and has already garnered praise from such literary luminaries as Jonathan Lethem and Charles McGrath—will only further secure his title as the “most masterful” and “most critically acclaimed” comics writer of his generation.

Tomine, however, shies away from such overheated designations, preferring instead to pay regard to the importance of other cartoonists, particularly his predecessors, writers like Peter Bagge, Julie Doucet, Dan Clowes, and the Hernandez Brothers. In this humble aspect, he couldn’t be more unlike Shortcomings’ hypercritical, sarcastic, and downright crabby protagonist, Ben Tanaka. Tomine’s Brooklyn apartment—as spare and unassuming as his stories—was an air-conditioned haven when I met with him on a hot day last June.

—Nicole Rudick

I. “IT’S COLD WATER IN THE FACE TO REALIZE YOU’RE NOT NEARLY

AS SPECIAL AND AS UNUSUAL AS YOU MIGHT HAVE THOUGHT WHEN YOU

WERE AN ALIENATED TEENAGER.”

THE BELIEVER: Drawn & Quarterly began publishing Optic Nerve in 1994, but had you self-published a few issues of it before then?

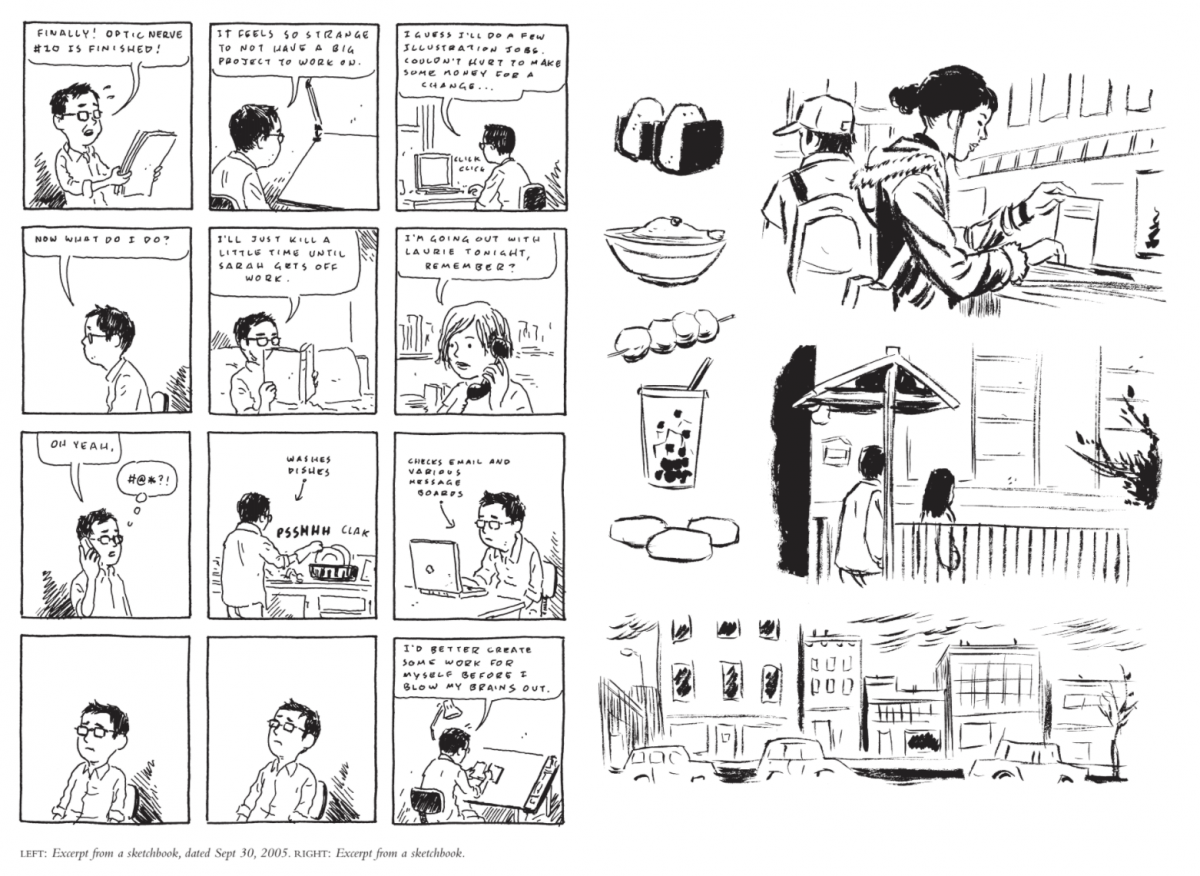

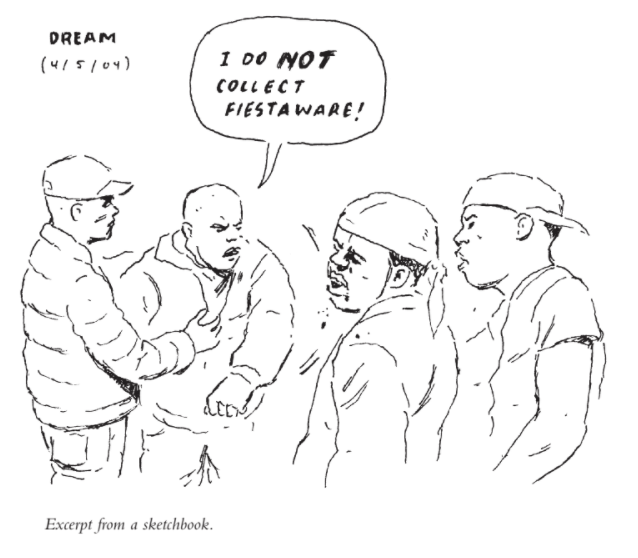

ADRIAN TOMINE: Yeah, I started when I was a sophomore or junior in high school, just making little Xeroxed pamphlets. Those minicomics were the most intensive training ground that I had, the biggest leaps of my evolution in figuring out how to do what I was trying to do—all the rehearsal work before the performance.

BLVR: What sort of relationship did you have with the older generation of writers when you were starting out?

AT: Through strange circumstances, I’ve ended up becoming really good friends with a lot of the people who were my role models when I was younger, so I have this really amazing opportunity to pick up the phone and ask someone, “You know, I don’t really feel like I know how to do this, can you explain it to me?” The early ’90s was a very D.I.Y. era, and there was more of an interest in zines and self-published comics, so people would mail their zines to someone who was working for Fantagraphics or Drawn & Quarterly. In my case, I got little write-ups from Peter Bagge, Chester Brown, and a few other people who plugged it in their comics and recommended it. When I entered the world of comics more completely, we would cross paths in person.

BLVR: Did you get any advice early on that fundamentally shaped your comics?

AT: Oh, yeah. One of the by-products of being allowed to start my professional career prematurely is that the evolution of my work is really evident. It’s not like readers come upon my work and say, “Well, you’re fully formed, you’ve got your own thing, go for it.” When people see me struggling on paper, I think it invites an almost collaborative relationship with the outside world, and that includes readers and other artists.

BLVR: Do you mean fully formed as an artist?

AT: Yeah. Someone like Julie Doucet was as great with the first thing she published as with the last thing she published, and it was completely her own style with no clear antecedents. It would require one to be quite an asshole to tell her how she could improve or what she might need to focus on. With me, people saw me struggling with different ideas, different methods. So I got a lot of advice, some solicited, some not, and that continues today. But in terms of the really valuable advice, I learned a lot of concrete stuff by seeking it out. Once I felt comfortable enough around some of the people who had been heroes to me, like Jaime Hernandez, Dan Clowes, or Peter Bagge, and I had gotten over that intimidation, I would seize on these opportunities to ask, “In this issue, you did this thing, and how did you do that?” Without fail, every cartoonist that I asked advice from bent over backward to be helpful and encouraging. It took many forms: some of it was just an implicit acceptance, like being invited along to the dinner with all of the good cartoonists, or sitting down at a drafting table with an artist and him showing me how to draw backgrounds and perspectives.

BLVR: When you mention being fully formed as an artist, or not being fully formed as an artist, many readers and critics commented early in your career about your being the voice of your generation, and they really argued over the application of this label. There’s something so funny about it, because at the time, you were quite young and yet already you’re being characterized in a very profound way.

AT: The first time it came up, I was doing a talk at a bookstore, and the woman from the store introduced me using that phrase, and I remember just feeling like, Oh, now I’m really in trouble. To me, any amount of flattery that might have come from it was totally overpowered with the thought that, Hey, I’m not appointing myself that, but people are going to think that I am.

I’ve never been the one to make those kinds of pronouncements. Seems like every time I come out with some new thing I just get inundated with very polarized responses—“It’s the best,” or “You suck, give it up”—just really extreme responses. I think that a lot of it has to do with what people other than me are saying my stories are. If someone says, “He’s the voice of Gen X,” or whatever the accolade is, that really sets up something for people to contest and tear down. I’ve tried to discourage a lot of that. I dislike having unfair praise heaped upon my work, because I know what the response will be. It’s been surprising to me because one of the weird things about working publicly—I’m not doing these stories and putting them in a drawer; for some reason I want these to go out into the world—one of the strange by-products of that is that it makes you evaluate your relationship to the world. Prior to publishing my stories, I felt like, I’m really weird, I’m really different, I’m an outsider, I can’t relate to people and that’s why I draw comics. In my mind, I was flattering myself, I was thinking, I love the way Robert Crumb tells stories that are so imbued with his weird personality, celebrating his distance from mainstream culture. Then suddenly I start getting letters that say, “I know exactly what you’re talking about, I relate to you, you’re speaking to me.” On one hand, it’s nice, but at the same time, it’s cold water in the face to realize you’re not nearly as special and as unusual as you might have thought when you were an alienated teenager.

BLVR: Your first collection—32 Stories—was released in 1997. It was followed by Sleepwalk in 1998, which gathered the first four issues of Optic Nerve and contained sixteen short tales. Summer Blonde, the next collection, comprised four stories. Shortcomings, however, brings together three issues and is a single story arc. Have you been consciously working toward longer stories, or did it develop simply as a function of your maturity as a writer and artist?

AT: With Shortcomings it was more of a conscious effort to stretch than something that felt natural. Between Sleepwalk and Summer Blonde it was a natural evolution, where I was feeling like I wanted to try something that was twenty pages long and just plowing forth. To me, there was certainly not an easy, natural progression between Summer Blonde and Shortcomings. There was probably some amount of me saying, “I want to throw myself into deeper waters and see what happens.” It’s been an ambition of mine since day one. I’ve always been really impressed with some of the longer graphic novels and thought it would be really amazing if one day I could try something like that. I think I was nudging myself a little bit more than I was comfortable with.

BLVR: What was most difficult in the transition?

AT: As a lot of my critics will tell you, I’ve never written plots before. The idea that I would need to have some structure and some sort of causal relationship between vignettes that normally would have stood on their own—that was a challenge. I expected that, though. The unexpected challenge became the endurance and tenacity that’s required of drawing a longer story, especially in the style that I have chosen. At about the halfway point, I suddenly had this great understanding of why certain artists draw the way they do.

BLVR: How long did it take?

AT: Five years. Which is kind of horrifying to say out loud. I’m looking at the book and it’s very small. It’s not a very big book. In a way, even when I was doing something as long as twenty pages, I almost had the brainpower to lay out the entire story in my head, so I knew what each page was going to be like, down to the last panel. Shortcomings was beyond my brainpower, so some of it had to be worked out as I went, and some had to be problem-solved as I moved through it. It’s psychologically a weird experience to be so aware of the fact that the real time of your life is moving much faster than the fictional time you’re trying to depict. You start to feel very weighted down sometimes.

BLVR: Do you think you’ll aim for the long form again?

AT: The thing I’m working on now is a short story. I agreed to do it for an anthology when I was working on Shortcomings, so it was the first thing I dove into after I finished the book. It’s really fun for me. It’s the most fun I’ve had at the drawing board in a long time, to have it very contained and to feel like I can draw it differently and can use different materials and can work at a different scale. Once I drew the first page of Shortcomings, I was locked into a whole system for the next hundred pages. I guess I’m just going to have to see how things go. On one hand, there’s a part of me that feels that this was still some kind of a warm-up, and now I want to do something even bigger and more time consuming. On the other hand, I had this feeling like maybe a lot of us right now are trying to force comics into being something that it might not be designed for.

BLVR: In what way?

AT: That partially due to the world of media and commerce, the idea of a comic book has been lost in the ghetto, whereas the graphic novel is now being held up as something to aspire to and as something that’s respectable for adults to read. The idea of asking one person to do every step of the process and to do something that’s both written and drawn, and in a lot of cases colored, and then expect that to come out with a frequency and with the physical heft and impact of a prose novel, might be asking a bit much. There are certain people who are absolutely suited for it. There’s no doubt about the success of Maus or Jimmy Corrigan. I think Chris Ware is really, really suited to it. He can work relatively quickly and efficiently, and I think he does an amazing job of making… he’s very much a cartoonist. The expression of everything is not separate parts, it’s one thing, it’s the words, the pictures and colors and everything, all coming at you at once.

BLVR: Do you think the lag time between producing this length of book for you isn’t suited to the demands of book publishing today?

AT: I was talking to someone who recently had pretty big success with a graphic novel, and it took her seven years to produce it, and now the publisher is ready for the follow-up. And that’s daunting. I don’t know if a lot of the new readers that we’re acquiring at bookstores are necessarily going to still be as enthusiastic about us ten years after we get written up in the New York Times. And also I just think that there are some people who are absolutely suited to it and enjoy the process and produce great work. At the same time, I talk to other cartoonists who are committed to some long-term project that’s going to take them ten years, and that feeling of being right in the middle of it and not feeling like you’re anywhere close to the finish—it’s a lot to take on, and I know from my experience that when I start to have that feeling of not working fast enough or not making enough progress, I start to become really obsessed. My real life starts to suffer. I start shutting out the real world to achieve more with each workday, and I have this feeling almost of panic, of needing to produce.

BLVR: Do you generally enjoy the process?

AT: [Laughs] It’s not pure joy, that’s for sure. In the scope of what I could be doing to make a living, I enjoy it a lot. On a minute-to-minute basis, there’s a lot of frustration. I guess there’s just a part of me that’s not very enthusiastic about finding myself ten years from now halfway through a story that may or may not be any good. I also am trying to think—and I hope other people will start to see it this way—that sometimes a comic can be a great thing because it’s a comic, not because it’s almost as good as a movie, or as good as a prose novel, which I think is the way a lot of people are now trying to process it. The experience of reading a comic should not be the time it takes to turn each page. It should be like other visual art that you can go back and look at and see in new ways. You start to get nervous when the value of a comic book or graphic novel is relative to the achievements of some other medium.

II. “WE’RE GETTING TO THE POINT WHERE

IF SOMETHING IS A LITTLE INCONCLUSIVE,

IT’S CARVERESQUE.”

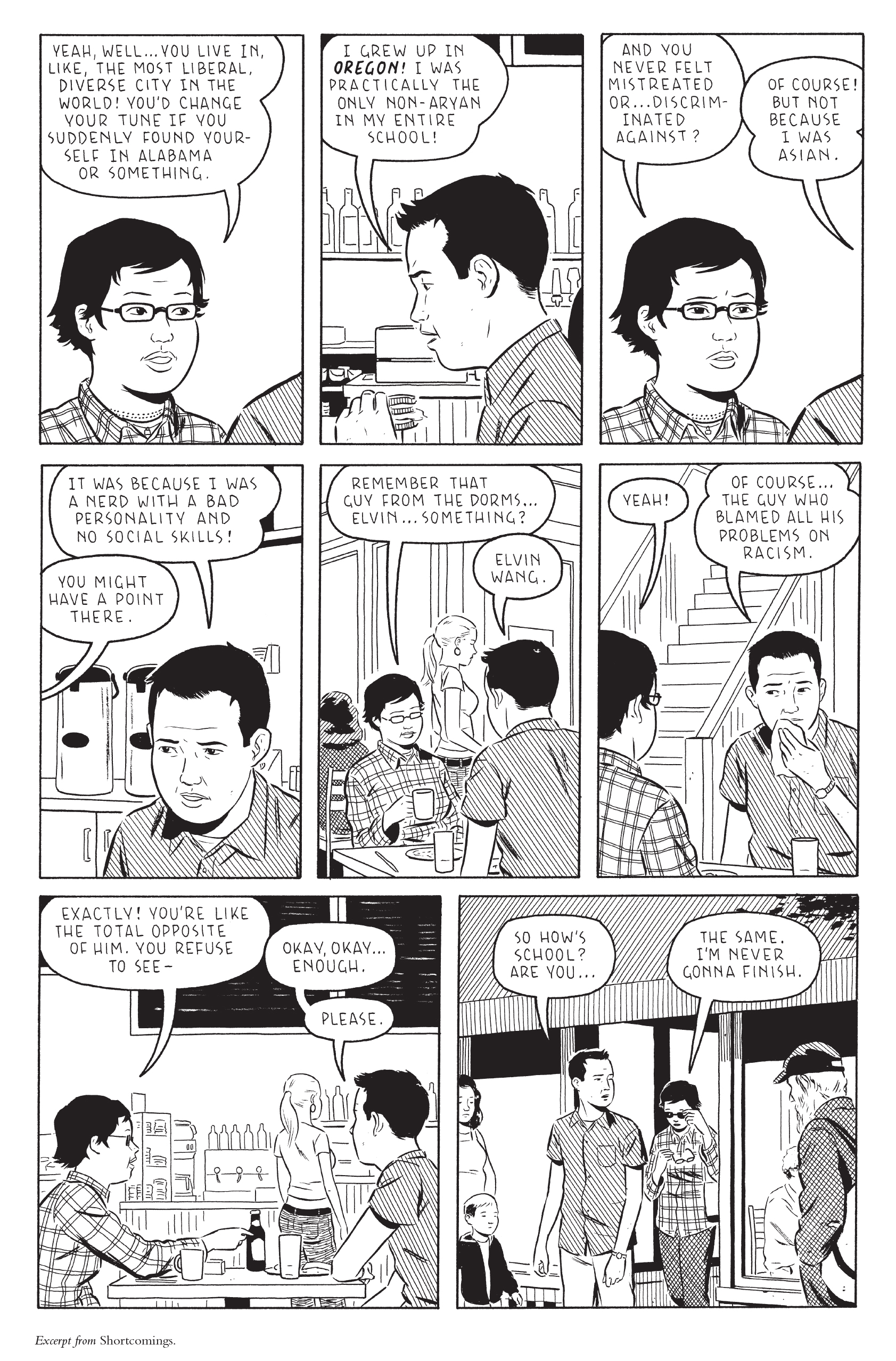

BLVR: When you drew yourself in earlier issues, you seemed to disguise your ethnicity. And here you’re dealing head on with issues of race and racial stereotypes.

AT: I certainly wasn’t consciously hiding my identity in the earlier work, though a lot of people have brought up the fact that I drew myself without eyeballs. I think there was a point in the past when I felt that my options as an artist were either to make race a nonissue and deny its impact on life and just say, “Don’t think of me as an Asian cartoonist. Just think of me as a cartoonist.” Or the only alternative in my mind was to be like some politically active guy carrying big placards, making giant pronouncements about political issues and injustice. In my ignorance, I chose the former because I didn’t want to do the latter. At a certain point, I realized that it’s not some binary set of options. There’s a lot of area in between to be mined. And so that was what led me into this book.

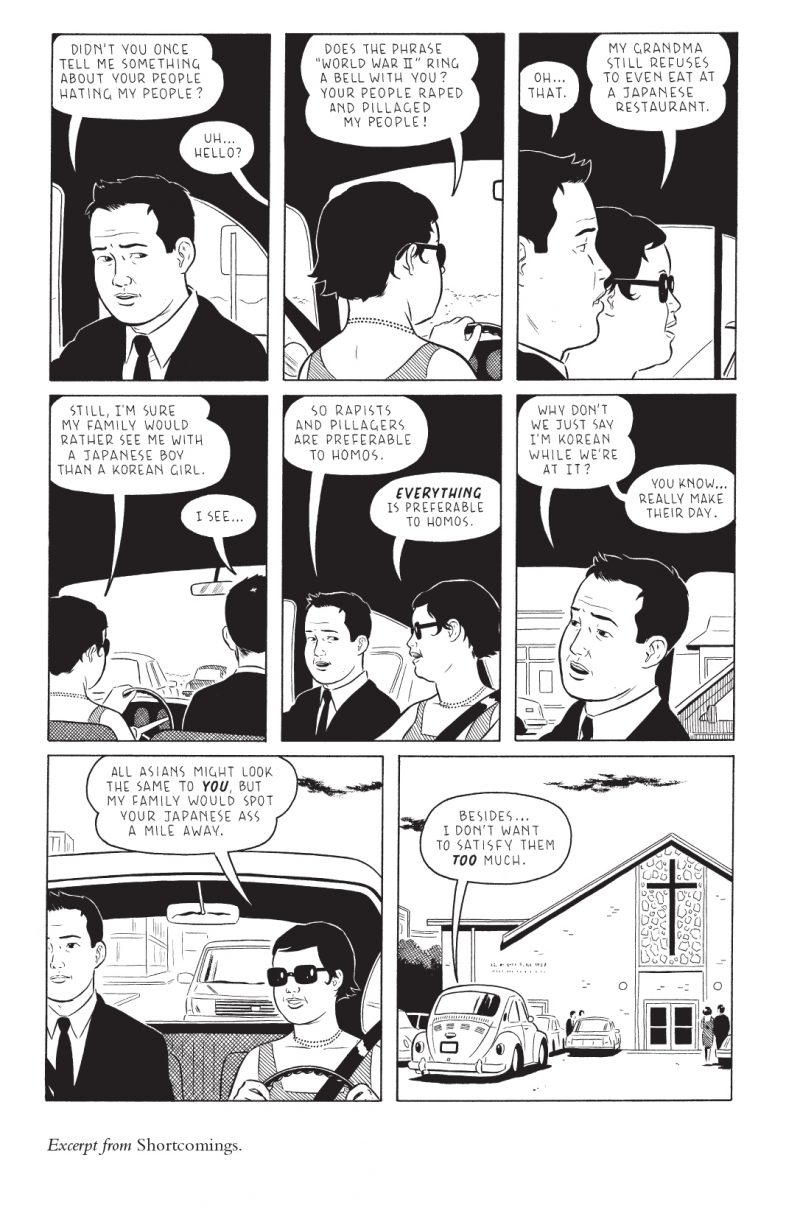

BLVR: It’s quite a complex examination of stereotypes, because it’s not as easy as, say, a guy getting attacked on the street because he’s Asian American. Rather, it’s Ben who entertains perceived stereotypes about himself.

AT: There were a lot of suggestions over the years to do a story that would somehow address race, especially when I would do interviews with Asian American publications. I think when I finally got it in my head that I was going to do the story, I wanted to avoid doing what I thought people wanted me to do. There were certainly some people who wanted me to do a feel-good story that affirmed a lot of very commonly held beliefs. Especially for younger readers, maybe that’s a good angle to take. In general, it didn’t appeal to me. I wanted to not shy away from some of the more racy topics that might go along with that. I wanted to try to create characters that happen to be Asian but who are pretty different from those we generally see in our culture, in our commercial culture.

BLVR: Have you already received criticism for the book?

AT: Oh, yeah, from the beginning. Since it was published in serial form, I’ve been getting responses over the past few years, as it’s come out. There’s been a fair amount of negative response to it from Asians.

BLVR: How do Asians find it offensive?

AT: There are people who object to the portrayal of Ben—not that my portrayal of him is racist, but that I’m depicting him as occasionally saying things that could be construed as racist. For some people, that’s hard to see. There are some people who are saying, “We’re trying to get the world to stop treating us in a racist way. What the hell are you thinking by showing one of us saying things that are just as bad?”

BLVR: But Ben is very much struggling with his own identity by working through these stereotypes. And some of the comments simply poke fun, like when Alice, who’s Korean, says to Ben, “All Asians look the same to you.”

AT: I might be alone in this, but I love hearing people who come from different backgrounds than me addressing things head on and saying, “There’s this stereotype about us and it’s partially true and partially not and here’s how it’s affected me.” That interests me. Whenever I’m around someone in a social setting, who can intelligently and humorously address some of those things about themselves, I want to hear about their experiences. Some of the other criticisms that have come up have been about… to be blunt about it, there’s a recurring joke about the small-penis stereotype, which runs through the story, and I think there are a lot of people who think that even though I’m doing riffs on it, that its very acknowledgment in the text is a real disappointment and is hurtful. I can understand how it would start to feel like “Even if you’re just trying to be smart about it, don’t even bring it up. We’ve had enough of that.”

BLVR: The realism in your stories has brought comparisons to Raymond Carver, who also dealt in tales of ordinary people, the marginalized and desperate. It’s not surprising, too, that you’re involved with Yoshihiro Tatsumi, whose work you’ve helped introduce to U.S. audiences. You share with him a penchant for the downtrodden and their everyday tragedies.

AT: Carver’s stories are more austere and subtle than my stories, and, on the other end of the spectrum of realism, Tatsumi is more dramatic and daring. He goes big sometimes. Those are both artists that I’ve enjoyed.

BLVR: Did you see a bit of your own work in Tatsumi’s? Is that where the original appeal lay?

AF: I actually was first exposed to Tatsumi’s work when I was really young, when I started drawing comics. There was a bootleg English edition of his work that came out in the ’80s. Now that the editions that I’ve edited for Drawn & Quarterly are coming out, people are saying, “Oh I see why he liked it, because it reminded him of his own work.” Almost like it’s some kind of narcissism on my part. But the truth is, it’s the opposite, which is that I think my work was formed by being exposed to his at an early point. A lot of the kinship that people notice is not coincidental. I was very impressionable and trying to find my role models when I was twelve or thirteen. By circumstance, for the next ten years or so, his work was not very well known in America.

Carver and Tatsumi get brought up a lot in trying to find comparisons for my work, and sometimes it makes me apprehensive, especially with Carver because he’s such a great writer and so well known in that he’s entering that zone where the general public uses him almost incorrectly as being emblematic of a very particular way of writing. For instance, if something’s a little weird, it’s Kafkaesque. We’re getting to the point where if something is a little inconclusive, it’s Carveresque. It frustrated me, especially early on, when I was fumbling around in the dark with my work and I didn’t know what I was doing and I was ashamed of it the minute it was published. Then some journalist says it’s like Raymond Carver, and I have these horrible visions of some Raymond Carver fan seeking out my work and thinking, Oh my God, what are they talking about! [Laughs] When I was talking to another interviewer about the inspiration for this story, it was surprising to me that a lot of the stuff that, at least subconsciously, influenced me as I was working on it, in terms of other authors, was more like middle-aged Jewish men. People want to find connections to other Asian artists because that’s the subject matter here, but I didn’t sit down and read all the Asian American authors I could find to get prepped for this.

III. BIG, STUPID SOUND EFFECTS AND MOTION LINES

BLVR: In mainstream publishing, there isn’t yet a full appreciation of comics as a medium.

AT: At least in America. Right now we’re really in the middle of a big change in terms of where comics stand in our culture, and it’s like ripples going out in all directions in terms of how it affects us—the artists, the publishers, the business of it. Underground and alternative comics existed in a vacuum for years, where money really wasn’t an issue. No one would get into doing a black-and-white comic because they thought it might be a route to riches. If anything, it was a sacrifice, a financial sacrifice, to say, “Oh, I’m not going to do something more lucrative, and I’m going to sit down at the drawing board.” And now, there are big publishers offering advances, and there are royalties to be had.

BLVR: Your drawing style has become very precise, particularly in this book, but also over time. Is that a deliberate move on your part, or is it a mark of your improvement as an artist?

AT: It’s important to make a distinction between becoming more precise and becoming better. There are some people who may not like precision in their art. They may like it to be grittier and more gestural, more of a direct expression in the way that a painter would put his strokes on canvas. I wouldn’t want to just come out and say that I’ve gotten better. I think it evolved naturally for me. It was some personal taste of mine that guided how I worked, how I evolved. I think also the visual style evolved to suit certain ambitions I had in terms of the overall effect of the comic. Especially for this story, I wanted to really make it clear where everything was taking place. I want the reader to have a sense of the world they’re walking around in. Maybe if someone is from Berkeley they’ll recognize a lot of these locations and get the exact idea of where the story is supposed to be happening. Some of the New York stuff might be the same way. Short of just putting a caption saying, “Now they’re going to Juan’s Place, the Mexican restaurant in Berkeley,” you have to draw it pretty accurately to convey something like that, and that idea carried through in terms of facial expressions and gestures.

I set myself up for a lot of trouble by wanting to tell a story that is fairly earnest and emotional and expressive, but to do it in the most subtle, realistic way. Instead of someone getting mad and having steam fly out of their ears, just having the arch of an eyebrow. You run the risk of that being completely lost on the reader. That requires a lot of precision. I certainly don’t recommend this as a way of working for everyone, and I don’t think it’s a one-way path that I’m on, where my art is going to continue to be refined and made more microscopically detailed and precise. I also love doing the opposite. The story I’m working on now has big, stupid sound effects and motion lines. And that’s really a blast for me right now to be doing that.

BLVR: In some comics, there’s a disconnect between the narrative and the image, and you wonder what work the drawings are doing. In those cases, the art seems more illustrative. With Shortcomings, however, the images and words are so tightly woven.

AT: I think that disconnect… I think you’re right on with that. The smarter cartoonists are exploring that. They’re using it as an effect rather than trying to overcome it. They’re trying to say, “What does this offer me in terms of trying to tell a story with an unreliable narrator?” or something like that. With Shortcomings, when I started out on it, I wanted to make it as—this is the simplest way of putting it—I wanted it to be as readable as possible. I had the ambition of reaching a broader audience than I had before. I was very aware of the fact that there are a lot of comics out there that I love, because I’ve grown up my whole life reading comics and I know every little nuance of the language and all the implications. But for some new reader off the street who might be picking Shortcomings up as their first graphic novel, it could be very confusing, simply in terms of the mechanics of the storytelling, and I wanted all the responsibility to rest on the content of the story. I tried to make the visual style almost invisible.

BLVR: Most of your stories remain open-ended, and there’s never a problem with over-explanation.

AT: I think if anything this story might have the problem of under-explanation. Some of the responses I’ve gotten have taken the story very much at face value… I get the impression from some people that unless they get direct access to characters’ thoughts and realizations, either through thought balloons or narrations or some sort of showy action, then those thoughts and realizations never existed. Some of the story hinges on believing in the reality of it, that if someone is sitting silently in a chair, they’re not just sitting there completely brain-dead, that there is stuff happening internally that we as the observer don’t have access to.

BLVR: From the first issues of Optic Nerve to Shortcomings, your characters have developed from crank-calling loners and high-school dorks into adults—albeit dysfunctional and cynical ones—who no longer seem to hold outsider status. Is it that the categories that define us when we’re young become more rarefied as we grow up, so that geeks, losers, and loners who are marginalized as kids find greater acceptance in adult culture? The twentysomethings of Shortcomings seem able to negotiate society with a bit more dignity and humor. Some of them are able to make the connections that characters in earlier issues are unable to make.

AT: I take that as a real compliment, because I was trying to write a more adult story. I didn’t want the conflict to be between the nerds and the jocks who bully them. I was hoping that this would exist in a world where that kind of stuff doesn’t even really enter into your mind. It’s not on my mind anymore. I don’t see the world in the same sort of strata as I did fifteen years ago. I sense a real difference in my work from the time I was younger and single and more involved in the world of music and going out to bars and all that. There were points at which I was trying to use my art to reflect positively on myself, to almost be flirtatious through the work. Of course the idea of someone trying to be flirtatious through a comic book shows you how flawed my reasoning was to begin with. Especially when I was in college, I had entertained some fantasy of meeting a girl because she liked my comics, and I was sadly kind of aware of that as I was creating the work and maybe censoring certain aspects or thinking, But I have to make it clear that that person is bad.

There are certain artists and filmmakers who, I get the impression, are trying to show off how bad their characters can be, how immoral their characters can be. But at the same time you get the sense that there’s a godlike presence condemning them a little bit, saying, “See these men? They’re so sexist and racist. But not me. I’m criticizing them.” I’m getting to a point in my life where my whole attitude about the relationship between myself and the audience is totally different. It’s really freed me up in a lot of ways. This is certainly not a story I would have written ten years ago, because I’d be really nervous about how it would reflect on me. Especially for people of our generation, who really celebrated certain attitudes—the outsider, the loner—it can have a real impact on the art when they realize, I have friends, I’m married, or I have kids. That’s certainly happened to me.