Aline Kominsky-Crumb was born in 1948 in New York. She briefly attended SUNY New Paltz before running away to Manhattan’s Lower East Side, subsequently spending one semester at Cooper Union before moving to Tucson, where she earned a BFA in painting from the University of Arizona. At age twenty-two, freshly divorced, she picked up and moved to San Francisco to join the burgeoning underground comics scene, inspired by cartoonists like Robert Crumb (whom she later married) and pioneer Justin Green, whose 1971 Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary inaugurated comics autobiography.

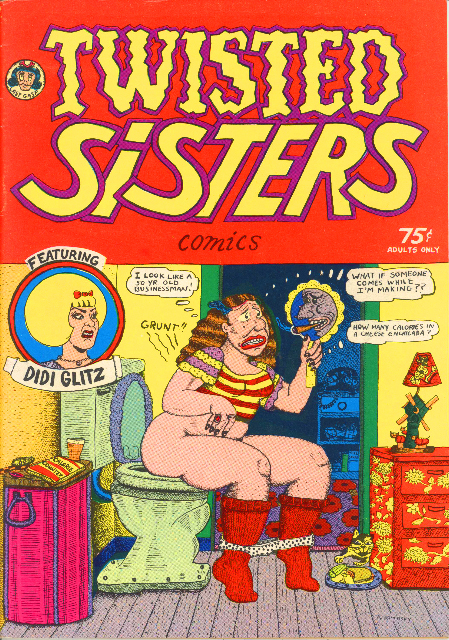

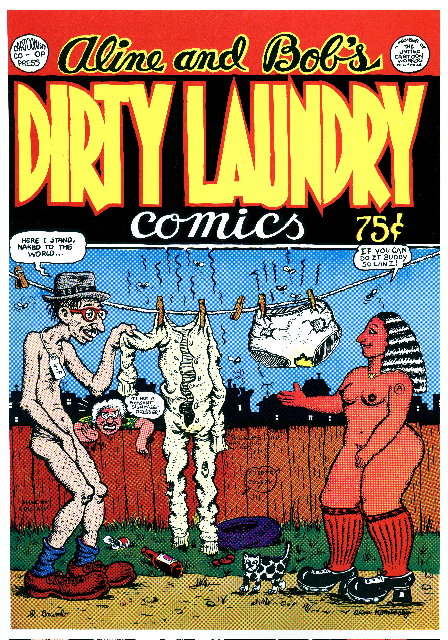

Kominsky-Crumb created what is widely regarded as the first women’s autobiographical comics story with her piece “Goldie: A Neurotic Woman,” which appeared in 1972 in the premier issue of the underground publication Wimmen’s Comix, earning her the title, as she puts it, of “the grandmother of whiny tell-all comics.” She continued to publish her work in underground titles such as Wimmen’s Comix, Manhunt, Lemme Outa Here!, Dope Comix, and Arcade, among others. She edited the acclaimed Weirdo for seven years and founded the comic books Twisted Sisters, Power Pak, Dirty Laundry, and Self-Loathing Comics (the latter two with Robert Crumb).

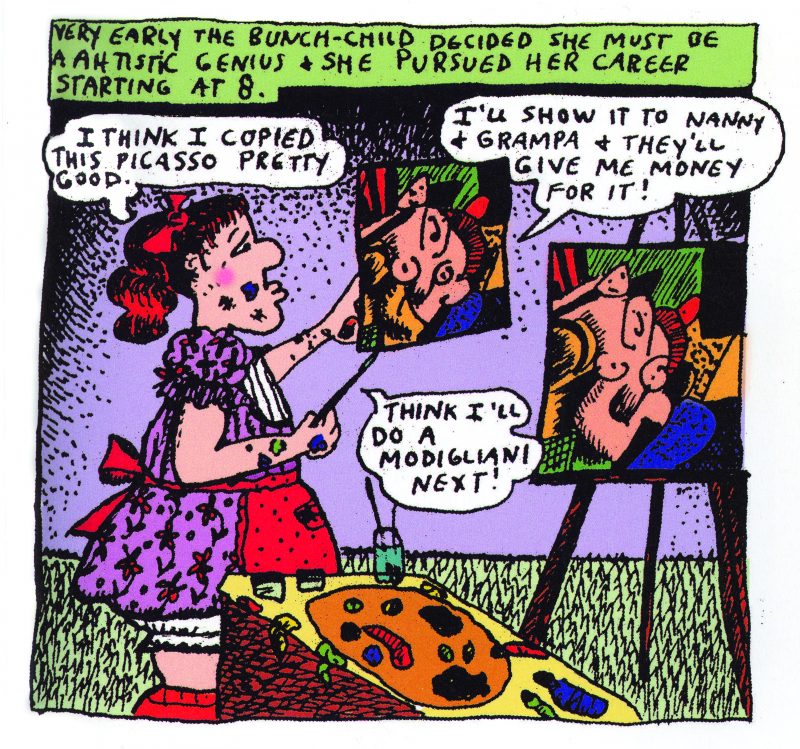

She has published three books: 1990’s Love That Bunch (named after her alter ego, “The Bunch”), 1993’s The Complete Dirty Laundry Comics (with Robert Crumb), and 2007’s Need More Love: A Graphic Memoir, a 384-page life narrative that showcases Kominsky-Crumb’s range as a visual artist in many different realms in addition to comics. Her next book will be a collaborative comics work with her husband, published by W. W. Norton. The couple’s collaborative comic strips have been appearing in the New Yorker since 1995.

I interviewed Kominsky-Crumb on the telephone on July 27, 2009. I was in my office in Cambridge; she was in her tall—nine-level!—stone house in Sauve, France (and within range of her husband, who piped in a few times). About a month later, she received me at her home, where she and Robert each have studios (she actually has two). Kominsky-Crumb not only walked me through her large and diverse body of work, much of which lines the walls of her home, but also consistently prepared me home-cooked meals—including chocolate cake—and took me to her very vigorous exercise class. The last night Aline and Robert and I were joined by her daughter, the cartoonist Sophie Crumb (Belly Button Comix), who lives about twenty minutes away and is expecting a baby boy—a subject at the center of Aline and Robert’s new, long collaborative story. “It’s about living in France for the last twenty years,” she says, “and we’re now totally immersed because our daughter is producing a French child.” Kominsky-Crumb, along with Sophie, regularly shows her work in an art gallery in Sauve that she runs with several other artists.

—Hillary Chute

I. “ART SCHOOL KIND OF RUINED [PAINTING] FOR ME”

THE BELIEVER: What was it like growing up in Woodmere, Long Island? ALINE KOMINSKY-CRUMB: Horrible. When I was growing up, my elementary-school was 95 percent Jewish. [Kominsky-Crumb is Jewish.] And it was all these really upward-striving, crass, nouveau-riche Jews, just incredibly competitive and totally materialistic. Into clothes, they all had nose jobs, and if you didn’t have every single thing, the latest thing, that second, you were a total loser. It was just really, really harsh. There was nothing else of interest going on. It was just the most boring place you could imagine, and fascist in its social conditions and constraints. But when I was fourteen I started sneaking into Manhattan, going to the Village, going to museums and looking at art and everything. I started painting when I was eight years old. That was something that kept me going.

BLVR: You took art lessons when you were little and then your parents stopped paying for them.

AKC: They thought it was stupid. Which made me think it was good.

BLVR: And your grandfather had been a painter?

AKC: My father’s father was a painter, but I never met him. One day after my father died and I was cleaning out the house, I found these two paintings in the garbage. They were painted by my grandfather, so I took them. I still have them now. My mother was throwing them away. [Laughs.] “Eh! Get rid of that junk!” They were from the 1920s. He wasn’t a serious painter, but they were kind of interesting.

I had no exposure to any culture. My parents and my whole family were just into making money. That’s all they cared about. The thought of being an artist was completely stupid to them, though they said I could be an art teacher.

BLVR: Did you always feel like you wanted to be an artist?

AKC: I drew a lot to relax. Maintaining my sanity in some way. It just became an important aspect of my coping mechanism very early on. So I didn’t think about it that much.

BLVR: When you were in art school, it was during the abstract expressionist moment, wasn’t it?

AKC: From eight years old all through high school, I had my own style and my own vision, very strong, and I was really quite developed. Then I went to art school. It completely confused me. I didn’t know what to do, and everything I did was bad, and they didn’t like my work. I completely stopped developing in my own way, and I just got lost. So I started doodling on the side in notebooks, making humorous drawings and writing things down. That was sort of how I eventually went into drawing comics. I gave up painting then because I couldn’t see what to do with that. Art school kind of ruined that for me.

But it also made me appreciate comics. Right around that time, when I was in art school, I saw the first Zap comic and I couldn’t believe it. I just couldn’t believe it. And shortly after that I saw [Justin Green’s] Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, and that was just the ultimate thing for me. When I saw Justin’s work, I knew how I could tell my story. When I saw Zap Comix I was completely impressed by them, but those guys were so good that I couldn’t imagine myself doing what they were doing. It was too good; it was too hard. But when I saw Justin’s work, it gave me a way to see how I could do it. It helped me find my own voice, because it rang so true for me. The drawing was so homely and it was so personal, and I thought it was the greatest thing I’d ever seen in my life. I realized I just wanted to do something like that. I didn’t care, I didn’t think about who would read it or why they would, but I just wanted to do something like he did, for myself.

BLVR: I read that he was studying painting too, abstract expressionist painting at the Rhode Island School of Design. It’s interesting that you both had that abstract expressionist background, and then went to comics.

AKC: Well, probably because we couldn’t relate at all to the abstract expressionists. It just didn’t do it for us, at all. Both of us were tortured and had a need to express ourselves, and were searching for some way to do it.

Robert [Crumb]’s work was really interesting because he had an aspect of the old comics from the ’20s that we all loved, that was really familiar, and [felt like] home, and very reassuring, but then it was also charged with this total psychedelic vision. So it just touched something so deep.

We felt, “Oh my god,” you know, “this is it.” And it definitely set off a whole other set of possibilities, I think, for a lot of people. It was definitely a super-charged moment there. Robert’s work and everything that came after it changed graphic art forever. It changed fine arts, too. But it really changed the way everything looked, you know, instantly. He influenced an entire generation in France, too, and everything that came after as well. We didn’t even know that was going on. They were pirating his work over here all through the ’70s and we didn’t even know it.

We felt, “Oh my god,” you know, “this is it.” And it definitely set off a whole other set of possibilities, I think, for a lot of people. It was definitely a super-charged moment there. Robert’s work and everything that came after it changed graphic art forever. It changed fine arts, too. But it really changed the way everything looked, you know, instantly. He influenced an entire generation in France, too, and everything that came after as well. We didn’t even know that was going on. They were pirating his work over here all through the ’70s and we didn’t even know it.

II. “THERE WAS A BAND CALLED TWISTED SISTER; THEY STOLE YOUR NAME.”

BLVR: Will you tell me about how “Goldie,” your first comics story, came about?

AKC: Well, my maiden name is Goldsmith. They used to call my father “Goldie,” so it went back to my father. And also since I didn’t like my father very much, I sort of hated that name, and my character was a part of me that I felt was repulsive, and the name sort of fit that character.

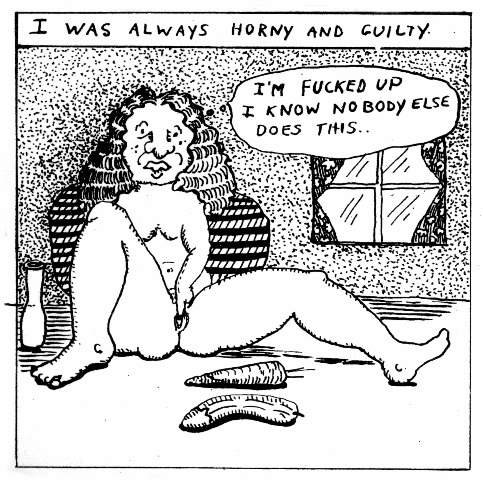

BLVR: I was so struck that in one panel, there’s that scene where your dad’s coming towards you, saying, “C’mere,” and you’re imagining him with this erection and it’s really gross. And then in the next panel, there’s an image of the Goldie character masturbating. And that’s what is so appealing to me: even though you’re grossed out by your father’s sexuality, you’re not victimized by it. It doesn’t keep you from being sexual yourself.

AKC: It’s true. I was grossed out by my father, particularly, and he made me feel ugly, but I still really wanted to have my own sexual thing. I wanted to have fun, and I wanted to experience everything. So I wasn’t turned off.…

Putting that ugliness out there liberated me from it in a way, too. Because part of me didn’t feel that. It was something put on me. So it was sort of an exorcism to get rid of that. Underneath I always felt very optimistic, like that wasn’t really me. There was something a lot better going on. I always felt strong, and I always felt that I would get away from my family, away from that horrible place and those horrible values, and I would have wild adventures and find out what was really going on. And I did.

BLVR: What happened with Wimmen’s Comix?

AKC: It started off because at that point, anything was being published, and since there was never an [ongoing] woman’s comic before, everyone thought, Oh, that’s a good idea. So Trina [Robbins] got that together. There weren’t even enough artists…. I moved to San Francisco just at that time, and someone introduced me to Trina so I got in the book; anybody that was willing to do anything got in the first book. I met Diane Noomin [creator of Didi Glitz] on the bus—I saw her drawing in a sketchbook. I said, “Oh, you wanna draw a comic?” She said, “Yeah, why not?” So I said, “Come on, I’m going to a meeting.” And she just got off the bus and came with me. And then she got into it.

BLVR: That’s a very adorable story.

AKC: You know, we were just looking for anybody. But after a while, it became this “women’s art collective,” in quotes, and Trina was the head of it. Basically that group was divided into feminists who were anti-men, and powerful women who wanted to do what they wanted to do, but also liked men and wanted to have sex, too.

BLVR: So it was about sexuality.

AKC: It was about what you considered having power over your life.

BLVR: Did Trina have any substantial things to say about your aesthetic? I mean, was it sort of like an ideological difference and an aesthetic difference?

AKC: Trina was very down on autobiographical comics. She discouraged me from doing it when we first started doing those comics together.

BLVR: What did she say?

BLVR: What did she say?

AKC: She just said, you know, “Who wants to read about your personal daily things? That’s not interesting. People want, you know, to be uplifted in their work, and…” [Robert Crumb speaks in the background.] Robert’s trying to say something. What, Robert? Yeah, that’s right. Trina said, “Who wants to read about whether you’re worrying about being fat and ugly?”

BLVR: I do, actually…

AKC: Well, so do I. It turns out, actually, people do want to read about that. If you think about what kind of comedy people like—like Larry David, and all this reality stuff that’s come since then—that is what people want to read about. But at that time, people had different attitudes. Graphic novels hadn’t become an art form yet. Underground comics were a transition period from old-fashioned traditional comics to what you have now.

And Trina couldn’t understand why I would draw myself on a toilet. I would completely deconstruct the myth or romanticism around being a woman—all that stuff. I was just vulgar and gross and everything. I enjoyed pushing that in people’s faces. For me that was somehow satisfying.

BLVR: How did you decide to make Twisted Sisters?

AKC: Part of it was because Diane and I were disgusted with the Wimmen’s Comix thing. We both were really alienated and felt left out of a lot of the comics, and they were really treating us horribly. We felt a shared vision that was much more compatible than we did with any of the other women in the group at that time. So we decided to do our own book, where we wouldn’t have to put up with all that political correctness and all that crap. We each wrote about a hundred names and we came up with that name together. There was a band called Twisted Sister; they stole our name.

BLVR: I loved them when I was a little kid.

AKC: Well, anyway, they got it from our comic.

BLVR: Was there a response to the cover?

AKC: It came and went unnoticed, to tell you the truth. But years later, I remember [cartoonist] Peter Bagge said to me, “You know, I just looked at Twisted Sisters and I realized: you drew yourself on a toilet! I mean, how could you do that?”

I said, “I guess the reason I did it was because, when I started drawing comics, I thought, Oh, this is neat, because it’s really nice to read comics on the toilet, and I’m glad I’m making art to read on the toilet, so I guess that’s why I put myself reading comics on the toilet.” [Laughs.] I didn’t think of it as being unique for a woman to draw herself on the toilet; it just seemed natural to me. But the comic—really, there was no impact. We had no feedback; it sold hardly any copies. Nobody cared, nobody liked it, and that was that.

Every single thing I did was like that. I had no success ever. In any terms. I never had, you know, universities asking me for my opinion, or to give talks. I never had any kind of feedback from the fine arts scene or the comics world. Nothing. [Laughs.]

BLVR: Well, that gives your work a certain purity, right? It’s really being creative without external forces bearing down on it…

AKC: Maybe if I had, for some weird reason, made it into the mainstream culture, somehow that might have ruined it. Robert got screwed up by being famous really early. It was really hard for him after that.

BLVR: But then after Twisted Sisters you did your own solo comic, Power Pak, so you really were undaunted.

AKC: [My work] never sold, so even my publishers… they’d always be really disgusted. And Gary Groth was good enough to publish [my book collection] Love That Bunch, but that’s just because the Hernandez Brothers and Peter Bagge made him publish it because they really like my work.

BLVR: What was the issue with finding a printer for that book?

AKC: Men thought some of the things I drew in there were so disgusting, that they couldn’t… they were Christian printers, and no one would print it.

BLVR: Fantagraphics was using a Christian printer?

AKC: They were at that time, yeah, because they just wanted the cheapest printer. You know, a lot of printers were Christian. What could you do? They went to the cheapest printer they could go to, I guess, and these guys refused to print it. They went to a couple of printers, actually. And to their credit, they kept persisting until they found someone that would do it. Because, you know, men doing porno is fine. But the way I drew degrading, ugly sex and everything—it was really a turnoff to men. They hate it.

BLVR: This is a question that’s always actually deeply puzzled me about comics. Because it’s not like there isn’t other “pornographic” stuff that gets published all the time. So why did you run into trouble, and why did [cartoonist] Phoebe Gloeckner run into trouble with printers?

BLVR: This is a question that’s always actually deeply puzzled me about comics. Because it’s not like there isn’t other “pornographic” stuff that gets published all the time. So why did you run into trouble, and why did [cartoonist] Phoebe Gloeckner run into trouble with printers?

AKC: I think because we’re women drawing that. And really strong, powerful, subversive ways of looking at sex and male-female relationships—I think it’s very disturbing. Because it’s not status quo.

BLVR: I’m interested in your role as an editor and as a tastemaker in general. You were the editor of Weirdo from, what, ’86 to ’93? And you founded Twisted Sisters and Power Pak and Self Loathing and Dirty Laundry. I mean, that’s a major role in comics.

AKC: I lived way out in the country, and that whole time I did all that work by myself with Robert, way out in the middle of nowhere. It’s very personal work, and if it was in any way influential, it’s, you know, probably because I’m this typical baby boomer, raised in the suburbs of New York, who was a hippie and went through this personal journey that maybe a lot of other people could relate to.

And, maybe because I took a few steps back from it, I was able to comment on it. When I was editing Weirdo, there were no other vehicles for new work that existed at the time. I got so much work, so many submissions. You couldn’t help but make a good magazine. I had to turn down really good things. It was horrible. And a lot of people got their start in that magazine. You know, like Julie Doucet, I put Carol Tyler in there, Dori Seda….

BLVR: And Phoebe Gloeckner, right?

AKC: Phoebe, yeah. I met Phoebe when she was fourteen, because she found my work under her mother’s mattress. It was just a very rich time. There were all these people starting out at that time who had been influenced by the first generation of cartoonists in the ’60s, and all these younger people coming out with work.

III. “WHAT ELSE COULD YOU DO BUT EMBRACE YOUR YOKO-NESS?”

BLVR: You started collaborating with Robert in your comic book Dirty Laundry in the early ’70s.

AKC: When the first Dirty Laundry came out, I got hate mail that you wouldn’t believe. I have two lines memorized which I can recite to you. One was: “Maybe she’s a great lay, but keep her off the fucking page.” And the other one was, “Keep her in the kitchen. You do the cartooning.” It actually spurned me on to be even more outrageous and impose myself even more, you know. That’s when I started calling myself “Yoko Buncho.” [Laughs.] What else could you do but embrace your Yoko-ness?

BLVR: What do you think the issue was? Was it that these were the fans who really responded to the craft part of Robert’s work, and they saw your work as not as crafted?

AKC: Yeah, of course. He was such a genius, and they were such devoted fans. The fact that I would dare to put my flat scratching on the same page with a master like that, they thought that it was incredibly nervy. They just couldn’t believe that I would dare to do that. Even some of Robert’s friends really thought I was, like, very pushy and…

BLVR: Just like Yoko?

AKC: Yeah. Just like Yoko. Exactly. I am not exaggerating.

BLVR: What’s the difference between the Dirty Laundry stuff and then the less sexually-explicit New Yorker stuff?

AKC: Well, the New Yorker thing we got down to this almost George Burns and Gracie Allen routine. We go into character when we work.

BLVR: Right.

AKC: He feeds me the straight lines, and I take all the pratfalls, you know? Dirty Laundry kind of gradually developed that. The first Dirty Laundry we did just to amuse ourselves, and then someone published it. And then we got into it more, and started thinking of it more as making coherent and entertaining stories.

AKC: He feeds me the straight lines, and I take all the pratfalls, you know? Dirty Laundry kind of gradually developed that. The first Dirty Laundry we did just to amuse ourselves, and then someone published it. And then we got into it more, and started thinking of it more as making coherent and entertaining stories.

We started doing the New Yorker stories as journalists, going to Fashion Week and Cannes and stuff like that, and it was really fun. Then we started doing things like that story about the tape dispenser. We’re doing a story now about our vacuum cleaner. What we had to go through to get a vacuum cleaner in France. That’s something that’s revealing about life here. It’s kind of a good story. When we do those comics we get into another role. It’s like being a stand-up comic. I’m not digging deep into my painful childhood that much. It’s way more pleasurable to work on.

BLVR: I think the sexual stuff in Dirty Laundry is amazing, too.

AKC: Hm.

BLVR: It’s very explicit, but it’s this consensual thing. There’s something sort of amazing about all of the representation of sexuality in a couple.

AKC: I can’t judge that at all. I have no idea.

BLVR: I’ve never seen anything like it before.

AKC: What other husband and wife have ever done a comic before? Nobody. There’s no other couple that has ever done it, so of course you’ve never seen anything else like it. And then our daughter’s in it, too. I mean, what other family has done comics before? Nobody. There’s nothing to look at that came before, and there’s nothing after it as far as I know, either….

BLVR: Has your mother still not seen your work?

AKC: Well, after the film that Terry Zwigoff made [Crumb], she was deeply hurt and everything.

BLVR: Why did she see it?

AKC: I told her not to see it. But all of her friends saw it and she was so humiliated she had to go see it. She didn’t talk to me for three months. But after that she didn’t want to really cut off from me. I said, “Look, you know, I did a lot of work that’s really harsh and everything when I was in my twenties. That’s how I dealt with a lot of things. That enabled me to get over it. But I would never do any work like that now, so can we just put it behind us?” And she said, “Yes, let’s do that.”

She looks at my work in the New Yorker. The work I do now is not offensive to her. Since we work for the New Yorker and Robert does things that are acceptable, you know, she’s forgotten about it. But she was very hurt at the time of the movie. She didn’t see any of my work up until then. I was able to hide it from her. Because why would she see underground comics, you know? She thought I painted and I was teaching painting classes, and I taught exercise class, and I did some comics, but she didn’t want to know about it. It was just some underground hippie nonsense, so she didn’t really worry about it. Until it was, like, shoved in her face.

I felt guilty about it, because, you know, when Terry made that film, I thought no one would ever see it. First of all, I thought he’d never get enough money to even finish it. And then if he did finish it, I thought it would be in a few small art theaters. Even in the film, he says, “Well aren’t you scared your mother will see this?” I said, “No, my mother would only see a film if it came to the mall or the gym.” And it did. It did. All her friends saw it and said, “Oh my god, how could your daughter do that to you?” She had to go see what they were talking about.

BLVR: I forget, does the film show that big image of her with the sharp teeth that you drew?

AKC: Yeah, exactly. I’m holding it up and saying, “Yeah, this is my mother. A-ha-ha-ha-ha.” And Terry says, “Aren’t you scared she’ll see that?” I said, “Nah,” as if I didn’t care. You know, it’s really mean.

IV. “I FEEL LIKE I’M DRAWING IN BLOOD.”

BLVR: Tell me about your most recent book, the memoir Need More Love.

AKC: The publisher went out of business the night that my book came out. I was in the middle of a talk at the New York Public Library when they went out of business. But that’s a long, long story.

That book, for me, exists in the twilight zone. But as a result, I’ve gotten more feedback on that book than I’ve ever gotten from anything else I’ve ever done. It seems to go around in these weird ways. I’ve gotten so much feedback on that book, which I never made a cent on, and has never been officially distributed or anything. [Laughs.] Some other publishers have wanted to republish it and I don’t want to. I just want to leave it exactly as it is, because now it’s like a guerrilla art statement.

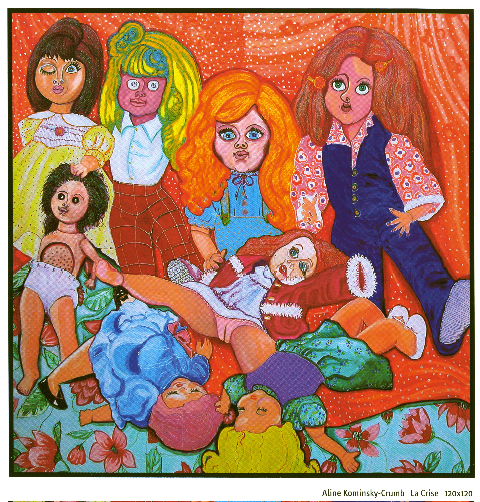

BLVR: I love the multimedia autobiography aspect of it, where there are comics, and there are prose sections, and then there are your paintings…

AKC: That was completely experimental for me. I had an idea of doing this, like you say, collage, multimedia, enhanced comic: to have more text, and then to explain some of the comics I had already done, and then also to add the painting, and all my other artwork, which is a very important part of my life that has never been seen, with the comics. I wanted to put it all together to sort of complete the picture.

BLVR: Can you describe your multimedia artwork? I love your shrines and sculptures.

AKC: That was influenced by a long trip to India, where I thought people made beauty out of nothing. So I decided to make beauty out of garbage. I started looking through the dumps in India and I made collages out of garbage; I made eight collages while I was there. And the local people, out in this rural village, were looking at me like, “This nutty American, why is she going through our garbage?” And I said, “Well, I’m gonna make artwork out of it.” I decided I would have a little art show. I was with another artist friend, and she was making stuff too, so we had a little show in front of our hut after two weeks. That was the best art opening I ever had. The people came, and they were lighting incense, and saying, “God gave you this gift, this art gift, look what you did, you made a miracle out of garbage.”

BLVR: That’s so flattering.

AKC: It was the most appreciated I ever felt as an artist, ever. Nothing ever came close. That inspired me to keep wanting to make more shrines out of junk, so I started going to the flea market. People would be selling bags of, like, Barbie parts and stuff like that. I started using a lot of things that were just the plastic garbage of our society, especially the stuff kids get. Trying to turn that into sacred objects.

BLVR: How would you describe your style in comics?

AKC: [Laughs.] Lack of, my lack of style.

BLVR: I don’t think you have a lack of style.

AKC: I’m just scratching in the most, I don’t know, emotional, raw way. I’ve done hundreds of life drawing classes and all kinds of stuff, but none of it seems to affect the way I draw when I’m drawing comics and writing about myself. I’m so emotionally charged when I’m doing that, I can’t really control what comes out. It just comes out in a very direct form. In a way, I’m lucky that I can access that. In another way it’s horrible because I can’t refine it or improve it and make it look more, like, acceptable. My paintings are more visually appealing in a certain way. People are sometimes surprised when they see my paintings. I mean, they’re crazy-looking, but they’re not as tortured.

BLVR: Your comics aren’t torture to draw, are they?

AKC: Yes, they are. It’s almost like I feel like I’m drawing in blood. It’s just really coming directly out, and there’s a certain amount of pain in that. It’s sort of like George Grosz. You think he was laughing while he was drawing that grotesque stuff?It comes out of a dark place in me, definitely. When I paint, it doesn’t. My painting comes from a much lighter, more decorative, aesthetic side of me.

BLVR: What do you think it is about drawing?

AKC: It’s not drawing, it’s the writing. It’s raw because I’m writing about myself, and I’m revealing things to myself as I’m writing. You recall things that you’ve forgotten. It’s coming out in the line. So the drawing isn’t pretty or accurate; a lot of it has little to do with what reality looks like. It’s an emotional reality. It takes a lot out of you. I find I do it less and less. If I do stuff with Robert, like where we work together for the New Yorker, that’s kind of fun to do, because we’re just playing around. But some of that deeper, really painful stuff I drew earlier in my life was very difficult to do.

BLVR: I remember reading an interview with you where you said that the kind of aesthetic that you liked in comics is one where you can see the struggle.

AKC: Yes, exactly. That’s what moves me in people’s work. Other people are looking for work that’s kind of pyrotechnical and fabulously technically amazing in some way. Some people just want to be dazzled by the skill of the artist. But if there’s not an emotional engagement to me, I find it completely boring.

The artists I like are German Expressionist artists— you know, the kind of art where I feel that the person is really spilling it all out there. And all through history there have been artists in every period that were more like that than the others. Frida Kahlo’s paintings are more moving than Diego Rivera’s because they’re more personal. Some people have both, and they’re really lucky.