Alexander Payne makes films with an eye for incidental details. He circles his characters when they are at their most fragile and vulnerable. In Citizen Ruth, a pregnant Ruth Stoops plunges down a flight of stairs. In Election, Mr. McAllister washes his genitals in a hotel bathtub before an adulterous affair. In About Schmidt, Warren Schmidt loads up on Percodan and plunges into a hot tub with his future in-law. In Sideways, Miles Raymond accidentally encounters a waitress and her flabby boyfriend having wild sex to a televised (and muted) Donald Rumsfeld. With a sense of ease, he shares with us those perfectly perverse and uncomfortable moments that nevertheless make us laugh. In doing so, he helps his audiences reconnect and reflect on what it is to be human.

When talking to Payne, he is easily distracted. But when the subject is steered towards his love of film or his hometown of Omaha, he can talk on and on endlessly. He speaks five languages, plays piano, digs cats, and knows a bit about wine. Just don’t ask him one of the following questions about his latest film, Sideways: “Where did you get the idea?” “Why did you decide on this cast?” And that dark, inevitable question, “If you were a wine, which wine would you be?”

Payne has just returned from a monthlong tour of the Mediterranean, where he presented Sideways at film festivals in Turin, Thessaloniki, and Marrakesh. He’s now back in Los Angeles, where he is attempting to soothe his circadian rhythms, juggle award nominations, and visit with a fellow Midwesterner. This conversation took place in two parts. The first, in a telephone call to Alexander’s home in Los Angeles, and the second, several days later, when he picked up an honorary doctorate from the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

—Kate Donnelly

I. “I SAW STAR WARS WHEN IT CAME OUT, BUT I DON’T EVEN REMEMBER IT. I PROBABLY FORGOT ABOUT IT THE NEXT DAY.”

THE BELIEVER: Some critics have observed that you employ techniques of 1970s cinema. Are you consciously paying homage to that era in filmmaking?

ALEXANDER PAYNE: I don’t think I’m trying to pay homage to anything. The fact is that I was an American teenager in the 1970s and those were the movies I was watching. My idea of what an adult American film is has never changed.

BLVR: Were you influenced by films like Star Wars?

AP: It didn’t impact me at all. You know how people say, ”Oh, and then I saw Star Wars and it just changed my life”? I saw Star Wars when it came out, but I don’t even remember it. I probably forgot about it the next day.

BLVR: So you weren’t a fan of the commercially popular movies of the seventies?

AP: Well, I liked Jaws. But I didn’t think about Jaws the way I thought about One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest or Chinatown or Coming Home at the time.

BLVR: You were sitting in the Cuckoo’s Nest while your friend was next-door watching Jaws?

AP: Not at all. I remember being in high school and arguing about whether we liked Annie Hall or Manhattan better.

BLVR: Wow. It sounds like Omaha was a sophisticated movie-going town in the seventies.

AP: I remember my friend Dan Cowdin saying about Manhattan, “They’re just so neurotic and complainy. How can you like that one?”

BLVR: Martin Scorsese was on Charlie Rose the other night.

AP: How was he?

BLVR: Really great. He’s like an encyclopedia on film.

AP: What did he say?

BLVR: He talked a lot about films of the thirties and forties.Those twenty years seem to be, for him at least, the golden age of cinema. He talked about Hell’s Angels and Scarface. He also mentioned high impact films like The Searchers, Citizen Kane, and On the Waterfront. What were your high-impact movies, beginning from the time you went to the cinema as a teenager?

AP: You have to go back to before I was even a teenager. They were largely based on movies my older brothers thought were cool, like King Kong, One-Eyed Jacks, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, and Cool Hand Luke.

BLVR: King Kong? The Jessica Lange version?

AP: No, no, no.The 1933 movie. I probably saw it ten times as a kid because it would always be on TV. Those were the earliest movies I remember being cool. Later, on my own, without my brothers, I started getting into a lot of silent comedy. Chaplin and Keaton. I didn’t see much Lloyd. It was harder to get your hands on Lloyd. And then, of course, the Universal horror movies.That’s just what kids watched. Oh, and when I was nine or ten, a movie I probably saw at the movie theater three or four times with my buddies was Little Big Man. And The Sting. We were little kids, like twelve years old.

BLVR: The Sting? Very discerning taste for a twelve year-old kid.What was going on in Omaha?

AP: The Sting is a great kids’ movie. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, I probably saw it about four times the year it came out. I remember seeing Philippe de Broca’s King of Hearts probably three times. That’s a good kids’ movie, as well. And I remember it played with two animated shorts, Bambi Meets Godzilla and Thank You Masked Man.

BLVR: What is the kids’ movie demographic?

AP: I’m talking between eight and fourteen. And we loved Woody Allen’s Bananas because you got to see a girl’s breasts in it, which was very exciting for us. I would say Five Easy Pieces was a little over our heads.

BLVR: That film didn’t make the kid cut?

AP: I was nine when that came out and now it’s one of my favorite movies. But at the time, we didn’t go to see it. The big movie I saw when I was twelve, which everyone was trying to see and nobody’s parents would take them to, was The Exorcist. I finally got a friend of my parents to take me and I was actually underwhelmed by it. I think it’s scarier now than I did when I was twelve.

BLVR: So you weren’t sleeping with your lights on?

AP: The hype and buildup around it was so huge. It’s only years later that I realize how scary it is. The scariest movie for a lot of people in my generation was The Omen.

BLVR: And did that scare you when it came out?

AP: Oh yeah. That’s a frightening movie. It doesn’t completely hold up anymore, but at the time, it was terrifying.

II. “MITSUO… MI-TSUO…!”

BLVR: You reference Akira Kurosawa in nearly every interview I’ve read. Could you talk to me about the importance of Kurosawa and why you like his films?

AP: Maybe because I’ve studied them. His films made a very big impact on me. There was a time period of many, many years where anytime I could see a Kurosawa movie, I would. I devoured Donald Ritchie’s book about him, and read his autobiography. There wasn’t a whole lot of scholarship in English about him in the eighties, which was my big Kurosawa period. But it was a time when, between San Francisco and Los Angeles, you could see his films projected. Plus, I got a chance to hear him speak in Los Angeles in 1986, when he came with Ran. I don’t know, there’s just something unbelievably great about his films. They are ferocious. He tells a good story, and he’s not afraid of anything. They are deeply, deeply passionate in an unsentimental way. Only the films he made at the end of his life were more openly sentimental.

BLVR: Do you consider Ikiru a sentimental film?

AP: I think whatever sentimentality it has is very honest and earned. I saw it for the first time projected at Stanford, and about a half an hour into the film, there’s a montage about Watanabe’s son Mitsuo. He’s accompanying his son to have an appendectomy, cheering him on when he’s a loser baseball player, sitting in the back of a car following behind the wife’s hearse when the man is widowed. The motion from shot to shot often matches. And then his son calls down from upstairs, “Dad,” and the father says, “Mitsuo… Mi-tsuo…” [Alexander employs a specific and convincing Japanese accent.]

BLVR: [Laughs] Perfect inflection.

AP: And then he leaves the frame and you hear him run up the stairs and the son says, “Be sure to turn off the lights. Be sure to lock the door when you go to bed.” Pause. Pause. Cut. Look down and there’s the actor Takashi Shimura with his head resting on a step. He only made it two-thirds of the way up the stairs before his disappointment. I hadn’t seen a movie that had me crying so early. When I was in film school, I watched Kurosawa movies. This is before I had videos of them, and I would take notes on every shot. I would write down nearly every shot and start to memorize the films.

BLVR: You seem really well-organized and meticulous in that regard.

AP: Not always.There have been times in my life when I have been, but it’s harder for me now. My life is a little bigger and all. When I was in film school, I would go watch movies and write down shots. I used to see a movie,come home, write my reaction to it, and talk about cool shots and cool sequences. I still do that sometimes.

BLVR: What’s the last film you remember doing that for?

AP: The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing. I did it about three weeks ago in Turin, Italy. I couldn’t believe how good that film was. Apparently it’s fairly obscure.

BLVR: Sideways was based on a novel by Rex Pickett. What’s the greatest challenge in adapting a book for film?

AP: It’s no different from writing an original. In fact, the way [writing partner] Jim [Taylor] and I work, not always, but in general, is that we read the book a few times and then stop referring to it. We then write an original based on our memory of the book. That’s sort of how we work. So it’s as though we are always doing originals.

BLVR: How do you come across books these days?

AP: I have precious little time to read. I sometimes have to dedicate that time to reading books or scripts sent to me, otherwise I’ll never get around to reading them. But then I often grow resentful of having to do that because I think about all the books I’m not reading. I’ve never read Proust. I’ve never read James Joyce other than A Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man. I’m woefully underread in Faulkner. I can’t even talk about keeping up with new stuff.

BLVR: What about F. Scott Fitzgerald and Hemingway?

AP: I was never a very big fan of Hemingway. And Fitzgerald, yes, but mostly in high school. In college, most of the literature I read was in Spanish. I am very well-read in Garcia Marquez, for example, and Vargas Llosa. You know, the classics along with some of the great Mexican and Argentine writers and some Spanish writers.

BLVR: That makes sense. Your first thesis film was an adaptation of a novel by Ernesto Sabato, El Tunel [Midwestern accent applied].

AP: El Túnel [thick Spanish tongue employed].

BLVR: [Laughs] Thank you. You sound like the fellow on Jeopardy.

AP: Did he ever lose?

BLVR: He finally lost.

AP: Who beat him?

BLVR: A woman. I missed his televised demise. Clearly, he’s not missing any meals. He won over two million dollars.

AP: Yeah, that’s unbelievable.

BLVR: Would you ever have auditioned for Jeopardy?

AP: Yeah. Except I don’t know sports.

BLVR: Do you enjoy sports?

AP: I like playing them, not watching. I used to play a lot of tennis and I don’t anymore, but I’d like to get back to it. I used to play a lot of racquetball. Right now, I do yoga and go to the gym and throw weights around and jump on the machines. I swim when I can. I like to swim in the ocean. That’s pretty much my favorite thing.And being in a stream and hopping from rock to rock. I like that a lot.

BLVR: Getting back to writing, will you ever write a novel?

AP: I don’t know yet. I would like to try short stories and poetry, but I’m afraid of poetry. I think filmmaking is hard but poetry is really hard. Good poetry. Poetry is kind of the most important thing, in a way. I get a poem sent to me every day by Garrison Keillor.

BLVR: How?

AP: I get the Writer’s Almanac. Do you get that?

BLVR: I don’t. How does one subscribe?

AP: You subscribe to it online at Minnesota Public Radio and then every day Garrison Keillor sends you a poem; sometimes new, sometimes classic, never too long. And biographies of writers or notes about important events that took place on that day.

III.”EVEN THOUGH I CAN NEITHER CONFIRM NOR DENY THAT I DO OR DO NOT INTEND TO RUN FOR OFFICE ONE DAY, I MAY OR MAY NOT HAVE A PLAN FOR THAT WHICH I’M NOT PREPARED TO DISCUSS.”

BLVR: You just went to Washington, D.C., to pick up the annual Distinguished Nebraskan Award. What were the prerequisites for such an award?

AP: I think you have to be from Nebraska. They have given it to a wide variety of individuals, from politicians to educators to corporate leaders.

BLVR: Would you ever consider running for public office?

AP: I’m not prepared to confirm or deny the possibility. But I have thought about it, yes. [Pause] What’s making you ask? Did someone tell you that?

BLVR: No. You just seem politically inclined to me. Hypothetically, how would you go about campaigning?

AP: Well, even though I can neither confirm nor deny that I do or do not intend to run for office one day, I may or may not have a plan for that which I’m not prepared to discuss.

BLVR: Do you think it’s right for a film director to pursue other interests? Wouldn’t a political life interrupt a film career?

AP: It would obviously interrupt a film career. But one of the reasons I wanted to be a filmmaker in the first place was that it allows me to be a generalist in life—to immerse myself in different topics, different disciplines, different cultures, different issues, different academic fields.

BLVR: Growing up, which major political figures in Nebraska influenced you? Did you have any “good guys” to look up to?

AP: The neat thing about Nebraska is that even though it’s a solidly Republican state, the voters tend to look at the character of the person running. For example, Nebraska has had two democratic senators at one time. In recent history, it’s the first state, and I think the only state, to have two women running against each other for governor. And, while it’s a very conservative Republican state,it produced George Norris, a progressive—who was actually a Republican, but a progressive in the old way Robert La Follette of Wisconsin was. It produced Herbert Brownell, who was Eisenhower’s attorney general and helped pioneer, and then enforce, some civil-rights legislation. There’s a very comforting history of freethinking in Nebraska that I appreciate. In fact, when I went to Washington a few weeks ago,I made a point of visiting Republican senator Chuck Hagel so I could shake his hand and tell him how encouraged I was that there was a Republican senator who was publicly and actively disagreeing with the president about how the war is being pursued. Which is not to say that I necessarily agree with his points of view on many other issues. But I respect the man, who’s unlike so many politicians nowadays, who seem to have given up the idea of thinking for themselves.

BLVR: Politically speaking, what kind of household did you grow up in?

AP: My father is Republican and my mother is Democrat.

BLVR: That’s the Midwest. Do you think the Midwest has become conservative now?

AP: It has always been so. It’s so easy to talk about “red states” and “blue states,” but it is not as though everyone is of a certain political bent. We know there is diversity everywhere, maybe less diversity in some places. You certainly don’t find a lot of ethnic diversity in North Dakota, for instance. In spite of the trend, I think it’s really hard to generalize about people. When you get to know them, you discover everyone’s got a story. It’s hard to generalize. There just happens to be much deeper strains of conservative attitudes ingrained in the Midwest. And obviously, in the South, there is something else again, and that’s just disappointing. The problem for me is that people respond to labels like conservative, Republican, Democrat, Liberal. Bush and company do not seem to me to be real Republicans. They are virulent ideologues who have commandeered the word “Republican.” Many people fall for it perhaps more than they would or should if they just thought a little bit more or read a little bit more.

IV. “SCORSESE IS LIKE AN ENCYCLOPEDIA. I’M JUST A POCKET GUIDE.”

BLVR: Would you have any interest in directing a political film?

AP: How would you define a political film?

BLVR: A political film is what’s timely right now. Not necessarily the war in Iraq, but the fear and paranoia going on inside America.

AP: Yeah, I’m surprised we haven’t had science fiction like we had in the fifties, because we have generalized fear. At least we’re told we have fear. Are people really afraid?

BLVR: I think they might be. What would a political film mean for you?

AP: The genre does not matter. It’s the concerns. A political film can be a science fiction; it could be a Western. Little Big Man is a political film.

BLVR: What about a black and white silent film?

AP: I would love that, but it might be in color. I’m going to work in black and white cinemascope the film after next. And silent film is beautiful. At its apex, right before the talkies came in, telling a story through images had reached a sublime and sophisticated place. And many people, as you know, thought the talkies would be the end of cinema because they would just film people talking. It would be filmed theatre in a way. It would decrease cinematic beauty and it certainly did for a while. Have you seen Sunrise?

BLVR: I have not.

AP: You have to make it the first film you see when you hang up with me. You must see Sunrise.

BLVR: You had the benefit of a film-school education. You’re like an encyclopedia.

AP: Scorsese is like an encyclopedia. I’m just a pocket guide. A stocking stuffer.

BLVR: Steven Soderbergh and Martin Scorsese have recently chosen to make big-budget films. Do you feel an obligation to dabble in the mainstream?

AP: I don’t know how to answer that question. It’s not just a matter of how much money you spend on a film. I mean, are my films mainstream? They have always been financed by studios. This will be the third film in a row that makes a profit. This will be my third film in a row nominated for an Oscar. Am I a mainstream director? I don’t know. I don’t use any label. I’m just a filmmaker. I’ll take the money wherever it comes from, as long as I have creative control. I make movies for studios that turn a profit and are nominated for Oscars, which sounds fairly mainstream to me. Yet I’m referred to as an indie director. Maybe that just means I make personal films, or that the degree of creative control, which I’m lucky enough to enjoy, is evident.

BLVR: Critics like to gripe about veteran directors who don’t evolve or adapt to audience expectations. Should a filmmaker worry about his relevance?

AP: Can you control how relevant you are? I don’t know how you control that. Sometimes the more you try to do something, the more it eludes you. I think you either are or you are not. And no matter what the budget—I don’t know how budget impacts relevance. Is Sofia Coppola, who made her film for four million dollars, more or less relevant than Chris Columbus, who made the first two Harry Potter films? How do you define relevant? To my eyes, these are relative and vague terms.

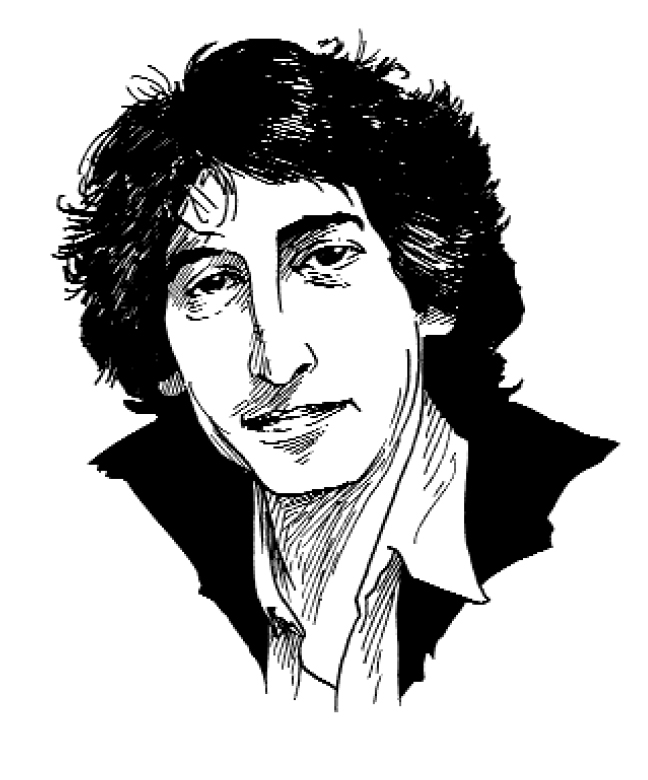

BLVR: Did you have creative control over the film poster for Sideways?

AP: Well, I told them it should be a graphic and not photographic.

BLVR: It reminds me of an old foreign-film poster.

AP: Yeah, good. That was definitely the idea.

BLVR: The Santa Barbara Film Commission recently ordered a second printing of “Sideways, the Map.” There’s also a “snob-free” wine-tasting tour for $79. Have you sparked some sort of pop-cultural phenomenon in the way of a new, non-Napa Valley?

AP: It seems that way. I didn’t try to do that. There are people watching the film and there’s a general interest in wine anyway, at least more so than there’s been in the past. Every once in a while, someone will email me something about a wine critic talking about it or how a wine store has seen its sales of certain wines go up. It’s interesting.

BLVR: In Rex Pickett’s book, he showcases a 1982 Latour, but you chose a 1961 Château Cheval Blanc, which happens to be the year you were born. Did you pick that particular wine because it corresponds to your birth year?

AP: 1961 was a good year for Bordeaux. I just wanted it to be an older wine, a more special one. I think I did note the fact that I was born that year.

BLVR: I ask because I had a 1976 bottle of Château Haut Brion that my parents bought me when I was born.

AP: Oh wow. Fuckin’ A.

BLVR: Yeah. It was to be opened when I got engaged, which I told my dad would be in the distant future. So we opened it, and it was great. Is life about drinking what you have when you have it?

AP: If you’re smart.