Agnès Varda is sitting in a hotel room during the Toronto International Film Festival, and there is a photographer looming in the corner. She doesn’t want him to shoot while she is talking—she insists he do it now. “Don’t take pictures of the others, please! Make no mistake which one is me,” she says. “We have a brunette, here. A blond. You have the choice. Oh my god. Move back!” she cries. “You have a telephoto! Why do you need to be so close? It’s like a gun!”

Six journalists sit around, drinking tea and coffee, all poised to interview her at once. She asks a newspaperman, “Did you get the press kit? It is full of information. You could even invent that you met me. Say, ‘We were in a little room. She had the light behind her because her eyes fear the light. And we had tea and coffee.’”

This interview is invented; many of the questions are made up. Of the questions that are asked here, I did not ask them all, but the answers are always Varda’s own. She was not interested in speaking to each reporter individually, and since her latest films, in particular, are more interested in the feeling of truth than the truth, there is no reason for me to argue with her method. I hope this interview conveys at least the feeling of the truth of speaking with Agnès Varda, if not the literal truth of the situation.

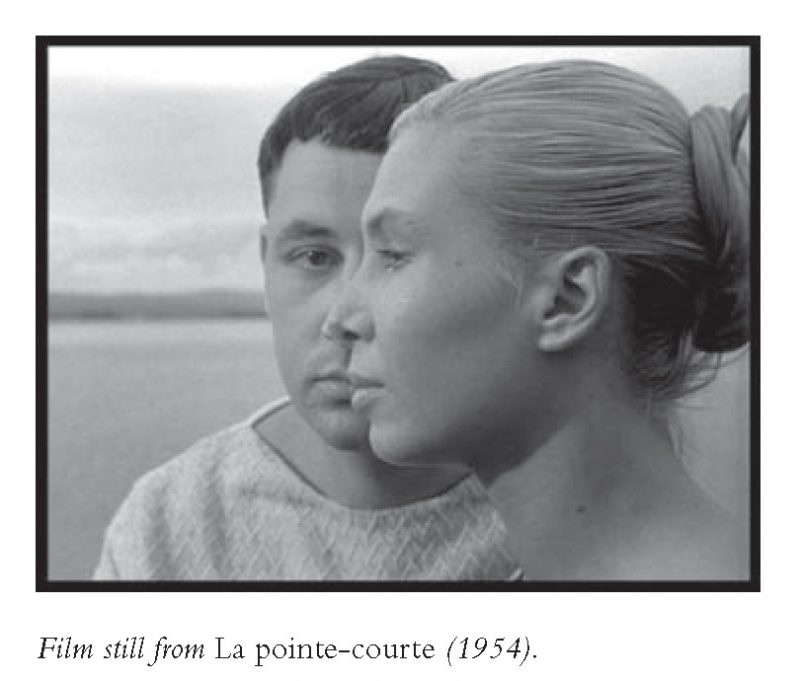

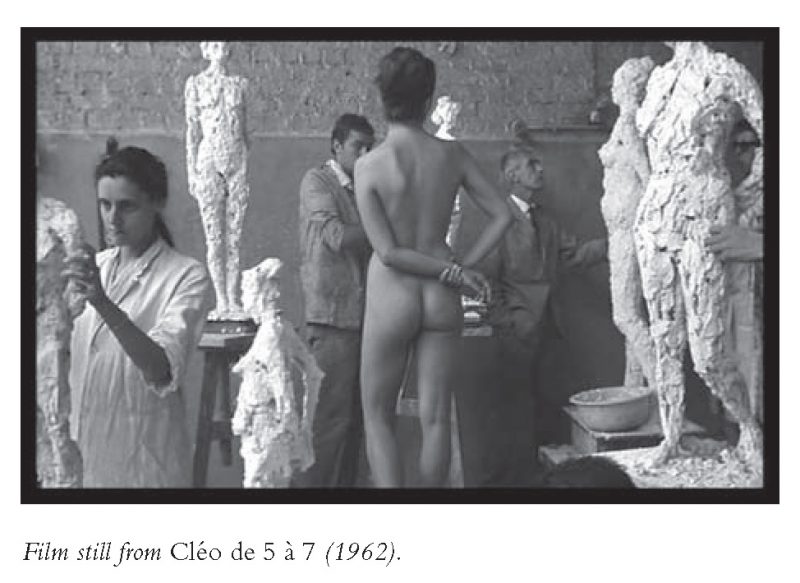

In 1954, Varda established herself as a significant figure in French cinema with her first film, La pointe-courte, only partly because it had come from a woman in her mid-twenties with no film training. It melded documentary footage of fishers in a fishing village with a somewhat melodramatic fictional love story about two young city-dwellers for whom the fishing village is mere setting. It is considered the first film of the nouvelle vague, and was followed by the magnificent allegory of beauty and death Cléo de 5 à 7 (1962). Recently, her four most beloved films were collected in a Criterion box set that shows her mastery, her sensitivity, her imagination and range. These include La pointe-courte, Cléo de 5 à 7, Le bonheur (1965), and Sans toit ni loi (1985).

Her most recent film, Les plages d’Agnès, is a collage self-portrait of her passions through eighty years of life, the material for which includes her past films, images from art, footage with friends, some invention, some fact. Her films have, from the beginning, encompassed many genres and none.

—Sheila Heti

I. “YOU HAVE TO BE STRONG TO BE A CARPENTER, MAYBE, BUT THE DIRECTOR OF A FILM DOESN’T NEED TO HAVE MUSCLES. THIS IS WHY I DIDN’T KNOW WHY I COULDN’T DO IT.”

AGNÈS VARDA: I should say nothing! I’m through with it! I hate to repeat myself all the time. I cannot invent totally. I cannot say something different to one person and then another. I cannot make it totally different each time, you know. I say so much in the film and so much even in the press kit! I quoted Montaigne. So I would say, can we have subsidiary questions, or side questions? Can we speak about the weather? Or the tennis that I watch in my room?

THE BELIEVER: It’s so nice to see that you have had the same haircut always, because I’ve had the same haircut all my life, and I always try to change it but it’ll never change.

AV: I remember when I tried it. I was nineteen and I put a bowl on and I said, Cut around! Because it was not the fashion at the time when I did that hairdo—and I kept it all my life! At the time of Cléo I grew it a little more, and when Jacques died I grew a bit here. [She pulls out a strand.] I made a braid because Chinese old people, they say that the God will take you by the hair to join you with—but God didn’t take me, so I cut the braid. Now it’s the same hairdo but it has two colors—come on! It’s different! It’s like an ice cream of chocolate and vanilla! I tried a wig. I hated myself totally white. So now I cheat. It’s my white hair, and I put color there. My grandson says I’m punk. I tell you—better they laugh about their grandmother than think she’s a bore. Some grandmothers are really boring! They ask, Ah ha ha—did you do this?—be careful—put your sweater on! C’est ça. So, in a way, we try to please them somehow.

BLVR: You had a remarkable career in an age when women didn’t have careers—

AV: I had a world. I don’t think I had a career. I made films.

BLVR: Yes, it would be odd, thinking of cinema as an extension of life as you do, and at the same time thinking of it as a career or trying to make a place in history.

AV: I don’t try to make a place in history at all! People put me in the history of cinema because my first film, La pointe-courte, was so ahead of some other filmmakers. Many filmmakers have made resurgent work, and I was just a little ahead of the time. It happened because of La pointe-courte, which is a very strange film, but very daring for ’54.

BLVR: How did you get started?

AV: I was a photographer first. I went alone to China—not alone, I was in a group, but I worked alone. I did it my way as much as I could. I have been sort of courageous about doing things, because I didn’t think I should do less than my brothers. But I wouldn’t be courageous in terms of a physical thing. I never fought, I never learned kung fu or boxing, I never went into these sportif competitions. I wouldn’t cross the ocean. I think it’s ridiculous to take such risk. But look, people love to do that. But I was not afraid of doing things I wished to do. I did not think that woman would be restrained. I never saw that, especially not in filmmaking, where you don’t have to be strong. You have to be strong to be a carpenter, maybe, but the director of a film doesn’t need to have muscles. This is why I didn’t know why I couldn’t do it.

When I started my first film, there were three women directors in France. Their films were OK, but I was different. It’s like when you start to jump and you put the pole very high—you have to jump very high. I thought, I have to use cinema as a language.

When I saw what painting had done in the last thirty years, what literature had done—people like Joyce and Virginia Woolf, Faulkner and Hemingway—in France we have Nathalie Sarraute—and paintings became so strongly contemporary while cinema was just following the path of theater. Theater! I mean, psychology and drama and dialogue and making sense! At that time, when I started, in the ’50s, cinema was very classical in its aims, and I thought, I have to do something which relates with my time, and in my time, we make things differently.

BLVR: Differently in what way?

AV: When I did Cléo, I thought, I have to work with time. We feel time differently when we are suffering or are in pain or we are waiting for something. So subjective time became the subject for me—plus the duration of the time of the film that the spectator perceives. I worked with matters that are there for any artist to work with, but which I worked at with cinema.

I didn’t have a list of things I should do this year, next year, find a good novel, sign two stars and make a deal—because I think cinema should come from cinema. I never adapted anything. Beautiful books are beautiful books, that’s it. I don’t know why we should transform them. I have respect for literature. If he found the words, if she found the words—this is a book! Bien! I didn’t think I should do a career by picking this or that. I waited for each film to become important for me. If I had no ideas for a film, I didn’t do a film. So I made not that many films for fifty-four years of working. I think I did fifteen long features and fifteen documentaries, or something like this, which is very little when you think of people making a film every year. Some people have done fifty or sixty films.

BLVR: The way you made Les plages d’Agnès can be seen as a kind of gleaning—you found material that already existed to put in your film. It is almost like you were looking into the ground, bringing up images from the past, from old films you had made, and photographs, and scenes from the films of your late husband, Jacques Demy.

AV: But gleaning is getting things that are abandoned. I did not abandon my early pictures, my photos, my early films. It’s just going through my body of work as something I can pick from—I pick this and that and that. It’s like I had a collection of my work and I could choose this one or this one. With Jane Birkin, we had a scene from a film called Jane B. by Agnès V.—a portrait I made in ’87. We had a casino scene, surrealistic, in which we had some naked people gambling. Jane Birkin was the card dealer and I was the player. I had beautiful jewelery around me, and when I lost I would take the jewelery and say, Service—being very generous, because it was very expensive jewelery. I would say, Tip.

Now, I just take this piece of film, and I make a narration in Les plages where I say I’m losing. I say that I lost my father. We are watching the roulette ball, and the ball stops and I say, That is where it fell—and he died. He lost, he fell, he died. Which is a totally different use of the same images. That was my game. And it works. You can have seen Jane B. or not.

II. “THE STORY OF A COUPLE IS ALWAYS VERY FRAGILE,ESPECIALLY OVER MORE THAN THIRTY YEARS.”

BLVR: Is each film a game, then, in some way? Is every film like you’re making a different game for yourself to play?

AV: Well, there is a song of Gainsbourg that Jane Birkin sang, and the words are beautiful in French. It says, “Le jeu et les moi.” It’s impossible to translate, because it has a very nice sound. It sounds so lovely in French. So I took that because it was the subject: I and myself and myself and I. Which is, in a way, boring, because it is a contradiction.

BLVR: You also brought in images of people from your past, like Harrison Ford. Is he a friend of yours?

AV: I never met him since he became so famous-famous. But yes, he came to the opening of Vagabond in Los Angeles. Whenever we meet he is very friendly, but, you know, these people cannot even be reached! If I knew how to reach him—I went to the country in his house where we shot in the winter, and he told for the camera the story that the studios told him, when he was young, that he had no future. Can you believe this? And that is nice to put in a film, because it is a real story in itself, so interesting.

BLVR: I read in a book where somebody said that your Los Angeles was so different from the way other people lived in L.A., because you and Jacques created a little Paris around you, with friends and food, and it was so different from the alienated Los Angeles that other people were living in.

AV: Some people meet each other again only when I’m there! Sometimes it’s like, Eh! I haven’t seen you since the last time Agnès made a little—it’s people I put together because I have been always liking them and loving them and seeing them. Jacques was invited by Columbia, and we had that incredible life. At the time I made some films. I made Lions Love and Black Panthers. I worked all the time. Then we came back ten years later with Mathieu as a child, but Jacques was not really finding a deal. I tried with the studio—but it didn’t work. I made a documentary about a woman that my son, Mathieu, acted in.

At the time, Jacques and I were arguing, and when I show this in Les plages, I use that beautiful Picasso painting called La femme qui pleure. What a painting—so strong! At that time I was down because I was so much hoping—and so was Jacques—that we could go on forever. We were disappointed more than anything. More than separated, we were disappointed. I think it’s something I can tell. The story of a couple is always very fragile, especially over more than thirty years. People know it’s not easy, and even though you have strong feeling and desire and endless love, it doesn’t always happen. Then we came back together back in Paris.

So I tried to find a language for the film—not just telling stories. I picked the Picasso painting because it said more than I could explain. I need images, I need representation which deals in other means than reality. We have to use reality but get out of it. That’s what I try to do all the time.

BLVR: Yet it feels more like life actually is—

AV: I hope it does. Because I think that’s what we need. We need to find another way or another shape or an allegory or something that tells us more. Even Vagabond—it was a fiction but it was really a documentary. I mean, it has the texture of documentary. Even if I made up every line, it has the texture of being true.

BLVR: You used to make fictional films. Why don’t you make fictions anymore?

AV: I’m not sure I’m in the mood for that. I’m trying to capture something more fragile than a regular story. I love what people bring me. I had a very good time when I did The Gleaners—even though the people are poor, and I was suffering to see the conditions, and plus they are not such lovely hearts. They are tough to each other, they beat each other, they are rude and they are violent and they drink. They’re not sweethearts, you know, but some were so interesting.

With The Gleaners, the problem was bigger than me. I wanted to catch the problem of consumption, waste, poor people eating what we throw away, which is a big subject. But I didn’t want to become a sociologue, an ethnographe, a serious thinker. I thought I should be free, even in a documentary which has a very serious subject. It made me feel very good that I could investigate a certain way of doing documentaries in which I’m present—I’m myself—knowing I’m doing a documentary and speaking with the people, telling them I have a bed, that I can eat every day, but I would like to speak to you. And they really gave me wonderful answers. We got along very well without trying to make me look like I’m what I’m not.

BLVR: How did you gain their trust?

AV: I think I got their confidence because I was not looking at them like insects that I would film. We sat down and we spoke. But Les plages is a different film, because the subject is not bigger than me. The subject is the small me, if I may say so.

BLVR: Does it feel different to make something more documentary than something more fictional? Does one make you feel more a part of the world?

AV: You are always in the world. Even in Vagabond. I am not on the road, I am not eating nothing. But in a way we all have a Mona. We all have inside ourselves a woman who walks alone on the road. In all women there is something in revolt that is not expressed. I’m interested in people who are not exactly the middle way, or who are trying something else because they cannot prevent themselves from being different, or they wish to be different, or they are different because society pushed them away.

BLVR: Your speaking of people being pushed away reminds me of a scene in Les plages where you and your brother hold hands and face the camera and walk backward. You walk so slowly, so carefully, with half smiles, almost like children. It’s so moving.

AV: Yes, because people think you are an orphan when you are a child, and don’t believe that old people can feel that they are orphans. But maybe I will take it out from the film. You know, an hour and fifty-four minutes is too much for audiences. They get nervous. I try to make it one hour forty-five.

III. “IT’S A WAY OF LIVING, CINEMA. AND I SEE MY FAMILY, I DO THIS AND THAT, I TRAVEL. IT’S A LONG PROCESS TO LET IT HAPPEN.”

BLVR: Why be an artist? Why do you make films?

AV: To share a lot of ideas—not ideas—emotions, a way of looking at people, a way of looking at life. If it can be shared, it means there is a common denominator. I think, in emotion, we have that. So even though I’m different or my experiences are different, they cross some middle knot. It’s interesting work for me to tell my life, as a possibility for other people to relate it to themselves—not so much to learn about me. There’s nothing special. I know people could tell incredible stories. People have been in concentration camps, or women being raped, or a man going to war and not recovering from it. People have been robbed and beaten. A lot of people have had strong events in their life, which I didn’t. I had a life of work and emotions. So I asked myself, Is it interesting to tell?

BLVR: And how did you decide that it was?

AV: It was an organic process. In the beginning I didn’t dare speak about me. When I did the first edit of Les plages, it was very dry and very square in a way. I was just saying the minimum. I said, Well, if this is the minimum, I don’t make it. So I tried to make it more refined. I tried to find images, allegorical images, that I could use to express things that I didn’t want to say or didn’t want to show or I was not able to find how to show. I started to look for images, including paintings, that would relate to my own feelings and experience. Which is a contradiction of the film—I want to be shown, I want to be hidden.

BLVR: You said you would shoot one day and edit one day—

AV: Not by day, by weeks. There would be weeks of editing and weeks of shooting. I did the first weeks of shooting, then I edit and I think about it, because the writing is everywhere—in the shooting and in the editing. When the editing needs it, I fix it. I say, OK, we go back, we shoot another three days. Then I do the narration. This changes the editing, then the editing needs—there’s something missing. Up and down and back. It took me six months. It’s a way of living, cinema. And I see my family, I do this and that, I travel. It’s a long process to let it happen.

It’s a way of living, sharing things with people who work with me, and they seem to enjoy it.

BLVR: One of the themes of Les plages is memory, people losing their memory, like your mother did. Is that something you fear very much for yourself?

AV: Yes. I think I’m on the way. I have to do it the way she did. She told people, Don’t worry if I say it wrong—I’m allowed to do so. My sister was suffering from it. She said, It’s terrible—she gives us the names of her brothers and sister! I said, But she’s free, let her enjoy that—and I laughed. And I teach my children, who were there, laugh! I mean, she does nothing wrong. She’s liberated from truth, in a way, from being right.

An old woman I loved very much when I was young—the wife of Jean Villard—she’s just reciting poetry all the time, which is beautiful because it means she went back to the world of poetry that she loved when she was young. That’s all she does—she almost doesn’t recognize her children, but she recites Valéry and Baudelaire. So what? We’re the ones who are suffering. She’s not.

BLVR: There’s a real generosity on the part of all the people in your film, like they are expressing love for you by being in it, rather than for any other reason.

AV: The couple I met in Los Angeles that were married on the beach, with the minister who had a yellow sock and another brown sock—I found that hilarious—and the only witnesses were the birds on the beach. I love that couple as an allegory of a dream of love that they accomplished with kids and grandkids. They are real friends of mine, so they came into the film naturally. I tried to have the film grow naturally with things that I love, and to tell things that I love, and always in a parallel way to speak about what I feel through other people’s feelings.

BLVR: You like ordinary people.

AV: I call them real people, because they have in themselves an incredible treasure—stories, a way of speaking, a way of sharing, an innocence and a perversity which I find very interesting to discover little by little.

BLVR: It is beautiful how you end the film by showing your extended family on the beach together. It reminds me of the end of One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, where you had a very similar ending. All the generations come back—

AV: Yes, but in this film, it’s the real family. It was so nice for them to agree to do it. I said, Please come and dress in white. They said, Why? What is this? My older grandson, he is twenty-two, he says, This is ridiculous! I say, Please do it for me—be in white and just move to each other—don’t dance, just move a little. And they did it. They did it in the ocean and they did it on the beach. And it was cold! The little one says, It’s so cold today! I say, Do it! Do it! It’s the tyranny of the filmmaker who wants to have the shot. And they did beautifully.

I think we need to have a nest of something which is family, and whenever it goes very well—some families don’t get on that well—but we need the idea of family—the concept more than this one and this one. It’s peaceful to think about the family as a group. I totally believe in extended families, and the good friends I have—I see them all the time. We choose our family—the family of what we believe in, people who share our opinions—it can be political, it can be artistic, it can be a position, as feminism. I quit seeing some people who were saying bad things about women; I don’t even want to meet them or see them.

IV. “I DIDN’T GO TO FILM SCHOOL. I WAS NEVER AN ASSISTANT OR TRAINEE ON A FILM. I HAD NOT SEEN ALL THOSE CAMERAS. SO I THINK IT GAVE ME A LOT OF FREEDOM.”

BLVR: Can you tell me about one of the artists who first inspired you?

AV: Well, Picasso really changed my life. It’s strange to say so, but I started to see some Picasso paintings very early. I was very young, and he was not so much known. The first exhibition was organized by the communist party, can you believe this?—because of his position during the war and all that. But the freedom he gave himself to work and change shape and change ideas and work all the time with joy—you know, the joy of painting was in Picasso, which I found beautiful.

I never met him. I took pictures at the Festival d’Avignon, but I was too shy to ask to go in his studio. It does not look like me now, but I was very shy, and shy of men also. I think there was a world that frightened me totally. How can I meet these guys when they are on another—? Plus, I’d been educated stupidly, I knew nothing about nothing, that’s part of being shy. The way younger people are educated now—but if you know nothing, it could be like an enemy in a way. I think that’s the way I felt when I was young. You understand, I was eighteen, this was back in ’46, so we also had these very frightening images of soldiers in the streets of Paris. So the effect of war, plus my shyness, plus my lack of education—I was afraid of men, really. It changes later, but it took me a certain time to adjust, yes.

BLVR: You were given the name of “Grandmother of the Nouvelle Vague.” How do you feel about that?

AV: I love that! I was thirty. I remember my photograph in the magazine and it says: “Ancestor of the New Wave.” And I looked OK at thirty, eh? So I thought, If I’m an ancestor and grandmother when I’m twenty-five, I should go peacefully to the real time when I’m an ancestor and a grandmother. No, I love that. I don’t care. I was not looking bad so it didn’t hurt my appearance, as I would say.

BLVR: You said that you were intimidated when you were young, entering the world of men, and I wonder, you mention Chris Marker and Resnais—were they more open to you than, say, Godard, or were you more curious about them, or—

AV: They impressed me. I didn’t feel they were humans I could approach or touch. They’re very bright and they were already. They were slightly older than me, but it’s very important when you’re twenty-five. People are four years older and they know much more than you, and they’re both very bright, and Renais told me a lot of things. In the editing he told me I should maybe see films: You know there is a Cinémathèque in Paris? And he said to me when the editing was done, he said, There’s Visconti. I said, Who’s Visconti? I had no knowledge at all, no knowledge of films. I’d seen few films. I knew nothing. I was interested in painting and theater at the time. Then I learned and I went to see movies.

Sometimes I say, If I had seen some masterpieces, maybe I wouldn’t have dared start. I started very—not innocent, but naïve in a way. So that’s a big freedom, you know? I didn’t go to school. I didn’t go to film school. I was never an assistant or trainee on a film. I had not seen all those cameras. So I think it gave me a lot of freedom. I see all these students, and I admire them—they’re trying to learn something, they go to school, they do film school, they go on shoots, they help. I’m sure they learn a lot, and some of them, it makes them aware of what they wish to do. I was—that’s the way I was—autodidact.

BLVR: Speaking of Chris Marker, is he standing behind the large cardboard cat in Les plages?

AV: I asked him permission to have his cat as my friend and interviewer. He hasn’t seen the film yet—the film was just finished when I ran to Venice, but he came to have lunch. He saw the cat in my garden. He knows the size of the cat. We meet, we speak, he sends little cartoons by mail almost every day. And using Guillaume-en-Egypte—I think it’s a nice way to speak about him. He didn’t want to be filmed, he doesn’t want photos, but we are friends, so I thought he should be in the film as Guillaume-the-cat in Egypt.

BLVR: Did he actually ask the questions?

AV: No, I made them up. Because it’s too simple, because he’s much smarter than that, but I just wanted him to say, Tell us about the new wave—which is not what he would ask. But I needed someone to raise the question so I could tell. I gave him the voice of my editor, so this is fake, but it’s also a testament of my friendship, and my admiration for Chris, who is a very bright man, and hardworking. He’s older than me and he still works like a real worker—he does good things. And he’s a very interesting man, really interesting, aging in a very interesting way. He’s like in the middle of a cave—have you been there? Screens and machines and he does the music and he does the editing and he has piles of books and records and things, and he thinks about other people all the time—all these cartoons about what’s happening in the world, very sarcastic cartoons, you know. He’s bright. I think he doesn’t want to meet so many people. He doesn’t eat, he has his protein sort of food, he doesn’t want to lose time in eating so he feeds himself with, you know, raspberries and protein food, and he’s OK.

I think people should be different. I love people who don’t go by the rule that you have to be careful because you’re old, you have to do this and that, you have to eat this and that. I try to do nothing. I drink rosemary when I have a lot of work to do. People take coffee, they take speed, whatever. I take rosemary. My company is called Ciné-Tamaris, which is rosemary. That’s my speed. Hot water and herb. But it’s nice to think that we have in ourselves the energy. It’s somewhere, but it’s sleeping sometimes. I try to wake it up when I need it.

BLVR: Have you needed rosemary while in Toronto yet?

AV: I could have used some. Yesterday during the screening of La pointe-courte, there was a bench in the hallway—just a bench in wood, that’s all. I lay on the bench. While I started to sleep somebody brought a pillow, but I slept an hour—they woke me up for the discussion. I said, Wake me up five minutes before! Then I went on the stage. I made myself very serious. They should have seen me half an hour before, sleeping like a baby on a bench!

BLVR: I know you think that feminism is out of fashion. Why do you think that is?

AV: Because to advance in society is slow, slow, and slow. To change history is very slow. The first two times I came to the States—black people didn’t have the right to vote—but we have seen them in France, American soldiers, black, and they come and save us. A lot of them died in France. They were doing the job of the American army. I come to the States and they don’t have the right to vote! Can you believe that? So, society is so slow. A feminist is a bore. [Spills tea] It’s OK, since my dress is tea-colored.

BLVR: And do you see feminism as out of fashion in France?

AV: People don’t speak about that now! It’s boring. I wanted to speak strongly about feminism in my life, since it’s been a struggle. People again started to be against self-control, against birth control, and against abortion. Even in France where it’s allowed, in a hospital there is a boss doctor for each floor, and if their convictions push them to say no, they can say, I don’t want abortion in my service. Even though it is legal, still they have the right to refuse. Can you believe this? And the young girls don’t even know that some people fought for them to have the pill or the—after-night pill? How do you say that?

BLVR: The morning-after pill.

AV: I put so much energy in being a photographer and then a filmmaker, and meeting Jacques and raising the kids and trying to be involved. Going to Cuba in ’62 was very exciting, and going to China in ’57, when Shanghai was not even recognized by the United Nations, was an adventure. I’ve always been like this—trying to find adventure where it’s still in its first élan—the first spring. The revolution in China was still fresh and people were going to it. And filming the Black Panthers—they turned bad two years after, but I saw them trying to make their own law, make their own thoughts, the body-and-soul theory. They wanted to be the one thinking, the one acting, not be led by white people. All of them were trying to find autonomy.

Je résiste. I’m still fighting. I don’t know how much longer, but I’m still fighting a struggle, which is to make cinema alive and not just make another film, you know?

BLVR: Would you say you are a filmmaker today for the same reasons as when you started?

AV: Sure I’m not, because when I started I did not know I wanted to be a filmmaker. You know, I started—I made a film. Then when I finished I said, Oh my god it’s so beautiful—I should be a filmmaker!